https://www.thedailybeast.com/cleopatra-napoleon-queen-victoria-and-a-vanderbilt-how-three-ancient-egyptian-obelisks-ended-up-halfway-across-the-world-in-new-york-city-paris-and-london

PHARAOH'S NEEDLES

Cleopatra, Napoleon, Queen Victoria and a Vanderbilt: How Three Ancient Egyptian Obelisks Ended Up Halfway Across the World

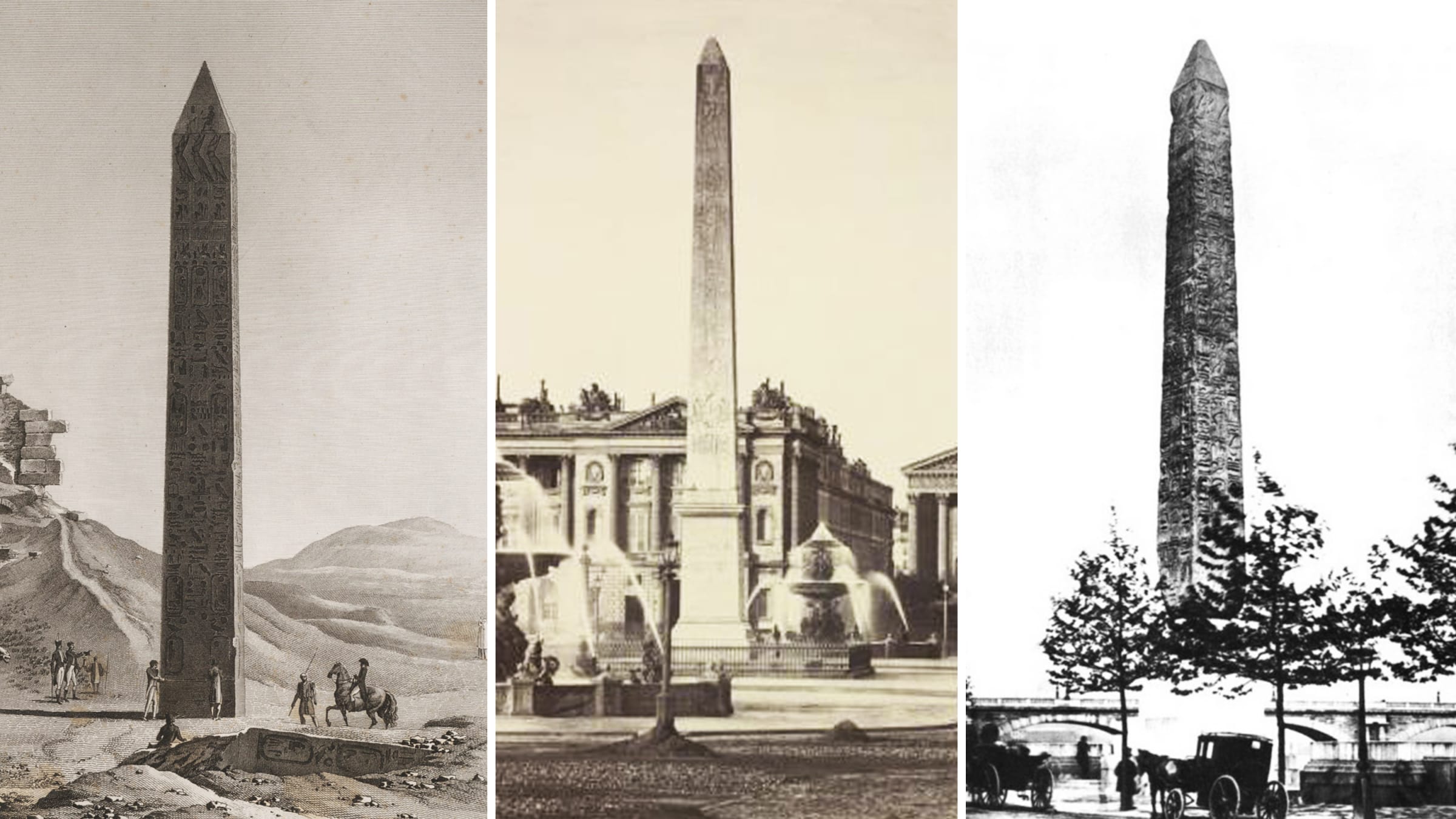

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast/Library of Congress/NYPL Collection

Looked upon by Cleopatra and Queen Victoria 19 centuries apart, lost at sea, and dragged through Manhattan: The incredible tale of the obelisks of Paris, NYC, and London.

03.30.19 11:00 PM ETIn the heart of Paris, just steps from the Grand Palais and the Louvre, there is a monument unique among the city's countless statues and memorials. A stone shaft 75 feet tall, the Luxor Obelisk stands at the center of Place de la Concorde, its gold pyramidal cap catching the light on sunny days. Etched on all sides are rows of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs commemorating the great works of the pharaohs. It is singularly out of place.

A similar obelisk stands on the north bank of the Thames in London, this one worn smooth in places by centuries of violence, and pockmarked by shrapnel from a World War I bomb. Its twin can be found across the Atlantic Ocean, hidden atop a knoll behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York's Central Park. In all three places, the obelisks are far older than the cities they stand in.

NYPL Collection

How did these obelisks come to be so far from home, out of place and context?

Each has borne witness to centuries of war and tumult. They have been toppled by earthquakes and burned by Persian armies. They have been shipped up the Nile, and lost in the sands of the Sahara. They were looked upon by Cleopatra and Queen Victoria 19 centuries apart. One was lost at sea. One was dragged through the streets of Manhattan.

The story of their removal from Egypt is a testament to the hubris of 19th-century European imperialism, tracing the arc of industrial and political advancement. It is a story of war and empire, of technological advancement and of cultural exchange. It is a story of art and architecture transcending time and place.

And it is a story which begins with Napoleon Bonaparte.

Years before he rose to rule France as emperor, Napoleon was a young upstart general fighting his way through Europe in defense of the young Republic's sovereignty. His plan was to smuggle an army across the Mediterranean into Egypt, which was then under Ottoman control, and push his way east into Syria. French control of this region would cripple Britain by cutting it off from its vast colonial holdings in India.

Napoleon arrived at the port of Alexandria on July 1, 1798, with some 25,000 soldiers. Though he enjoyed some early success, Napoleon retreated to France in 1799 and Egypt reverted to the British-backed Ottomans in 1801.

The victorious British troops sought a souvenir by which they might commemorate their triumph. On the shores of Alexandria harbor, they found an ideal candidate: there, buried in the sand and mud lay a 68-foot-long obelisk, the twin to the more famous "Cleopatra's Needle" which stood nearby.

Ancient Egyptians referred to obelisks as "tekhenu," which means "to pierce the sky." They were dedicated to the sun-god Ra and were "a symbolic representation of the sun's rays." The word "obelisk" originated centuries later, derived from the Greek word "obeliskos," which means a sharpened object, usually a spit for cooking over a fire.

Both Alexandrian obelisks were originally erected some time around 1400 BCE in Heliopolis, near modern-day Cairo. They ornamented what was then one of the greatest temple complexes of Egypt's New Kingdom, the period of dynastic stability which lasted from roughly 1570-1070 BCE. The temple and much of the rest of Heliopolis was destroyed in 525 BCE by an invading Persian army, and the obelisks were toppled to the ground.

They remained prostrate where they fell until the first century BCE, when they were hauled to Alexandria for use in the "Caesareum," a temple dedicated to the Caesars. There they would have presided over all the violence and intrigue of six centuries of Roman rule: Egypt's pharaonic line came to a dramatic end with Cleopatra's suicide in 30 BCE.

Christianity gained traction in Roman Egypt, with Alexandria emerging as a center of religious activity. The Caesareum was converted into a Christian church in the third century CE. It was there, in the shadows of the obelisks, that the pagan philosopher Hypatia was beaten to death and burned by a Christian mob in 415 CE.

Alexandria remained under Roman rule until 646 CE, when it and the rest of Egypt fell to Arab invaders. The city went into decline as nearby port cities like Rosetta grew in prominence. The obelisks remained standing together until a great earthquake in 1303 CE knocked one to the ground. It rested there, mired in the shoreline muck, for the next 500 years.

The remaining obelisk became a landmark for the city, known colloquially as "Cleopatra's Needle." The fact that the it was likely not erected at the Caesareum until several years after her death mattered little. Through the lens of romanticized history, Queen Cleopatra and the lonely harbor obelisk each symbolized Alexandria's ancient Egyptian heritage. Calling the obelisk "Cleopatra's Needle" helped tie the city to its long-lost glory days.

Plans were drawn up by the British to haul the fallen obelisk home to London as a spoil of their victory. A sunken French frigate was raised from the bay to act as a pier by which the stone might be pushed into a British ship for transport, but a storm arose and washed the frigate away. The British fleet left shortly thereafter, abandoning the obelisk where it lay.

Over the next two decades, Britain then attempted to secure the obelisk as a gift of friendship from the Egyptian government. A letter written in 1820 by Samuel Briggs, British Consul at Alexandria, stated that it was to be "unique of its kind in England, and might, therefore, be considered a valuable addition to the embellishments designed for the British metropolis."

The obelisk was gifted to Britain, but no funds were allocated for its removal. The landowner where it sat threatened to cut it up for use in construction. Still, despite various attempts and creative machinations over the ensuing decades, the British-owned obelisk continued to wait in the mud in Alexandria.

Not to be outdone, the French negotiated the acquisition of the other obelisk, Cleopatra's Needle, in 1820. They too then all but abandoned their gift for lack of funds and a workable plan for how to remove it from Egypt. It continued to bestride Alexandria harbor, as it had for centuries.

In 1829, the renowned scholar Jean-Francois Champollion (who is credited with deciphering hieroglyphics for the first time) wrote to French authorities of a superior pair of obelisks at a temple in Luxor. He strongly suggested that they be secured for France, even if it meant relinquishing their claim to Cleopatra's Needle in Alexandria. He felt that, despite being less famous, they were far more valuable artistic and archaeological specimens.

On Nov. 29, 1830, the Khedive (viceroy) of Egypt Muhammad Ali Pacha ceded ownership of all three obelisks as a display of "his gratitude to France for the numerous marks of kindness and friendship that have been manifested to him at different times." An immense wooden transport barge named the Louqsor was assembled at Toulon, on France's Mediterranean coast, and dropped anchor in Alexandria harbor on May 3. Its crew transferred to a flotilla of smaller river boats and entered the Nile at Rosetta, bound for Luxor.

They arrived a month later, bearing witness to what Champollion had described as "the city of a hundred gates, containing palaces, sphinxes, and colossal monuments, all bearing witness to a past grandeur and subsequent decadence."

Luxor in the 1830s was a century away from being an international tourist destination. The sailors found a sleepy farming village filled with half-buried temples and monuments. Some 30 homes would need to be demolished in order for the French workers to lower the obelisk and drag it to the river. After a cacophonous negotiation orchestrated by a government translator named Ibrahim, a settlement was reached whereby each property owner was compensated. Ibrahim, it was later discovered, received a substantial kickback for his role in the mediation.

Around 400 local men, women, and children were employed in the demolition of the houses and subsequent dredging of a canal which would allow the Louqsor to pull perpendicular to shore for easier loading of its ancient cargo. Awestruck locals, most of whom had never seen such a great ship before, compared it to a "floating mosque" as it was maneuvered into position.

The French elected to take the western obelisk, closest to the river, for the obvious reason that it would be easier to haul away than its twin. The 75-foot-tall, 200-ton stone was encased in wood in preparation for lowering, but an outbreak of cholera killed off many local laborers, along with several Frenchmen. Delayed but undeterred, the crew finished work on a complex set of pulleys which would disperse the weight and stress of the lowering monolith, allowing it to fall gently onto a trackbed which had been constructed to carry it down to the Louqsor.

On the morning of Oct. 24, 1831, nearly five months after the crew had disembarked at Luxor, everything was finally in place. The command was given, and the obelisk was lowered in stages. Slowly and with great difficulty, the immense stone was brought to horizontal and dragged toward the waiting ship. It was finally aboard on Dec. 19: "The joy and pride felt by all […] at the completion of that important operation may be imagined more easily than described; four months and a half of excessive toil, trial, and suffering were rewarded by complete success."

The crew then waited eight weary months in Luxor for the Nile to rise high enough to float the heavily laden ship so they could sail north. It departed on Aug. 25 and reached Rosetta, on Oct. 1, where they became trapped for another three months by low water. Finally out of the Nile, the ship proceeded to Alexandria, where it was trapped by bad weather until April. At last, the Louqsor reached the port of Toulon on the night of May 10, 1833. There, they were quarantined for another month.

The ship reached Paris that December, but had to wait until the following August for the flow of the Seine to become low and gentle enough for the obelisk to be unloaded. After all that time and effort, when it finally reached its new home at the Place de la Concorde, no pedestal had been prepared for it.

A 236-ton block was hauled from Brittany to be carved. At last, on Oct. 25, 1836, the Luxor Obelisk was hoisted into place using a reverse implementation of the same methods employed to lower it from its former home in Egypt. US Navy Admiral Seaton Schroeder pointed out that the obelisk had been "brought from the silent ruins of the greatest city of the ancient world, to the brightest and gayest of modern capitals." It stood precisely where King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette had been executed just 43 years prior.

Despite officially owning both obelisks at Luxor, France never sought to retrieve the twin to the one erected in Paris. Nor did they ever attempt to fetch Cleopatra's Needle in Alexandria. It seems they were quite satisfied with the experience of having transported one ancient 200-ton monolith across the sea. No need for any more.

Across the channel in England, debate continued over Britain's obelisk, which was now being incorrectly referred to as "Cleopatra's Needle." One proposal after another was presented to Parliament but collapsed over financing. Meanwhile in Egypt, souvenir hunters chipped away at it, finding its vulnerable state on the ground too tempting to resist. One hammer-wielding British traveler caught breaking off a piece of its hieroglyphics in 1859 stated that he knew it belonged to Britain, "and as one of the British nation I mean to have my share."

While in Paris in 1867, a British Lieutenant-General by the name of Sir James E. Alexander was struck by the sight of that city's magnificent Egyptian monument in Place de la Concorde. Seeing it, he was reminded of Britain's neglected obelisk in Alexandria and set out on a concerted effort to rectify the situation.

For the next eight years, he worked on the finances and logistics of the project. Dozens of ideas were handed down as to how the obelisk might be safely transported to London. Much technological progress had been made in the decades since France had acquired their obelisk by way of a wooden barge. Shipbuilding was revolutionized in the 1840s by the introduction of wrought iron hulls, and Britain was keen to show off its industrial might wherever possible. Thus it was decided that the obelisk could be encased in a giant iron tube, which would then be dragged to England by a larger ship.

When workers finally arrived on-site in Alexandria in the first half of 1877, to begin excavating the partially buried obelisk, they were significantly delayed by the owner of the land, who demanded restitution from the government for allowing it to encumber his property for so many years. He was finally placated by a satisfactory settlement, and work could begin in earnest.

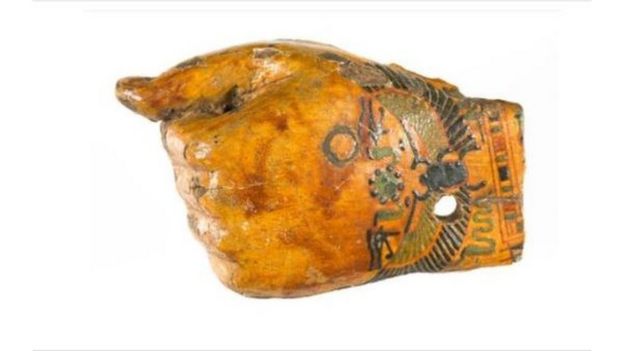

Earth was removed from around and beneath the obelisk, with wooden blocks inserted to support it as excavation progressed. Dozens of artifacts were discovered, including a burial vault containing multiple skeletons, the skulls of which were kept as talismans by the sailors.

On the whole, the British had a much simpler task at hand than the French had half a century prior, simply by virtue of having their obelisk already lying horizontal, ready for shipment. There was no need for a complex system of ropes, winches, and pulleys like those used at Luxor. They merely had to excavate, pack, and sail.

Once the obelisk was freed from the ground, the iron tube was built around it, piece riveted to iron piece, until it was fully enclosed. Fully built, it was 92 feet long with a diameter of 16 feet. The obelisk was suspended within it by a series of iron ribs. It was outfitted with a rudder and sails to help stabilize it during the journey across the sea, and with a small cabin to house the crew.

On the foggy morning of Aug. 28, 1877, two steam-powered tugboats were chained to the tube, which had been christened the Cleopatra, and attempted to pull it out to sea. It inexplicably began to take on water, and divers discovered that a stone hidden in the sand had pierced its hull. The tube had to be rolled upside-down for repairs before its journey could finally get underway.

Led by Captain Henry Carter, the Cleopatra was towed out of Alexandria harbor on Sept. 21 by the steamship Olga, making stops at Algiers and Gibraltar on its way toward its new home. It rounded the southwestern coast of Portugal on Oct. 10, but encountered a terrible storm four days later off the northwest coast of Spain. The vessels were thrashed violently and six sailors were swept to their deaths before Captain Carter called for the Cleopatra and its precious cargo to be cut loose from the Olga. It was considered lost to the angry sea.

The New York Times was amused to speculate on "the wonder and bewilderment of future archaeologists who should find the monolith" thousands of years later. What would they think, the newspaper continued, when they not only found the obelisk so incongruously "in the midst of a submarine deposit," but also "encased in a metal tube to protect it, apparently, from the elements."

But the obelisk did not sink, and was soon recovered by a Scottish steamer named the Fitzmaurice, which found the Cleopatra adrift and towed it into port at Ferrol, Spain. (The skulls that had been taken on at Luxor were nowhere to be found, presumably tossed overboard during the storm by superstitious Maltese sailors.) There it sat for three months as the captain of the Fitzmaurice fought for a salvage bounty. It was finally retrieved by the tugboat Anglia and reached London on Jan. 20, 1878.

A number of locations were proposed as the obelisk's final resting place. The preferred spot was in the center of what is now known as Parliament Square Garden, just north of Westminster Abbey. City officials even went to the trouble of erecting a wooden mockup of the obelisk on the site to see how it would look.

The problem with this location, however, was that it would have situated the 200-ton stone (plus its pedestal) directly above the tunnels of the Metropolitan Underground Railway. The company's owners demanded permanent indemnity against the possibility of it falling through the earth onto their tracks. City officials opted to relocate the obelisk instead.

In the end, a site was chosen along the banks of the Thames just east of the Charing Cross rail bridge. There, the Cleopatra was nestled into a timber cradle and, at low tide, dismantled to expose the obelisk within. Using hydraulic jacks, it was lifted up onto the embankment. An iron sleeve was slipped around the obelisk, equipped with arms which would allow it to be brought upright into position.

Its pedestal, unlike that of Paris, was ready and waiting. Sealed within it were an assortment of mementos: a complete set of British coinage (including an Indian Rupee), a vellum-printed description of the obelisk's acquisition and journey out of Egypt, a map of London, a railway guide, a Hebrew Torah, Bibles in multiple languages, some children's toys, a box of cigars, and "photographs of a dozen pretty Englishwomen" from none other than Captain Carter of the Cleopatra.

On Sept. 12, 1878, the obelisk was at last hoisted vertical above its waiting plinth before an approving crowd. The Union Jack and an Ottoman Turkish flag were raised in celebration. The next day, their so-called "Cleopatra's Needle" was lowered into position and its supports removed. In 1881, bronze wings were added to its base to camouflage its damaged edges, and a pair of bronze sphinxes were added to either side of it to complete the decorative array.

As early as September 1877, while London's obelisk was being towed out of Alexandria harbor, work was afoot to secure a similar trophy for the United States. Eager to cement its status as a global power, as equal an heir to the ancient empires of the East as any of her European brethren, the United States viewed the acquisition of an obelisk as vital to the development of its global reputation.

From the New York Herald: "It would be absurd for the people of any great city to hope to be happy without an Egyptian Obelisk. Rome has had them this great while and so has Constantinople. Paris has one. London has one. If New York was without one, all those great sites might point the finger of scorn at us and intimate that we could never rise to any real moral grandeur until we had our obelisk."

A flurry of letters were exchanged over the course of several months in early 1879 before word was handed down that the Egyptian Khedive Ismail Pasha had agreed to give the famous Cleopatra's Needle of Alexandria as a gift of friendship to the United States.

The American Consul-General in Egypt, Elbert Farman, wrote to Washington at the conclusion of the negotiations: "The gift of this ancient and well-known monument cannot be regarded as other than a very great mark of favor on the part of the government of Egypt toward that of the United States, and proof of its high appreciation of the friendship that has ever existed between these countries."

It was more than international camaraderie which convinced Ismail Pasha to grant Cleopatra's Needle to the Americans, however. By the time he made this agreement in early 1879, Britain and France were pressuring the Ottoman government to overthrow him as Khedive, fearing that he was too independence-minded. (Ismail hoped his gift would keep the United States neutral in this tug-of-war over his leadership. He was deposed that June and replaced by his more compliant son, Tewfik.)

Unlike the obelisks taken by France and Britain, the one claimed by the United States was a beloved and internationally recognized landmark of Alexandria, where it had stood for more than 18 centuries as a symbol of the city. Residents were aware that it had been "given" to the Americans, but never expected them to show up to retrieve it so soon, as they did on Oct. 16, 1879.

Alexandrians were whipped into a frenzy of shock and indignation at the idea of their obelisk being taken away so quickly. Vitriolic articles appeared in local newspapers and physical violence was threatened against workmen at the site. The resistance extended to European politicians and resident archaeologists, who insisted that it was illegal to remove historic objects from Egypt, despite the Khedive's declaration and their own predations.

In response to these hurdles, the American excavation teams doubled their efforts, working night and day to erect the scaffolding and pits necessary to lower the obelisk from its plinth and carry it to the harbor. The British hadn't had to lower their obelisk, so the Americans had only the French at Luxor half a century prior for instruction as to how to safely bring theirs down from its pedestal.

Like the French, the Americans erected an enormous lever and pulley system, and with some difficulty, Cleopatra's Needle was brought to horizontal on Dec. 6. The watching crowd, which had been hostile and unruly at first, grew deathly silent as the stone began to move, and cheered when the feat was accomplished. It took three more months for the obelisk to be lowered onto a wooden track which would allow it to be pushed to the water for transport.

Taking a lesson from the British, who had almost lost their obelisk at sea, the Americans procured a decommissioned Egyptian mail freighter which was large enough to take Cleopatra's Needle directly into its hold for the long journey across the Atlantic. The ship in question, the Dessoug, had a hole cut in its bow and the obelisk was slid into it using a floating dock. Its 50-ton pedestal followed suit, resting atop a steel mount in the ship's stern.

In June of 1880, the American crew traveled to Cairo to bid farewell to the Khedive, thanking him for resisting European and Alexandrian calls to revoke the gift. At last, on June 12, the Dessoug raised anchor and sailed out of Alexandria harbor, bound for New York.

The ship passed uneventfully through Gibraltar and the Azores, but its engines broke down abruptly in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean on July 6. It limped along on the power of its sails for a week while its crew made repairs. During this time, they intercepted and purchased bread from a passing Austrian ship en route to Constantinople. The Dessoug was at last repaired and reached New York on July 20, anchoring in the Hudson River off 23rd Street.

On arrival, the crew of the Dessoug found that the city was still debating where exactly Cleopatra's Needle should stand. City officials argued on behalf of placing it in the plazas on either 5th or 8th Avenues and 59th Street, at the corners of Central Park. These sites would be highly visible and easily accessible to all New Yorkers, but there was concern that the eventual buildup of high-rises around it would detract from the obelisk.

William H Vanderbilt, whose money had funded the majority of the obelisk's journey out of Egypt, pressed for it to be placed on a knoll near the newly constructed Metropolitan Museum of Art in Central Park. In the end, his opinion won out and the obscure hilltop was readied for its new occupant.

The Dessoug sailed south to Staten Island, where its hull was reopened and Cleopatra's Needle at long last emerged into the New York sun. It was then transferred to a set of pontoons and floated across the harbor to the dock at Manhattan's West 96th Street. There, the first major hurdle was to get the obelisk across the heavily used riverfront tracks of the New York Central Railroad.

To block rail traffic with the obelisk for any length of time was out of the question, so a temporary bridge was constructed and thrown across the tracks between passing trains. As quickly as they could, workers dragged the 77-foot-long, 240-ton obelisk across the tracks and removed the bridge, allowing train traffic to resume. The whole endeavor took just 80 minutes.

Using a system of wooden trestles, the obelisk was dragged through the city, first along 96th Street to Broadway, then south to 86th Street. There, it was once again turned and made its way into Central Park. Drastic elevation changes made crossing the park grueling work.

On Jan. 5, 1881, after multiple delays due to snow and cold weather, Cleopatra's Needle arrived at its hilltop destination. The journey from the river had taken 112 days at an average pace of 97 feet per day.

As in London, a time capsule was buried in the foundation of Cleopatra's Needle in New York, containing coins, medals, and a copy of the Declaration of Independence. The obelisk's original granite pedestal was dropped into position via horse-drawn wagon, and the stage was set for the monument to finally be turned upright once more.

A crowd of some ten thousand flocked into Central Park on Jan. 22, 1881, to watch Cleopatra's Needle being brought to vertical. A silence which was, according to one contemporary witness, "almost unnatural" gripped the audience until the obelisk reached the 45-degree mark, at which point it was halted for a photo. When it resumed its upward motion, a roar of excitement rippled through the gathering

"It is something," exclaimed Henry H. Gorringe, "to have witnessed the manipulation of a mass weighing nearly 220 tons changing its position majestically, yet as easily and steadily as if it were without weight." After 15 months of journeying across more than 5,000 miles, the obelisk was turned upright in just five minutes.

New York's was the last obelisk to be taken out of Egypt. Its status as a major tourist attraction faded over time, and today it is obscured from view by the southern wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. London's obelisk was nearly destroyed in 1917 when a German bomb detonated nearby in an air raid during World War I. The Luxor Obelisk in Paris, meanwhile, finds itself standing at the center of a traffic circle better remembered as the site of royal beheadings than as the home of an Egyptian masterpiece.

In the end, all three obelisks are too far from home and too out of context to be truly appreciated. The average tourist or commuter will likely never know the magnitude of their age or what they endured to end up in their present locations. By removing the obelisks from Egypt, these cities have stripped them of their meaning, turning them into just one of many baubles meant to decorate the imperial capitals of the modern age.

Across the sea in Luxor, on the wide bend of the Nile which defines southern Egypt, stand the ruins of Luxor Temple, now a popular first stop for tourists on their way to the Valley of the Kings or Karnak. Flanking its entrance, are two colossal statues depicting a seated Rameses II wearing the dual crown of a united Upper and Lower Egypt. Towering over the left statue is a tapered granite obelisk set atop a plinth depicting rows of baboons. Before the right statue lie the remains of a similar plinth, but without its obelisk.

The mismatch gives the temple an uneven appearance, its symmetry undermined by the absence of so integral a piece of its outer ornamentation. The knowledge that this missing obelisk now stands a world away in the center of Paris seems beyond comprehension. It seems almost grotesque.

Former US Secretary of State William Evarts summed up the pillaging best when he declared in 1881, "These obelisks, great and triumphant structures, […] mark a culmination of the power and glory of Egypt, and every conqueror has seemed to think that the final trophy of Egypt's subjection and the proud pre-eminence of his own nation could be shown only by taking an obelisk—the chief mark of Egyptian pomp and pride—to grace the capital of the conquering nation."

-- Sent from my Linux system.