An empire that spanned 3,000 years, from 3100 BCE to 332 CE, ancient Egypt amassed enormous wealth thanks to its rich agricultural lands and abundance of minerals such as gold, granite and, turquoise. Protected from invasions by the area's unique geography of desert, coastline, and Nile river floods, the region also benefitted from relative political stability—especially when compared to neighboring regions where warlording was fierce and ongoing.

Wealth and stability in ancient Egypt allowed for specialized education to flourish, especially medicine. Egyptian doctors—both men and possibly women—were the best in the ancient world and highly sought after by foreign kings and queens. Even as Egypt's political power faded, scholars say medical knowledge flowed up from Alexandria into the bourgeoning empires of Greece and Rome, and not the other way around.

Ancient Egyptian remedies included things like honey, crushed insects, opium, and also cannabis, according to some scholars (but not all). Archeologists think a woman's role in medicine was mostly relegated to gynecology and obstetrics, with medical treatments listed in ancient scrolls that include cannabis. In the late antique era, many more women functioned as professional practitioners of magic and spells. Could cannabis have been among the common herbs used in their rituals?

Was cannabis used in ancient Egypt?

Whether through human activity or blown in with the desert sands, cannabis pollen was found in the tomb of Ramses II, circa 1200 BCE, along with two additional soil samples from pre-dynastic periods (prior to 3200 BCE). While archaeologists maintain there is weak physical evidence of cannabis use in ancient Egypt, there are written references to a plant some scholars are confident was indeed cannabis.

In 2350 BCE, the Pyramid Texts from the Old Kingdom were carved into stone. On these stone tablets is the hieroglyphic symbol smsm.t—or "shemshemet"—which references "a plant from which ropes are made." Archeologist W.R. Dawson argued in a 1934 edition of The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology that this is a reference to hemp. Not all scholars today agree, but many accept that shemshemet refers to cannabis, as it's also written in medicinal contexts on ancient scrolls, called papyri.

Whether or not ancient Egyptians used cannabis for its euphoric qualities is also debated by archeologists—"let's get high!" was not explicitly written down by ancient scribes. However, medicine and magic were inextricably linked in the ancient world: ritual fumigations accompanied by spells and incantations were as much a part of medicine as diagnostics.

Could cannabis have been used in fumigations for the unwell, spiritually compromised, or to rouse the gods? There is no hard proof, but it's possible.

Women, medicine, and magic

Women in ancient Egypt had full rights under the law and enjoyed more freedoms than their contemporaries in neighboring lands. They held property, personal wealth, and ran their own businesses. While peasant girls (and boys) weren't typically educated, daughters from wealthier households were privately schooled alongside their brothers.

In the medical field, midwifery was largely the domain of women, while it's thought mostly men became physicians. In Women of Ancient Egypt (2013), Egyptologist Barbara Watterson writes of a school of midwifery at the Temple of Neith (goddess of creation) in the city of Sais.

A school thought to have trained women, one can speculate Agnodice of Athens went here to learn. As the legend goes, Agnodice, from the 4th century CE, went south to Egypt for medical training after being denied it in her native Greece. Upon her return to Athens, disguised as a man, she was so good at her job that jealous Greek doctors accused her of seducing patients and put her on trial.

In addition to obstetrics, midwifery students learned of herbs, spells, incantations and special amulets to protect mothers and newborns from malevolent spirits. Writes Watterson: "The earliest 'doctor' was a magician, for the Egyptians believed that disease and sickness were caused by an evil force entering the body."It wasn't just educated women that deployed herbaceous healing spells—or curses. From the late antique era, between 250 and 750 CE, multiple manuscripts have been found for common folk containing magic recipes. Listing things like "wild herbs, froth from the mouth of a black horse, and a bat," these spells were drawn up and carried out by professional herbalists and healers who were often old women.

Because we know Greek and Roman doctors were writing about cannabis in the same time period, and the plant had long been used in neighboring Syria and Mesopotamia, it's easy to speculate cannabis was also included in these laypeople's spells for love, luck, health, and revenge. The Coptic Magical Papyri Project is currently collecting hundreds of these recovered manuscripts on magic in an attempt to decode and organize them all, with a projected completion date of 2023.

Seshat: Goddess of medicine, learning, and cannabis

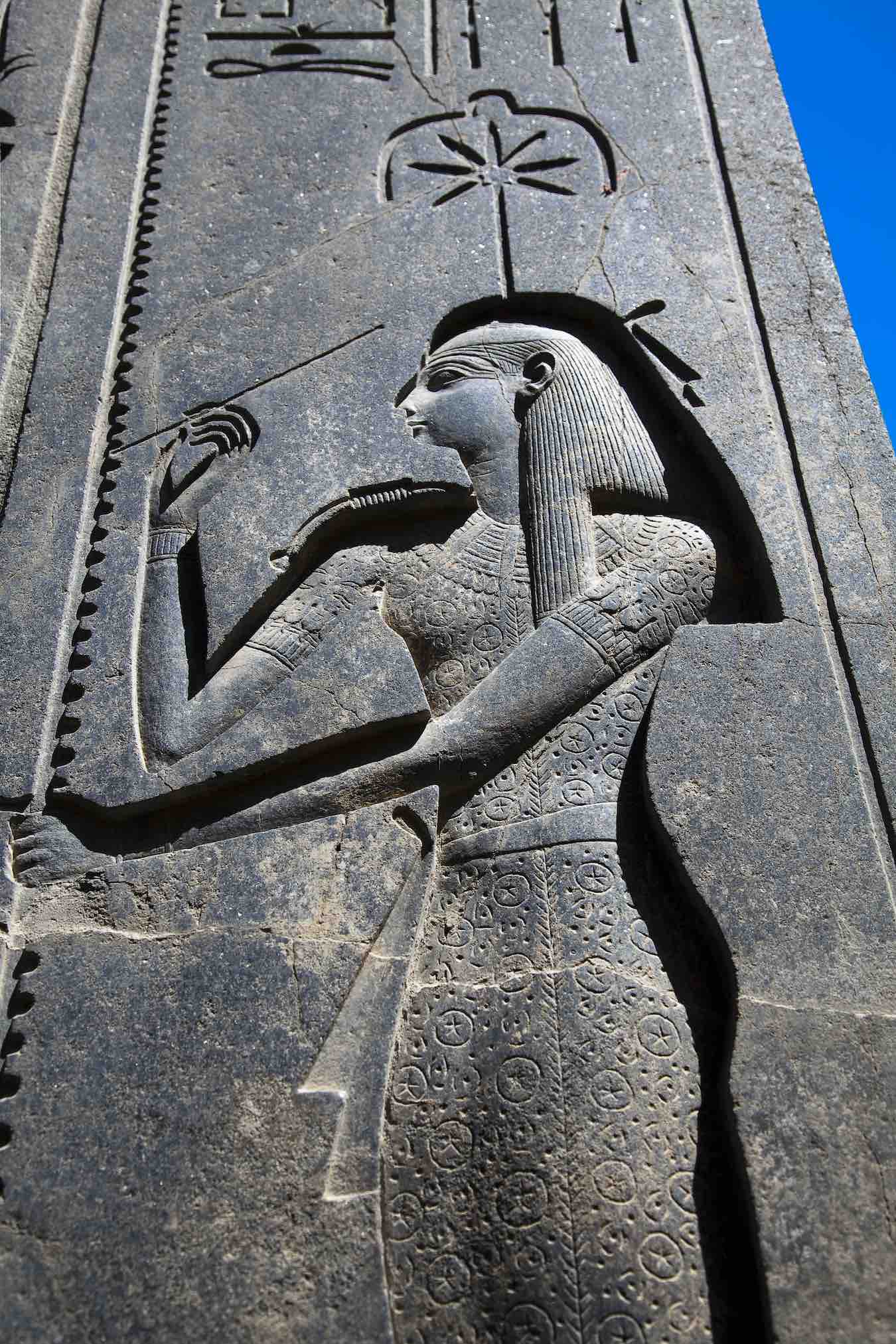

The goddess Seshat, with her seven-pointed-star headdress. (Bradhenge/AdobeStock)

We can't talk about ancient Egypt, medicine, magic and cannabis without mentioning goddess Seshat or Seshet: patroness of scribes, mistress of builders, goddess of the House of Life—a term to include all medical schools.

Seshat's headdress, a seven-pointed star, bears a striking resemblance to cannabis. It was thought that when mortal scribes committed words to paper, Seshat received a copy and catalogued it with the gods. When temples were built, rituals in honour of Seshat included "stretching of the cord" which some scholars say was hempen rope.

It was uncommon for a female deity to preside over men, making Seshat a curious choice to officiate medical schools. Because we know that writing things down in ancient times was expensive, time-consuming, and mostly reflected the interests of those who could afford scribes (i.e., men of influence), it's possible more women were active in medicine, magic, and the healing arts than what was recorded a few thousand years ago.

What is clear is ancient Egyptian elites placed immense value in writing down diagnostics and medico-magical treatments, which could have been used by anyone trained to read, male or female.

A timeline of ancient medical cannabis use

If we follow that shemshemet is cannabis, there are a number of applications cited by ancient papyri that make sense today, given modern cannabis' track record of easing pain, nausea, and anxiety. Here's what's been found so far:

1880 BCE: The Kahun Papyrus is considered the first textbook on gynecology and believed to be a copy of a much older document. While it doesn't mention shemshemet directly, it does include fumigation, suppositories, edible medicines, and massages made from plant, animal, and mineral matter for almost all maladies of the uterus.

1700 BCE: According to ethnobotanist Ethan Russo, the Papyrus Ramesseum III has the earliest mention of cannabis as an eye treatment: "celery, hemp, is ground and left in the dew overnight. Both eyes of the patient are to be washed with it early in the morning."

1500 BCE: A complete medical tome, the Ebers Papyrus is 65 feet (20 meters) long, listing hundreds of spells and remedies. Shemshemet is mentioned:

- To "cool the uterus": shemshemet is ground in honey and used as a vaginal suppository. Whether this was for laboring women, menstruation, or a different gynecological issue is unclear.

- To dress a painful toenail, shemshemet was mixed with honey, ochre, and other herbs as a poultice. (Many Egyptians worked barefoot in flooded agricultural fields, making infected toenails a common problem.)

1300 BCE: The Berlin Papyrus offers a treatment for aaa, thought to be schistosomiasis, or fluke worms, which enter the bloodstream via the soles of the foot. Driving away aaa included fumigating the patient with a combination of shemshemet, ground up insects, and grains. Another passage mentions cannabis made into an ointment for fever.

1200 BCE: The Chester Beatty Papyrus offers a rectal suppository made of shemshemet, goose fat, and acacia leaves to treat diarrhea (likely cholera). Another prescription for headaches is said to include cannabis.

800 BCE: In the Greek epic The Odyssey, Helen of Troy sprinkles into wine "a drug that can lull all pain and anger," a remedy shown to her by an Egyptian woman. Called "nepenthe," some scholars say the drug in question was opium, while others argue the effects described in the story are closer to cannabis.

In the first century CE, Greek historian Diodorus Siculus documented Egyptian women using nepenthic potions reminiscent of Homer's Odyssey. Egyptian wine vessels excavated from the Coptic era (third and fourth centuries CE) also contain traces of cannabis, making it plausible nepenthes were cannabis-based.

100-200 CE: Ethan Russo offers that the word for cannabis changed to msˆy during these centuries. A papyrus from this time mentions treating abscesses with cannabis poultices, and tumors with cannabis heated along with minerals and other plants. "The latter passage is particularly interesting in its specification for heated cannabis, suggesting decarboxylation of phytocannabinoid precursors might have been operative," he wrote.

Egyptology is an evolving science. The painstaking academic care used today to uncover and classify artifacts, along with technologies that can back up educated guesses, were not in place when Western archaeologists lifted ancient objects from their resting places in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

As such, what has been written (in the West at least) about ancient Egypt can be refuted in the future with a new discovery or by re-evaluating old assumptions with a fresh perspective. The controversy surrounding ancient Egyptian use of cannabis, and medical women who wielded the herb, may not be inconclusive forever.

-- Sent from my Linux system.