https://www.townandcountrymag.com/leisure/travel-guide/a26414973/egypt-tourism-2019-print/

Can Egypt Convince the World That It Is Starting Over?

The world's oldest civilization faces challenges from the past, present, and future. But an ambitious new cultural agenda has it ready for the here and now.

In the middle of Cairo's sprawl lies the City of the Dead, a dense, two-mile-long grid of tombs and mausoleums that dates back to the conquest of Egypt in AD 642 by Arab Muslims, when their commander, Amr Ibn al-As, established his family's graveyard at the foot of the Mokkatam Hills. As it grew, al-Qarafa ("the cemetery") acquired a population of the living, who transformed old funerary structures to suit their needs in the here and now. Today it is home to some 500,000 people, the poorest of the poor. I lived in Cairo as a child for two years and have traveled there repeatedly since; going to the City of the Dead never seemed like a good idea.

But on the afternoon of my arrival last October in the city, which is now home to 20 million people, Mounir Neamatalla, a well-connected man about town, founder of the investment and consulting firm Environmental Quality International (EQI) and champion of his country's many aspects, calls to give me a heads-up: "There's an event in the City of the Dead tonight that you might want to see." He didn't say much more. "You don't want to go there," the driver who picks me up at the airport insists, hearing of my plans. "You go there only if you're visiting a dead body, burying a dead body, or buying hashish."

I'm doing none of the above. I'm in Cairo because, after eight years of political turmoil here, there is a new wave of cultural development, one that may herald a fresh chapter for Egypt and, along the way, update the classic itinerary embraced by so many visitors to the country. Two new museums, long in the planning but delayed since the 2011 revolution by lapses in funding and lack of political will, are finally getting ready to open: the Grand Egyptian Museum, the showstopper near the pyramids of Giza; and the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, in the Fustat district of Old Cairo.

At the same time, the city's most storied cultural institution, the pink Beaux-Arts Egyptian Museum on Tahrir Square, downtown, is getting a long-overdue restoration; since 1902 the museum has been synonymous with Egyptian antiquities, but it has occasionally been something of a laughingstock because of its inability to properly take care of them.

And then there's the rest of downtown Cairo. Once dubbed "Paris on the Nile," it started falling into disrepair in the 1950s, but it is now being slowly revitalized, building by gorgeous building. Many were commissioned in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, during the Europeanizing, modernizing Khedive dynasty, a period that is still referred to by Egypt's cosmopolitan elite as the country's Renaissance, its "glory years."

We arrive late at the City of the Dead because I refuse to forgo my first-night-in-Egypt tradition—a sunset felucca sail on the Nile—and because we get stuck in one of Cairo's spectacular traffic jams. ("There's someone dead and a funeral," our driver informs us as we draw near, not clarifying things one bit.)

The event turns out to be a bustling celebration of the restoration of one of the cemetery's most beautiful funerary complexes: the mosque and mausoleum built in 1474 by Sultan Al-Ashraf Qaitbay, of the Mamluk dynasty. Hip Cairenes mingle with expats and a few City of the Dead locals in a small, theatrically illuminated square. There's an outdoor modern dance performance and a riveting talk in one of the mausoleum's reception halls about historic restoration. (Conducted in this instance by the Cairo-based Polish architectural firm Archinos, under the auspices of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities and with European Union funding.)

A Cairo Who's Who

Tarek Tawfik: Director general of the Grand Egyptian Museum

A former professor with a pharaonic new task. "My hope is that GEM will invite us all to think about our role in history—that even big old civilizations perished—so that we act more sanely and cautiously."

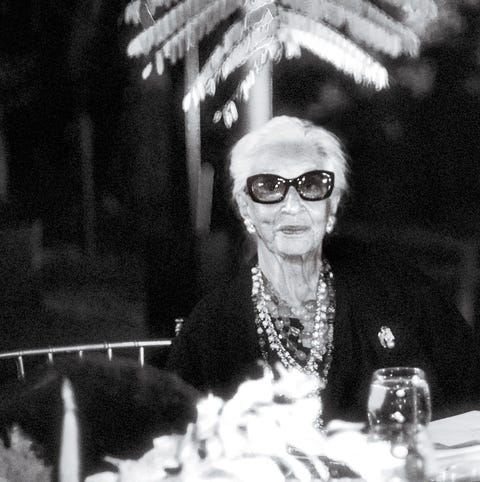

Lea Boutros-Ghali: Egypt's elegant grande dame

The widow of former UN secretary-general Boutros Boutros-Ghali, she is a symbol of a sophisticated, worldly Egypt with broadly humanistic values. "In order to be a good Muslim, you have to recognize Judaism and Christianity."

Zahi Hawass: Archaeologist extraordinaire

The Indiana Jones–like former minister of antiquities is excavating again: "I feel there is something behind that mountain in the Valley of the Kings. If we find what I'm looking for, I think it will turn the world around."

Khaled El-Anany: Minister of antiquities

He is charged with unearthing, preserving, and promoting Egypt's treasures. "My wish is for 10 times the tourists we have now. Americans are still nervous about Egypt and the whole region. It's a critical period. I would love to study it one day."

Nadine Abdel Ghaffar: Founder, Art d'Egypte

Daughter of a Coptic mother and a Muslim father and organizer of contemporary art exhibits, she is one of her country's great boosters. "The past still lives on here in a way, which is the charm of Egypt. You actually feel as if you're in a movie."

Neighborhood artisans have set up stands to showcase their wares and benefit from the influx of visitors. Several chauffeured black cars idle on the periphery. I don't spot a police or security presence—those guys are usually visibly packing beneath their suits—but I don't mind. A full moon floats above the elegant minaret of Qaitbay's mosque (the sultan is reputed to have been a sophisticated patron of architecture), and I sense the onset of that mysterious euphoria that generally befalls me in Egypt: the at-oneness of the past, present, and future.

"This area is like Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn back in the day," says Neamatalla, who spent time in the 1980s in New York, studying at Columbia University. "I wanted you to get a sense, even here, of Egypt's potential."

The State of Affairs

The stability that might actualize that potential is still somewhat delicate in Egypt, whose recent history has been, to say the least, eventful: the revolution that marked the end of Hosni Mubarak's 30-year regime (2011), the ascension to power of the Muslim Brotherhood and the election of the Islamist Mohamed Morsi (2012), a popular anti-Islamist uprising supported by a military coup (2013), and the election to the presidency of field marshal Abdel Fattah el-Sisi (2014).

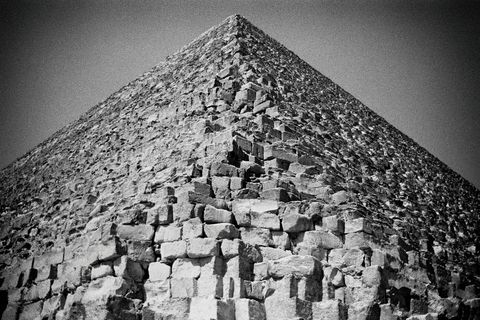

Also, in Egypt stability can hardly be confused with democracy. Last May, Sisi won his second presidential "election" with 97 percent of the vote. ("He's settled in like a god, a pharaoh," quips Wageeh Wahba, a columnist for the liberal-leaning newspaper Al-Masry Al-Youm, which translates as The Egyptian Today.) And it does not mean the end of the terrorist threat. Sisi promised to secure Egypt from the aggressions of political Islam (Islam not as religion but as the political exploitation of religion). Despite the roadside bomb incident near the pyramids of Giza last December, he has by now largely confined Isis and other radical groups to the North Sinai, near the border with Gaza, and the Western Desert, toward Libya, which are both now no-go zones for tourism. (They are also far from where most Egyptians live.) And he has done so with unabashedly autocratic tactics.

In the cities, you might not be able to recognize the security details (as I probably didn't in the City of the Dead), but they are omnipresent. During a walking tour of the renovated buildings of downtown, I try to take a photo of the restored Sha'ar Hashamayim (Gate of Heaven) synagogue, on Adly Street, built in 1905—and am instantly surrounded. "No pictures, madame. For security."

"My ministry is getting money it never got before," Khaled el-Anany, Egypt's dynamic, fast-talking minister of antiquities, tells me when I ask about the renewed fervor that is also apparent on the archaeological front, which is yielding new discoveries at an unprecedented rate. "We are working everywhere. There's a big political push from the president, who has decided that preserving our heritage is a priority. We know that our antiquities are our soft power, the best message Egypt can send the world."

"We are on the cusp of a re-renaissance," says Nadine Abdel Ghaffar, the head of the private art consultancy Art d'Egypte. "There is so much more to this country than what is portrayed. Once you are on the ground, you see past the dust and the chaos. People who live here don't want to leave; people who visit want to come back. This is not a regular country."

Egyptomania is a term coined in the 19th century to describe the mental state of the first wave of 19th-century European and American travelers agog at Egypt's ancient treasures. It is impossible not to be affected by seeing up close, in situ, the sublime creative impulses of the world's longest-lived ancient civilization. But it's more than that, I'm reminded as I make my rounds. There's the fundamental graciousness of many Egyptians, as if they are the inheritors of civilization in more ways than one, and even the sights and sounds of everyday life here can be powerfully affecting.

A memory I've carried since I was 12 is of a galabia-clad vendor making his way early one morning down our empty street on Zamalek alongside his donkey and cart, calling out something in singsong; the sun had just risen, the pyramids of Giza were visible in the far distance—as they then were from certain perches in central Cairo—and everything was suffused with a pale yellow light. My parents and I were leaving Cairo for America that day—my father, an architect, had been in Egypt redesigning the Nile riverfront in Aswan, under the auspices of the Ford Foundation—and I had just stepped out onto our terrace for a final look. I remember, too, the bittersweetness of that.

Over dinner one day this time around, I press Zahi Hawass, Egypt's most famous living archaeologist (he once served as the country's minister of antiquities and has appeared in dozens of documentaries about its treasures), to account for the hold Egypt can have on a person. "It's magic," he says. "It's like when you love someone. You never have an answer as to why."

King Tut's New Home

"We are building a new monument," says Tarek Tawfik, director general of the Grand Egyptian Museum, known as GEM. When finished, it will be the largest archaeological museum in the world, displaying Egyptian artifacts from eras ranging from the pre-dynastic (before 3100 BC) through the Greco-Roman (up to AD 395), and the most spectacularly sited: just 1.2 miles from the Giza pyramids and designed to harmonize in beautiful and complex ways with them. (The project's price tag is $1.1 billion, $750 million of it in loans from Japan. The opening date is in 2020—inshallah.)

GEM's star attraction will be that worldwide object of obsession, the boy-king Tutankhamen—all of the 5,400 artifacts Howard Carter discovered in his tomb (which has just reopened after a 10-year restoration) in 1922. And it won't just be a matter of numbers and masterpieces. "Our aim," Tawfik says, "is to reveal the man behind the golden mask." The curators' goal is to take visitors back to the Egyptian court of 3,500 years ago. "Because his is the only tomb from which we have the clothes, the jewelry, the footwear, the knickknacks of a king, we will be able to evoke his lifestyle, take you as close as possible to an ancient Egyptian pharaoh. You will feel, more or less, as if you're attending Tutankhamen's funerary procession."

A 35-foot-tall statue of Ramses II—the 13th-century BC pharaoh who secured Egypt's borders and greatly extended its influence—has already been installed in GEM's soaring entrance atrium. Otherwise the galleries are still empty, and I'm getting a taste of what's to come in the laboratories of the Conservation Center, where for five years already at least 44,000 artifacts have arrived, transferred from the old Egyptian Museum and sites all over the country, to be readied for modern museological display.

On a pillow, among the objects on the long white tables in the organics lab, lies a beautiful golden female figurine, her arms and face burned off. "She was in the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir in 2011," Dr. Iman Halaby, head of the lab, tells me, referring to the revolution eight years ago that precipitated at one point a rampage through the museum's galleries. "Part of the revolution was about destroying artifacts, destroying this other, ancient history of Egypt, so that religious history could be the only one. We will not enhance, just stabilize her. The damage will become part of her history."

GEM is more than a museum. With a research library, a children's museum, a conference center that can accommodate 1,000 people, an outdoor reception space for 20,000, and, nearby, the new Sphinx International Airport, built for charter planes and private jets (think weekends in Cairo), it is a cultural institution with global ambitions. "We are creating," Tawfik says, "the world's window on Egypt and a forum where different cultures can easily meet."

The Royal Mummies and More

"I was in Paris on a sabbatical year as a visiting professor when the Muslim Brotherhood were in power," Khaled el-Anany tells me. "I could see we were becoming a religious country. I am Muslim, but that is not Egyptian civilization. Egypt, for me, is Old Cairo. In one square kilometer you have the Coptic Hanging Church, you have the Ben Ezra synagogue, and you have the first mosque in Africa."

And now, right nearby, is the NMEC, the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, second in the triumvirate of Cairo's new generation of museum wonders. Its sand-colored pavilions and stepped plaza, below the Mokkatam Hills, overlook blue Ain al-Sira, the city's last natural lake, and beyond it the imposing medieval citadel of Salah al-Din—aka Saladin, Egypt's ethnically Kurdish 12th-century ruler, who led the Muslim campaign against the Crusaders.

The citadel remained the seat of Egypt's government until the 1860s. The galleries here, too, await the displays, but there's a temporary, one-gallery exhibition, "Egyptian Crafts Through the Ages," organized to give a taste of what's to come. The Royal Mummies will eventually be transported here from the Egyptian Museum and become NMEC's main draw, the way Tut will be for GEM. But just as riveting, if slightly more wonky, is the museum's larger purpose: to highlight the technologies of Egyptian civilization—how through the ages Egyptians wrote, wove, worked in wood, made jewelry, built homes, and more. (For at least an hour I go down some rabbit holes: the genius in the construction of Egyptian chariot wheels, the impossibly chic linen dresses worn even by ordinary tradespeople in ancient times.)

"We want to restore the Egyptian identity," says Mahrous Elsanadidy, NMEC's chief curator. "To tell our citizens and others what Egypt means." Burnishing Brand Egypt—and in the process pointing out its multicultural and inclusive history—seems key not just to the economy but to countering the blandishments of borderless Islamic fundamentalism.

A Relic Renewed

"It's why I love the old Egyptian Museum," says Ghaffar. "There's an energy there. It's like a third dimension." I'm talking to her about whether inanimate matter can have memory, whether stone, shaped by human hands thousands of years ago, can have spirit. The thought is peculiar, I'll admit, but it seems less so in Egypt. At the old Egyptian Museum, "you feel like you're living a thousand lives."

Which may have to do with the sheer number of objects jammed into its neoclassical columned galleries and overflowing storage facilities—some 170,000 of them. It's not the museum's fault; it has been the recipient, since it opened in 1902, of an unending stream of archaeological discoveries. As Hawass points out to me, "Only 30 percent of what's there has been discovered. Remember that modern Egypt was built atop ancient Egypt." I walk to the museum one evening—it's two minutes across Tahrir Square from the Ritz-Carlton—to see the progress of the restoration work, which is being done from the inside out while some of the treasures are being distributed in stages to GEM and eventually NMEC.

"Our idea," Neamatalla explains (the concept is the brainchild of his company, EQI, which specializes also in cultural preservation and is co-funding the project along with the European Union), "is to transform this 117-year-old antique into a 'museum of museums.' The only structure in the world reminiscent of what museums used to be. We are using the original drawings of the architect Marcel Dourgnon. By the time GEM opens, this will be another masterpiece of Egypt."

I see the results in some of the second floor galleries: cream and pale green walls, subtle Greek key motifs, crimson baseboards, burnished wood and glass display cases. An affecting but dusty attic of a place is being turned into a gleaming period boutique that will display, according to Sabah Abdel Razek, its general director, "the 5,000 iconic masterpieces of Egyptian history."

She steps back and paints the big picture. "When all the museums are finished, we will keep this one open every night, to give people who visited the pyramids and GEM in the morning time to come here afterward. There are plans for subways to connect all three, as well as the Coptic Museum, the Islamic Museum, the Textile Museum, and the Manial Palace. Perhaps helicopters, too, for VIPs."

Here is a vision of Cairo transformed into another sort of mecca—the world's premier art-historical destination.

Cairo Dinner Parties

"Go to a few cocktail parties and dinners and soon you will meet everyone," say Laila and Ekram Nakhla, Cairo's jewelers to the stars, when I drop by their shop, Nakhla, (historically inspired designs in 21K gold). "Cairo is small that way." I'm invited, and of course I go.

The Nile is exceptionally beautiful at night, the city's grittiness obscured by the darkness, the lights of bridges reflected in the calm black water. On terraces with views of the river, conversations among Cairo's cultural elite switch seamlessly among Arabic, English, and French. Past and present merge for me again: I remember this as a feature of my parents' parties, which were frequented by fluently multilingual Egyptians and expats.

A few people at the soirees I go to I have known since childhood. "Your father and mother used to come here a lot, you know," says Lea Boutros-Ghali, Cairo's clever, cultured grande dame, showing me around her art-filled apartment. She is the widow of the former secretary-general of the United Nations, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, whose legacy is highly appreciated here.

Over multiple courses and flowing wine, the topics range far and wide, from the mosaic of people to whom Egypt has been home ("Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Ottomans, Europeans of all stripes. Figuratively, we didn't resist anyone, and the culture was the richer for it") to press censorship today and the future of Jerusalem. From New Age kooks looking for evidence that Egyptians did not build the pyramids to Mohammad bin Salman and Jamal Khashoggi ("a battle of two evils, the crazy prince and the arriviste Muslim Brotherhood sympathizer"). From belly dancing to the country's superb mangoes and the possible influence of Egyptian culture on ancient Greek civilization (a heated debate). At the end of one evening there is much speculation about what exactly the oracle in the temple of Amun in Siwa Oasis said to Alexander the Great when he went to consult it in, oh, 332 BC.

And, of course, as is the case at every Egyptian table, there is talk about Sisi, the military man the Western press condemns for his strongman moves but who, in this statist country, has put his weight behind not just security and economic reforms but also cultural revival. For this crowd, academics, historians, entrepreneurs, and supporters of the arts, that may be enough for right now. Ghaffar is bracing on the topic: "From a cultural perspective, I think the army actually saved Egypt. What the Brothers were doing is not Egyptian. They wanted to change our culture. Imagine—the oldest civilization in the world." Lea Boutros-Ghali is categorical: "I'm a Sisi-awi. I voted for him twice. Because four years is not enough to do the job. After that, we can evolve."

The New Egypt

On one of my last evenings in Cairo, I start to see the outlines of an evolution at the opening party for "Nothing Vanishes, Everything Transforms," an exhibition of contemporary Egyptian art staged by Ghaffar. It is held at Manial Palace Museum and Gardens, the magnificent former residence on Rhoda Island, completed in 1937, of Prince Mohammed Ali Tewfik, a onetime heir to Egypt's throne. The prince, a European-educated painter and inveterate traveler and collector, built five distinctively styled buildings here, integrating European Art Nouveau and Rococo with traditional Islamic styles (Ottoman, Moorish, and Persian), and filled them with his extensive collections of art, furniture, clothing, objets d'art, tapestries—even butterflies.

It is against this backdrop of cross-cultural bricolage, which heralded Egypt's first, early-20th-century renaissance (a period of prosperity, calm, and modernization), that Ghaffar showcases 28 Egyptian conceptual artists. The works are installed throughout the property, in dramatically spotlighted gardens and pavilions, among which 700 invited guests amble on their way to speeches and dinner at long tables set up on a lawn. Here is a black polymer statue of a woman in a body-hugging dress reminiscent of what ancient Egyptians wore, provocatively called Opening Up, by Sarkis Tossoonian. Sixty dusty and neglected women's shoe molds sit in neat rows on green fabric at the entrance to the palace mosque (Waiting for Admission, by Huda Lufti). There is a multimedia installation in an ornate Khedive-era bed from which tumble tousled white sheets, riverlike, illuminated by changing light—Happy Ending or No Happy Ending, by Nadine H.

The guest list, which includes grandees from politics, journalism, business, and art, is strikingly cosmopolitan. To be sure, Cairo society, international art dealers, collectors, and academics from Egypt and elsewhere in the Middle East are here. But so are the Belgian, French, and Swiss ambassadors and a representative from the U.S. embassy, as well as the CEOs of BMW and Duravit, in addition to the head of UNESCO in Egypt and the director of the British Council. And, of course, the government is out in full force, represented by an impressive bevy of ministers: exterior, planning, communications and information technology, social solidarity, and antiquities, among others.

Looking out over the assembled, Samih Sawiris, an Egyptian billionaire businessman whose Sawiris Foundation helped fund the exhibition, tells me, "I don't see many occasions to spend money more wisely than promoting the modern Egypt, an Egypt that makes us proud and that you guys don't know. Ten years ago you could not even talk about having an event for young artists in a place like this." (Save-the-dates are out already for this year's exhibition, which kicks off on October 26 and will be staged on Old Cairo's fabled Moez Street.)

Khaled el-Anany, the minister of antiquities, offers brief opening remarks that pithily contextualize for me the cultural moment in Egypt: "Art is indispensable to our lives—whether we be Muslim, Jew, Christian, etcetera. Here, contemporary art and exquisite historic settings are engaged in an exquisite dialogue." Often referred to as the cradle of civilization, Egypt today—Mediterranean, Arab, and African—fuses antiquity and modernity in one grand vision, and celebrants of its culture insist that it be imagined, once again, as nothing less than the crossroads of the world.

Should You Go?

There is currently no State Department travel warning for Egypt, except for the Sinai and the Western Desert. (There is an advisory urging caution.) I have always found Egyptians to be welcoming, gracious, and happy to see Americans.

For the best experience, book your trip through a travel specialist who has deep on-the-ground contacts. Jim Berkeley of Destinations & Adventures International (JIM@DAITRAVEL.COM; 800-659-4599), with whom I have traveled to Egypt three times, has invariably excellent guides and will work with you to customize the best itinerary. You'll be picked up at airports, assisted with cars and drivers, and coddled as much as you desire.

In Cairo, where your trip will start, Berkeley will get you between the paws of the sphinx—worth every penny. My sentimental favorite among the city's hotels is the Marriott on Zamalek Island, largely for its great café in the back garden, frequented at all times of day by tourists and locals alike, as well as the Nile Ritz-Carlton, on Tahrir Square, just steps from the Egyptian Museum. Beyond Cairo—especially if it's your first visit—the musts are Luxor (stay at the Winter Palace or Al Moudira) and Aswan (stay at the Sofitel Old Cataract, one of the world's most superbly sited hotels—so taken with it was the Aga Khan that he chose to be buried directly across from it).

Book Now Cairo Marriott Hotel, Zamelek Island

Book Now The Nile Ritz-Carlton, Cairo

If you have the time, take a Nile cruise on the Luxor-Aswan segment of your trip. Especially in demand now are the dahabiyas, small, private vessels used by 19th-century travelers to Egypt. Only six to 10 cabins each, they can dock where larger ships cannot. Whichever type of vessel you choose, you will see passing slowly before your eyes a truly eternal Egypt.

This story appears in the April 2019 issue of Town & Country. Subscribe Now

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment