https://egyptmanchester.wordpress.com/2017/11/30/curators-diary-november-2017-my-first-trip-to-sudan/

Curator's Diary November 2017: My First Trip to Sudan

Last week I returned from six days in Sudan, my first ever trip to the country. Despite many visits to neighbouring Egypt, I have always wanted to visit Sudan but not quite managed. I have been especially aware of this since my appointment in 2011 as Curator of Egypt and Sudan at Manchester Museum, which holds some 2000 Sudanese antiquities. As a guest of staff at the British Embassy in Khartoum, I was very grateful for their hospitality and the logistical help afforded in seeing so much of this beautiful country over a short period. Tourism is not nearly as widespread in Sudan as it is in Egypt, which has definite advantages (and some drawbacks) for the interested visitor.

Sufi dancing at Omdurman

A personal highlight was witnessing Sufi dancing at the mosque of Hamed al Nil, at Omdurman just outside Khartoum, at dusk after Friday prayers. Although an earnest (if joyful) means of religious expression, I was stuck by the openness of participants to outsiders and was one of several Western onlookers being warmly welcomed. 'Whirling dervishes' (a term used for the principal participants) are often presented as something of a tourist sideshow, but what I experienced was unlike anything I'd seen in more tourist-oriented Egypt. The clouds of incense, bright green garments of some of those who took part (with tall crowns of almost 'Osirian' type), rhythmic drum beats and chanting evoked something very ancient. Most striking was the location of the performance next to a cemetery, a juxtaposition of the living and the dead which may seem strange to a Western audience but which is common to many ancient and living cultures. The lively dancing suggested the sorts of experienced but 'ephemeral' practices that simply do not survive in the archaeological record but which were nonetheless impressive and important.

Rocky outcrop at Gebel Barkal, interpreted in ancient times as a rearing cobra sacred to the god Amun

Over several days I was able to visit a number of archaeological sites. Sudan was home to a number of power centres between c. 750 BC and 300 AD – known variously as the Kushite, Napatan and Meroitic empires. Gebel Barkal, 400km north of Khartoum, is the site of a major temple to the god Amun begun by the Egyptian pharaoh Tuthmose III (c. 1481-1425 BC). It was later the spiritual home of a family of Kushite kings who ruled both Egypt and Kush as the 25th Dynasty of Pharaohs. Climbing the mountain at sunset provided an incredible view of surrounding landscape, and birds-eye view of the interconnections of monuments that ancient people will have known.

Pyramids at Meroe

It is now a well-known pub-quiz fact that Sudan has more pyramids than Egypt; these steep-sided examples are clustered mainly at the sites of Meroe, Nuri, El-Kurru and Gebel Barkal. Changing forms of scene content and stylistic expression are noticeable in the small adjoining decorated chapels of many pyramids, several of which have been restored after being blown up in the search for treasure by an Italian explorer in the 1830s. Unlike the Egyptian pyramids, these monuments sit essentially alone in the desert, far from encroaching conurbations, and as a result are highly photogenic. This may obscure their serious purpose as tombs. This funerary function is made clear in the painted burial chamber of Tanwetamani, the last king of the Kushite 25th Dynasty (c. 650 BC), at El-Kurru. Viewing of these vivid scenes by torchlight was another personal highlight.

Painted underworld images inside the pyramid of Tanwetamani

The largest cluster of pyramids is at Meroe, around 200km north of Khartoum. It was a special privilege to be given a tour of the current excavations at The Royal City of Meroe by Jane Humphris. Jane and her team are demonstrating that Meroe was a major centre of iron production, which fuelled a mighty military. It had been excavated at the beginning of the Twentieth Century by John Garstang, an archaeologist based at the University of Liverpool – my alma mater, but modern techniques are salvaging many details that Garstang overlooked.

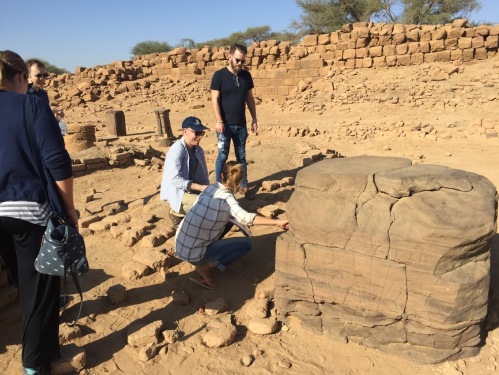

Appreciating a barque stand in temple at Royal City of Meroe

Having attended a fundraising ball held by the Khartoum Caledonian Society and met the British Ambassador Michael Aron, it was of interest to observe some of the mechanics of modern diplomacy in a country often characterised by Egyptologists as an 'imperial' possession of New Kingdom Egypt (c. 1450-1100 BC), echoing experiences of British colonialism in the Nineteenth Century AD. My visit also afforded the opportunity to speak with officials involved in international efforts to understand migration within Africa today and to tackle human trafficking and exploitation. Modern concerns reflect ancient realities, raising important questions about how ancient cultures such as those of Egypt and Sudan – but also of universal experiences such as migration – can be represented in museums.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment