https://brewminate.com/fortified-cities-in-ancient-egypt/

Fortified Cities in Ancient Egypt

The Lion Temple

Walls do seem to be a defining feature of many Egyptian settlements throughout the dynastic period.

By Dr. Steven Snape

Reader in Egyptian Archaeology

University of Liverpool

The origin of urbanism in Egypt includes the emergence of heavily defended walled settlements as major political and economic centres. The policy of providing enclosing walls for settlements continued in the Old Kingdom, although the extent to which these were necessary for defence against a genuine external threat has been doubted, apart from at border-towns like Elephantine. Walls do seem to be a defining feature of many Egyptian settlements throughout the dynastic period, particularly small-scale settlements, for reasons that may have had little to do with defence. However, there were clearly situations when a settlement required some form of specialized physical protection from hostile external forces. For most periods of Egyptian history providing that defence was the responsibility of the king.

Nubia in the Middle Kingdom

Although none has survived in the archaeological record, the presence of small watch-tower fortlets in the Early Dynastic Period is indicated by illustrations like this ivory label. British Museum, London.

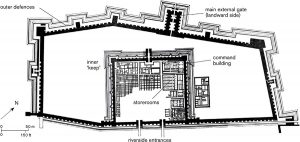

Perhaps the most sophisticated approach taken by the Egyptians to military architecture was the defence of the Second Cataract region, which was the border between Egypt and its hostile southern neighbour, Nubia, during the Middle Kingdom. Here a series of mutually supportive fortresses was created to form a network of defence. This was in turn backed up by a well-organized logistical system that was embedded within the design of each individual fortress. Some fortresses, such as Semna and Kumma, acted as a heavily defended frontline and their form was specifically adapted to their location overlooking the Nile, while others had specialist functions, such as Askut, which was effectively a fortified granary. Largest of them all was Buhen, which combined sophisticated external defences with an interior that indicates it was the administrative centre for Lower Nubia in the Middle Kingdom. If anything, Buhen most closely resembles other centrally planned Middle Kingdom settlements, such as Kahun, in its neat rectangular blocks of buildings.

Fortified Settlements in the New Kingdom

In the New Kingdom the evidence is less well preserved and less conveniently gathered than that for the Middle Kingdom Nubian forts. The re-occupied (e.g. Buhen) or newly established (e.g. Sesebi) Egyptian colonial towns of the New Kingdom were provided with thick enclosure walls, but with little of the ingenious defensive sophistication of the Middle Kingdom, suggesting that the threat they faced was, if it existed, low level.

A more serious approach was taken to the creation of fortresses and fortress-towns in frontier areas of genuine threat, including the 'Ways of Horus' chain of fortresses across northern Sinai and a comparable, although solely Ramesside, 'Libyan chain' stretching at least as far west as Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham. This site provides evidence for both military architecture in the face of a serious enemy and the operation of a real town with a mixed population and diverse local economy.

The Nubian fortress town of Buhen represents a high-point in the architectural complexity of Middle Kingdom military architecture. Steven Snape.

The Nubian fortress town of Buhen represents a high-point in the architectural complexity of Middle Kingdom military architecture. Roger Wood/Corbis.

However, the end of the New Kingdom saw the emergence of a series of enemies who posed a threat to the interior of Egypt itself. Part of the response to this was the provision of defences for vulnerable towns by surrounding them with a mudbrick wall of an intimidatingly massive height and thickness. This approach was the one adopted in the reign of Ramesses II for the defence of the vulnerable West Delta towns of Tell el-Abqa'in, Kom Firin and Kom el-Hisn. Another approach was the strengthening of existing defensive possibilities such as the temple enclosures/'urban citadels' of long-established cities. As a warning to the descendants of the Libyan enemies who had threatened the western Delta in the reign of Ramesses II, Ramesses III ordered the building of mudbrick walls 30 cubits (over 15 metres, 49 feet) in height around the temple enclosures of some of the most important towns in southern Egypt – the temples of Thoth at Hermopolis Magna, Wepwawet at Asyut, Onuris-Shu at This and Osiris at Abydos (this last was fortified so that it was like 'a mountain of iron'). As the guarantor of maat (order, and peace) the king could do no less.

The great 'migdol' gate of the mortuary temple complex of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu gives a sense of the intimidating but now-denuded gateways of New Kingdom fortresses-towns. Steven Snape.

At Thebes the enclosure of Ramesses III's mortuary temple at Medinet Habu provides the best model for what the fortresses on the Asiatic or Libyan borders may have looked like, with their enormous mudbrick walls and intimidating stone gateways. By the end of the New Kingdom this particular temple enclosure, whose external appearance was modelled on that of a fortress, had become the best-known example of a fortress-town in Egypt: a place where the residents of the Theban West Bank could live, protected from external enemies who were now very much an immediate threat.

From The Complete Cities of Ancient Egypt, by Steven Snape (Thames & Hudson, 09.16.2014), published by Erenow, public open access.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment