https://amarnaanniversary.wordpress.com/2017/11/05/monastic-footprints-at-amarna-trails-of-the-unexpected/

Monastic Footprints at Amarna: Trails of the Unexpected

Amarna has a rich post-New Kingdom history: Gillian Pyke gives a tour of its early Christian remains.

The abandonment of the ancient city of Akhetaten, shortly after the death of Akhenaten in about 1332 BC marked the demise of his vision of a society devoted to a sole deity. Some of the sacred spaces were dismantled and the suburban houses collapsed and filled with sand so that eventually there was little to see of the once-busy city. After a break of nearly two thousand years, monotheism, this time in the form of Christianity, made a return to the Amarna plain.

In the south is the monastery at Kom el-Nana, built over the comprehensively-razed Sun Temple of Nefertiti temple complex. The mud-brick monastic complex was my introduction to Egyptian archaeology, and first of many lessons in expecting the unexpected that characterises the experience of working in Egypt. Expectation led me to believe that I would be focussing on the material culture of the ancient city, but, unexpectedly, I found myself an apprentice ceramicist working on oh-so-late material. Somehow neither the pottery nor the post-pharaonic time period ever got shaken off, which is absolutely fine.

The Kom el-Nana monastic complex has its own idiosyncrasies, including the two or more towers/keeps and the two refectories, where most monasteries have only one of each. The rich material culture includes pottery that dates its occupation to between about the fifth and seventh centuries, with its heyday in the sixth century. Coins and ostraca offer a similar date range, the latter documenting economic transactions with the outside world. A completely unexpected discovery was the fallen plaster in the sanctuary of the monastic church, the fragments bearing tantalising colours and parts of words in the Coptic script. It was a jigsaw puzzle without the picture and with most of the pieces missing. How much more difficult could it be than joining brown sherds to other brown sherds? A bit, it turned out.

After several seasons of struggle, during which time most joins were notably made before 9 am, making an early start imperative, it was at least possible to determine the type of scene and pick out some salient details. Not unexpectedly, given the setting, the bipartite apse composition shows Christ Triumphant in its upper part and the twelve Apostles in the lower. The Apostles have their names conveniently placed between their feet, which are clad in white footwear with black heels and toe-caps, nick-named 'Coptic socks', presumably entirely inaccurately. Most of them hold a rolled-up scroll but Peter clutches the key to the Gates of Heaven and (probably) John holds a large book that represents his Gospel(s). Both the scene and the painting techniques have close parallels at the nearby Monastery of Apollo at Bawit, occupied at much the same time.

The many hours spent trying to join fragments of green cloak (John's? Bartholomew's?) were regularly punctuated by helpful comments from other team-members that 'As you like that late stuff so much, why don't you do something at the North Tombs?' OK, why not? The project followed in the illustrious footsteps of Norman de Garis Davies, who had already (at the turn of the twentieth century) attributed the cobble-built structures around the North Tombs to early Christians rather than the dynastic tomb-builders.

After quite a number of years of fieldwork in Egypt, it should have come as no surprise that first the church and then the settlement was much more complex (and in the latter case) extensive than expected. The challenges of the church started with the long, long walk up the steep slope to the Tomb of Panehsy, located at the far eastern end of the North Tombs. The walk got longer every day, not aided by the sight of Foxy and Loxy, two of the local foxes, sprinting up virtually vertical slopes just to show us how it was done.

The painstaking work of recording the details of the church conversion were certainly worth the trek and eventually its secrets were revealed. The detection of tiny details of changes in floor surface lines of post-holes and slots in columns allowed us to reconstruct how the dynastic tomb was converted into a monastic church. Sherlock Holmes would be proud, but would presumably tell us it was elementary. His wise advice that 'when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth' also resonated during the struggle to understand the apse composition, a unique and deliberately damaged six-winged bird. Birds were an important means by which the divide between Heaven and Earth could be traversed, especially in the world of early Christian monasticism in Egypt. Desert monastics in particular, like Onophrius and Paul of Thebes were supplied with bread by crows sent directly from Heaven. The phoenix could symbolise resurrection. The bird here, however, is more likely to be an eagle, another symbol of the triumph over death and here representing Christ, the beating wings perhaps capturing the exact moment of transformation. The image is particularly appropriate to the elevated position of the church and settlement, where similar birds are often seen soaring.

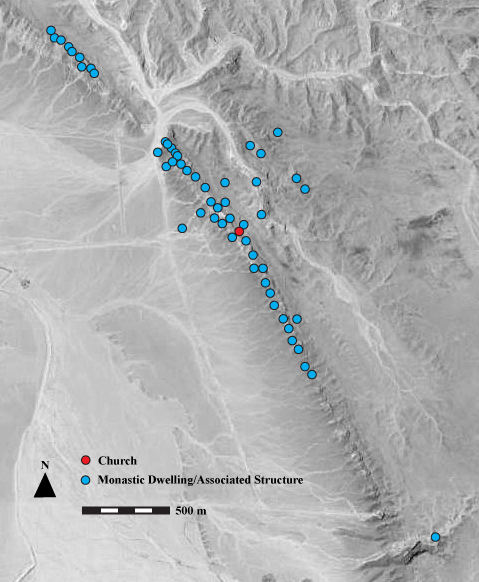

Unexpectedly, the monastic settlement extended along the cliffs far to the east of the North tombs and back into the high desert, using both tombs and caves as the focus of each residence. Its investigation saw us literally following in the footsteps of its ancient monastic inhabitants, often using their footpaths and staircases to traverse the landscape. Despite these routes of communication, the cliffs, gullies and boulders of the desert provided physical barriers that created the necessary solitude for each monastic dwelling.

It was also very quiet, another quality that encouraged withdrawal to the desert by monastics requiring an absence of distractions in order to achieve their spiritual practice. Somehow, distractions were still possible to find, most often in the form of the local wildlife, such as the bats, snakes and foxes that are the modern tenants of the settlement and its environs.

Watching a family of young foxes at play in one of the monastic structures (never mind, we will record it next time!), it was hard to imagine how the monastic inhabitants could envisage the landscape as a place where demons lurked. On other occasions they could be all too close, like the 'Mountain of Doom' a skull-like outcrop overlooking a group of residences set back in the desert – guaranteed to give you the shivers.

Then there was the weird quality to the light over several days in 2010, which turned out to be due to the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull (hurray for our Danish team members who could actually pronounce the name) rather than demons. It would also be easy to see demons in the sandstorm that, from our high viewpoint, we could witness rolling in from miles away to make our last day of one of the seasons unexpectedly complicated. Fortunately, Amarna had trained us to expect the unexpected and we managed to finish the work and descend, thanks to the monastic paths, safely from the cliffs.

Next on the monastic trail is the Great Wadi cave complex, a small monastic outpost similar in style to the North Tombs settlement set high-up at the head of the wadi. Although accessed by an adventurous (and significantly taller) Amarna team-member in the early 90s, subsequent attempts to reach the caves have been unsuccessful. To misquote Brody in the 1975 film 'Jaws', we're going to need a bigger ladder.

Gillian Pyke is a ceramicist and specialist in the archaeology of early Christianity in Egypt. From 2007 she directed the Panehsy Church Project recording the Christian re-use of the North Tombs. She has contributed to the study and publication of pottery from the Kom el-Nana monastery and her book on its wall paintings is in preparation. Her book on the North Tombs settlement is in the planning stages.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment