https://brewminate.com/harpers-songs-of-ancient-egypt/

Harper's Songs of Ancient Egypt

Harper's songs were lyrics composed in ancient Egypt to be sung at funeral feasts and inscribed on monuments.

By Dr. Joshua J. Mark

Professor of Philosophy

Marist College

Introduction

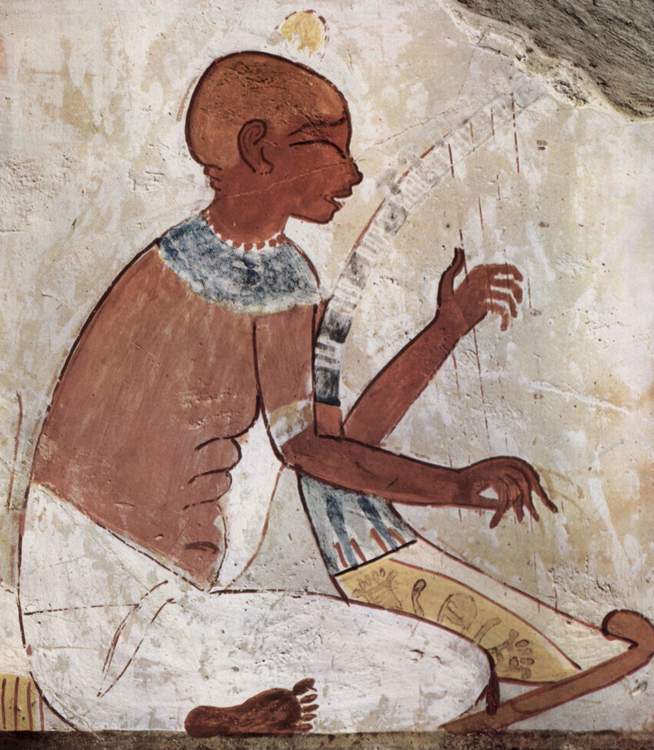

Harper's songs were lyrics composed in ancient Egypt to be sung at funeral feasts and inscribed on monuments. They derive their name from the image which accompanies the text on tomb or chapel walls, stelae, and papyri in which a blind harper is shown singing his composition to the deceased and sometimes the family of the departed. They appear in a rudimentary form in the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE), where they are brief salutations to the deceased, who is embarking on the next phase of existence, and praise for the certainty of the afterlife but were more fully developed during the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) when they underwent a significant change.

The best-known harper's song from the Middle Kingdom is The Lay of the Harper which originally appeared in the tomb-chapel of a king named Intef (though which Intef this was is unknown since a number of kings from the period took that same throne name) and expresses a novel skepticism of the traditional view of the afterlife in ancient Egypt. The Lay of the Harper explores a carpe diem theme, encouraging people to enjoy life while they can because what comes afterwards is unknown, and focuses on present pleasures.

This theme is refuted in the New Kingdom (c. 1570 – c. 1069 BCE) by the best-known harper's song of that period, A Harper's Song from the Tomb of Neferhotep, which dismisses the skepticism as nonsense. This piece questions what good can come from doubting eternal life in The Field of Reeds and directs an audience to rejoice and have hope in the traditional view of the afterlife. The New Kingdom is the last period in which harper's songs were composed.

Although the harper's songs have routinely been interpreted as reflecting the eras they were composed in, this claim has, and should, been challenged. A far more certain interpretation is that they reflect the age-old divide between religious faith and skepticism which expresses itself in the modern day in very much the same way as in ancient Egypt or in any culture from any period.

Egyptian Funerary Rites

Contrary to popular opinion, the ancient Egyptians were not obsessed with death. Rather, they valued life so greatly that they wished it to continue forever. The concept of the survival of bodily death was already part of cultural belief in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 – c. 3150 BCE) as evidenced by grave goods included in burials and was fully developed by the time of the Old Kingdom when the famous pyramids at Giza were constructed.

The traditional view of death held that it was not the end of life but only a transition to the next phase of the soul's eternal journey. The soul of the deceased would awake in its tomb, be led to the Hall of Truth by the god Anubis, and be judged by Osiris in the presence of Ma'at, Thoth, and The Forty-Two Judges. If the soul was found worthy, it was justified and continued on to The Field of Reeds where it would find all that it thought had been lost at death, would reunite with loved ones who had passed earlier, and would then live eternally in paradise in the presence of the gods.

In order for any of this to happen, however, funerary rituals had to be carefully adhered to. The body needed to be preserved in order for the soul to continue to receive sustenance and the tomb had to be prepared so the soul could bring with it all the provisions it would need on its journey to paradise. The body would be prepared by the embalmers and would then be transported to the place of burial. This procession would include professional mourners (always women) known as The Kites of Nephthys, imagined as birds of the goddess who comforted the dead, who would wail loudly to encourage others to express their grief.

It was thought that the dead could also hear the mourners and the soul would be enlivened in the knowledge they had lived a good life and would be missed. The mourners would sometimes recite the poem The Lamentations of Isis and Nephthys, a work probably composed during the Middle Kingdom, in which two female singers dramatically reenacted the grief of the goddesses over the death of Osiris.

The Lamentations was sung to the accompaniment of musical instruments but it, like the hymns and prayers of the priests, was ritualized. Whether it was performed at a funeral or a festival, The Lamentations was always performed the same way because it was associating an audience – whether the living or the deceased – with Osiris' death, resurrection, and eternal life. Works like The Lamentations encouraged the traditional view of death as a new beginning and a harper's song was supposed to do the same.

Once the deceased was sealed in the tomb, the funeral guests would celebrate the departed with a feast and it is thought that this was when the harper would sing his song. Unlike The Lamentations, each harper's song was different, tailored specifically to the individual, but all – initially – emphasized the promise that death was not the end and life was only one part of an eternal journey.

Harper's Songs in the Middle Kingdom

This Old Kingdom paradigm was continued in the Middle Kingdom as evidenced in harper's songs such as the one from the Stela of Nebankh (a steward of the king) of the 13th Dynasty. On the stela, the deceased is pictured sitting at a table while the harper squats, lower than he, to sing the song:

The singer Tjeniaa says:

How firm you are in your seat of eternity,

Your monument of everlastingness!

It is filled with offerings of food,

It contains every good thing.

Your ka is with you,

It does not leave you,

O Royal Seal-bearer, Great Steward, Nebankh!

Yours is the sweet breath of the north wind!

So says his singer who keeps his name alive,

The honorable singer Tjeniaa, whom he loved,

Who sings to his ka every day. (Lichtheim, Middle Kingdom, 194).

The ka was one aspect of the soul and needed to be sustained in order for the transformed soul to continue in the afterlife. Families would hire ka-priests to tend the tomb, if they had not the time, who would recite prayers for the deceased, bring food and water, and keep their name alive. As the Stela of Nebankh shows, this same was accomplished through a harper's song even though a ka-priest would probably also have been employed if one could afford it.

The song of Tjeniaa emphasizes the beauty of the tomb as a "seat of eternity" and "monument of everlastingness" and promises Nebankh will live forever not only through the goods in the tomb but through the health of his ka, his soul, which Tjeniaa will keep alive through his song. The tomb was one's eternal home to which the soul would return to be refreshed and visit earth, drawn by statues and images of one's likeness and, of course, the body. One did not need to fear death or cling to life because one would live on through other people's remembrance and the justification by the gods who had recognized one's virtue as well as one's tomb which would be attended by the living and would last forever.

This vision is presented quite differently in the better-known Lay of the Harper from the tomb of King Intef:

Fortunate is this prince,

For happy was his fate, and happy his ending.

One generation passes away and the next remains,

Ever since the time of those of old.

The gods who existed before me rest now in their tombs,

And the blessed nobles also are buried in their tombs.

But as for these builders of tombs,

Their places [tombs] are no more.

What has become of them?

I have heard the words of Imhotep and Hardedef [sages of the Old Kingdom]

Whose maxims are repeated intact as proverbs.

But what of their places?

Their walls are in ruins,

And their places are no more,

As if they had never existed.

There is no one who returns from beyond

That he may tell of their state,

That he may tell of their lot,

That he may set our hearts at ease

Until we make our journey

To the place where they have gone.

So rejoice your heart!

Absence of care is good for you;

Follow your heart as long as you live.

Put myrrh on your head,

Dress yourself in fine linen,

Anoint yourself with exquisite oils

Which are only for the gods.

Let your pleasures increase,

And let not your heart grow weary.

Follow your heart and your happiness,

Conduct your affairs on earth as your heart dictates,

For that day of mourning will surely come for you.

The Weary-Hearted does not hear their lamentations,

And their weeping does not rescue a man's heart from the grave.

Enjoy pleasant times,

And do not weary thereof.

Behold, it is not given to any man to take his belongings with him,

Behold, there is no one departed who will return again. (Simpson, 332-333)

This piece dismisses the idea that the dead can hear anything (the Weary-Hearted do not hear the mourner's lamentations) or that one's tomb guarantees continued existence. Further, since no one has come back from the dead to give proof of an afterlife, there is no reason to set one's hopes too high on the goodness and mercy of the gods and one would do better, the poet says, to follow one's heart and enjoy life as much as possible.

The Lay of the Harper is not the only piece of Middle Kingdom literature to express this view. Another famous work is A Dispute Between a Man and his Soul which makes the same point. The recognition that one's tomb will crumble, could easily be forgotten and lost, and so is no guarantee of eternal life, is expressed in yet another work, A Ghost Story (sometimes translated as Khonsemhab and the Ghost). In this piece, a ghost appears to Khonsemhab, High Priest of Amun, complaining that his tomb has fallen into ruin and no one remembers him anymore. Consequently, he is starving in the land of the dead and wanders without a home. Khonsemhab promises he will restore the ghost's tomb, and keeps his word, but an audience is still left to wonder about the many other tombs which fell and were not restored and the fate of those they were built for.

Harper's Songs in the New Kingdom

Scholars continue to debate whether these Middle Kingdom texts honestly reflect the Egyptian culture of the time or were literary conceits and personal opinions. Since harper's songs or short fiction like A Ghost Story were not ritual texts, scribes had freedom of expression to explore whatever theme they were interested in. An individual scribe might doubt the existence of the afterlife or the gods and express that in writing, but this does not mean Egyptians in general felt the same way.

Still, some scholars have pointed out that New Kingdom literature, for the most part, refutes the cynicism of Middle Kingdom literature, and this argues for a cultural backlash against an earlier collective skepticism. The best-known refutation of the view expressed in The Lay of the Harper is A Harper's Song from the Tomb of Neferhotep of the New Kingdom which encourages the traditional view of the eternal paradise awaiting after death:

All ye excellent nobles and gods of the graveyard,

Hearken to the praise-giving for the divine father,

The worship of the honored noble's excellent ba,

Now that he is a god everlasting, exalted in the West;

May they [the praise] become a remembrance for posterity,

For everyone who comes to pass by.

I have hard those songs that are in the tombs of old,

What they tell in extolling life on earth,

In belittling the land of the dead.

Why is this done to the land of eternity,

The right and just that has no terrors?

Strife is abhorrent to it,

No one girds himself against his fellow;

This land that has no opponent,

All our kinsmen rest in it

Since the time of the first beginning.

Those to be born to millions of millions,

All of them will come to it;

No one may linger in the land of Egypt,

There is none who does not arrive in it [death].

As to the time of deeds on earth,

It is the occurrence of a dream;

One says: "Welcome safe and sound",

To him who reaches the West [afterlife]. (Lichtheim, New Kingdom, 115-116)

This scribe emphasizes the brevity of life ("it is the occurrence of a dream") which cannot possibly matter when compared with the eternal paradise which waits beyond death. Everyone will be there ("all our kinsmen rest in it") and, as the last line makes clear, every justified soul is welcomed home, safe and sound.

The New Kingdom was the period of Egypt's empire when the country was expanding, the economy was booming, and the citizens had every reason for optimism, and so it may be supposed that this type of harper's song is a response to that. Some scholars have pointed this out, claiming that the prosperity of the country was reflected in its art. The Middle Kingdom, however, was equally prosperous – considered by many scholars and historians to be Egypt's Golden Age – and so, if one accepts the prosperity=optimism theory, Middle Kingdom poetry should be as bright and hopeful as that of the New Kingdom.

It has also been suggested that Middle Kingdom poets were reacting to the chaos of the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE) which preceded it, but this makes no sense for two reasons. The First Intermediate Period was not that chaotic and was, in fact, a time of artistic diversity and cultural growth, and, if the Middle Kingdom's cynical poetry was a response to a difficult past, then New Kingdom scribes had much better reason to pen much darker verse since The Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782 – c. 1570 BCE) has a better claim to being chaotic than the First in every way.

Further, not all New Kingdom literature adheres to the traditional, hopeful, view of the afterlife. The piece known as The Immortality of Writers points out that tombs crumble and monuments fall but a writer's work guarantees immortality as the author lives on through an audience. The Immortality of Writers, in fact, makes the same point as The Lay of the Harperor A Ghost Story in that one's tomb can be forgotten but what one does in life will always be remembered – and most certainly if one is a scribe.

Conclusion

Far from only serving as a barometer for the culture's values, harper's songs are individual expressions of faith – or the lack of it. As noted, this genre was not ritualized and one was free to compose whatever one wanted, within reason. The central value of ancient Egypt was ma'at – harmony – which kept the individual and the community in balance. Too much of any given thing, whether a line of thought or type of behavior, could throw that balance off and cause problems.

A belief in the afterlife and the gods was encouraged because of the stability it offered but nowhere in Egypt's history were the pleasures of life or their pursuit, in moderation or at the proper times, condemned. The Lay of the Harper leans too far in one direction while A Harper's Song from the Tomb of Neferhotep too far toward the other: the one disparages eternity; the other life on earth. Neither of these views are a reflection of Egypt's values in any period; they are the views of the artists who composed them and continue to resonate today because they reflect the eternal question of how best to live one's life.

Bibliography

- Bunson, M. The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. (Gramercy Books, 2009).

- David, R. Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt Revised. (Oxford University Press, 2007).

- David, R. Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt. (Penguin Books, 2003).

- Lichtheim, M. Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms. (University of California Press, 2006).

- Lichtheim, M. Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume II: The New Kingdom. (University of California Press, 2006).

- Lichtheim, M. Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume III: The Late Period. (University of California Press, 2006).

- Pinch, G. Egyptian Mythology. (Oxford University Press, 2004).

- Shaw, I. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. (Oxford University Press, 2006).

- Simpson, W. K. et. al. The Literature of Ancient Egypt. (Yale University Press, 2003).

- Wilkinson, R. H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. (Thames & Hudson, 2017).

Originally published by the Ancient History Encyclopedia, 08.27.2019, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment