https://slate.com/culture/2018/10/mummy-curse-titanic-sinking-washington-post-article.html

One Month After the Titanic Sank, the Washington Post Suggested a Mummy's Curse Was to Blame

One of the great pleasures of reading old newspapers is their credulous approach to the supernatural. The modern-day San Francisco Chronicle would presumably not run an article headlined "A HEADLESS GOBLIN," reporting that a Missouri man found nude in the street claimed his clothing had been stolen by—you guessed it—a headless goblin, but the Chronicle of 1887 was more than happy to. The New York Times' definition of news that was fit to print was once expansive enough to include stories like "A Homicide Pursued by the Ghost of His Victim" (June 20, 1869), "A Talking Ghost in Virginia" (Feb. 2, 1871) and "A Talking Ghost in Nevada" (Nov. 24, 1872). And the Washington Post had an absolute mania for these sorts of stories into the early twentieth century. Between 1904 and 1912, the paper ran four lengthy feature articles about the supposed exploits of a single cursed mummy, the Unlucky Mummy, under these probably not-entirely accurate headlines:

• "Face on Mummy Cace [sic] Comes To Life Again," June 19, 1904.

• "Strange Mystery of a Mummy: Is This Priestess Still Alive At the Age of 3500 Years and Capable of Exercising Her Weird Powers?" April 26, 1908.

• "Coffin Carries Curse: Mummy Case of Priestess Has Sinister Record," Sep. 17, 1910.

• "Ghost of the Titanic: Vengeance of Hoodoo Mummy Followed Man Who Wrote Its History," May 12, 1912.

That last headline means exactly what you think it does: less than a month after the Titanic sank, the Washington Post ran a story blaming the whole thing on a mummy's curse. It's unclear why the Post covered the cursed mummy beat so doggedly, although their decision to end the 1912 version of the story with a lengthy excerpt from William Butler's autobiography suggests that filling space was a concern, as does their decision to refer to Butler's autobiography as "the autobiography of the late Lieutenant General the Right Honorable Sir William F. Butler, Grand Commander of the Bath, which was published last year by Constable & Co., Ltd., of London." Still, it matters what you use to fill space, and if you're going to publish fake news, better that it be about cursed mummies than, say, "economic insecurity." So just in time for Halloween, here's the complete text of the all-time hottest take on the sinking of the Titanic, as published in the newspaper that eventually cleaned up its act enough to sink Nixon. –Matthew Dessem

Ghost of the Titanic

VENGEANCE OF HOODOO MUMMY FOLLOWED MAN WHO WROTE ITS HISTORY

Was the avenging spirit of an Egyptian priestess who died in the holy city of Thebes 1600 years before the birth of Christ present upon the Titanic, pursuing with immortal malevolence those who had desecrated her tomb and her memory? Did the curse pronounced 35,000 years ago by the storied Nile upon all who should insult her bones have power to rush down the centuries into the age of wireless telegraphy and the waters of the New World?

In the twentieth century, with its general rejection of the supernatural, these questions will at once be pronounced absurd. But even now persons will be found to take the problem seriously, because of the mysterious series of shocking tragedies which have befallen all who had to do, either in deed or in word, with the mummy case of a priestess of the College of Amen-Ra which now stands in the First Egyptian Room of the British Museum.

Among those who would not have been skeptical was the famous English editor, William T. Stead, who perished when the Titanic foundered, and who would, in all probability, consider himself as the latest of the long line of victims of the priestess's ancient malice.

Although trained in the modern rationalistic thought, Stead had a strong bias toward the supernatural, as was shown in his well-known interest in occultism and Spiritualism. At the saloon table of the Titanic he related to a fellow passenger, Frederick K. Seward, an uncanny tale of the adventures of the mummy in the British Museum, which had punished, he said, with great calamities all who had written his story. He told of one person after another who had come to disaster after writing its sinister history.

"I know the story, but I shall never write it," added the veteran publicist, thus betraying how powerfully the somber doom of many less credulous persons had affected him.

Stead did not say whether ill luck would attend the mere telling of the story, but it is difficult to see what distinction the malignant priestess would make between the written and the spoken word. The difference in affront would seem to be at most one of degree, not of kind. At any rate, a few hours after Stead related the grewsome narrative with obvious respect, his body lay lifeless beneath 2,000 fathoms of water.

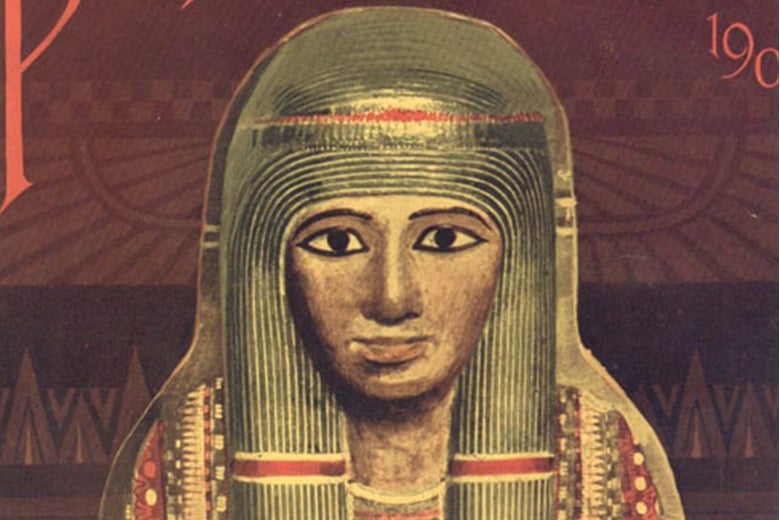

The perilous tale, as related by Stead, was probably in gist as follows, the account being taken from the English edition of Pearson's Magazine for August, 1900.

About 1,000 years before Christ, a priestess of the College of Amen-Ra lived and died in the mighty city of Thebes. Possibly she was a royal personage; she appears at least to have been of high rank, but of her name and life-history nothing is known. No doubt her body was embalmed with all the care that the Egyptians, particularly the priests, bestowed upon this work, an essential part of their religion. The mummy was inclosed in its wooden shell and placed in the appointed burial place of the priests and priestesses of the college.

Probably the burial place was carefully hidden, for the object of embalming was that the body should remain preserved for the use of its owner on her return from the under-world; and the body of the priestess lay in peace through the centuries, until at last it was disturbed by a roving band of Arabs. This was about 60 years ago, and in some way the mummy was separated from its case, and disappeared.

About the middle of the sixties a party of five friends went in a dahabia for a trip up the Nile. They went to Luxor, on their way to the Second Cataract, and there explored Thebes with its temple to Amen-Ra, unequaled on earth for its ruined magnificence.

A well-known English lady of title entertained the party, and the Consul, Mustaph Aga, gave a fete in their honor. One night, the Consul sent to his friends an Arab, who reported that he had just found a mummy case of unusual worth.

Next morning he brought the case for inspection. It bore the painting of a woman of strange beauty, but the dark eyes stared into vacancy with a cold malignity of expression. The case was brought by one of the party, Mr. D., who, however, agreed to draw lots for possession of the treasure; and the case passed to a friend, who may be called Mr. W.

Almost immediately it was recalled afterward with awe the vengeance of the ancient priestess began to display itself. It was as if she were hovering, a gloomy and implacable Nemesis, above them, armed with power to strike them even in their financial affairs in distant London. On the return trip one of the members of the party was shot accidentally in the arm by his servant, through a gun exploding without visible cause. The arm had to be amputated. Another died in poverty within a year. A third was shot. The owner of the mummy case found on reaching Cairo that he had lost a large part of his fortune, and died soon afterward.

If the inferences of the tale are to be believed the spirit of the priestess, with unappeasable wrath, did not halt at the confines of Egypt, but pursued the despoilers of her wooden shroud even to Great Britain. When the case arrived in England it was given by its owner, Mr. W., to a married sister living in London. At once large financial losses were suffered.

One day the famous theosophist, Mme. Blavatsky, entered the room in which the case had been placed. She soon declared there was a malignant influence in the room. On finding the cover, she begged her hostess to send it away, declaring it to be a thing of the utmost danger. The owner, however, laughed at this idea as a foolish superstition.

Presently she sent the case to a well-known photographer in Baker street. Within a week he called upon her in great excitement to say that although he had photographed the case with the greatest care, and could guarantee that no one had touched either his negative or the photograph, the portrait showed the face of a living Egyptian woman staring straight before her with an expression of singular malevolence. Soon afterwards the photographer died suddenly and mysteriously.

About this time Mr. D. happened to meet the owner of the coffin lid, and, hearing her story, begged her to part with it; and she sent it to the British Museum. The carrier who took it died within a week and the man who assisted him met a serious accident.

This is the history as it was verified by the late B. Fletcher Robinson, who for three months was at pains to gather the tangled threads of evidence, and who declared that every one of the fatalities was authentic. He himself seems to have thought that when the mummy's case arrived at the Museum, the anger of the spectral priestess would at last be appeased, for he wrote:

Perhaps it is that the priestess only used her powers against those who brought her into the light of day, and kept her as an ornament of a private room; but that now, standing among Queens and Princesses of equal rank, she no longer makes use of the malign powers which she possesses.

How poor a prophet Robinson proved was shown a few weeks after he penned this hope, when he himself died at an early age, after a brief illness. And now, as the latest link in the chain of disasters intimately connected with the painted mummy case, comes the tragic death of William T. Stead, at the height of his powers and fame, soon after he had ventured to relate the sinister story of the Theban priestess.

The Egyptian's religious faith in the resurrection of both the soul and the body, which students hold is embodied in the Apostles' Creed, made the rifling of a tomb the most infernal of impieties. It was held that if the soul returned from its journey to the under-world and was unable to find its body, it would be compelled to wander for eternity, unhoused, forlorn, and accursed. Hence the art to which the Nile dwellers brought the art of embalming, by which bodies have been preserved even unto to-day; hence, the enormous labors of the pyramids, the tombs of Egyptian Kings, whose bulk has defied time and those cunningly intricate passages, concealing the royal sarcophagi, frustrated until recently the curiosity of man; hence the frightful imprecations written upon the mummy case against irreverent hands which would molest them.

The mummy case in the British museum is not the first Egyptian relic which has been credited with malign powers. Two such cases are recorded in the autobiography of the late Lieutenant General the Right Honorable Sir William F. Butler, Grand Commander of the Bath, which was published last year by Constable & Co., Ltd., of London.

The author told of meeting a number of newspaper correspondents during the campaign to relieve Gordon at Khartoum. One of these, he related, was "one of the most dauntless mortals I ever met in my life. The story of his end is so strange that I must tell it here."

"I first met him in California in 1873," Sir William continued, "on my way from British Columbia to the West Coast of Africa. We next met at the Cataract of Dal, where I found him attempting to work up the Nile in a tiny steam launch which held himself, a stoker, and one other person. He was wrecked shortly after, but got up with the naval brigade, made the desert march and was present with Lord Charles Beresford in his action at Wad Habeshi, above Metemmeh.

"On his way up the Nile he had indulged in the then, and now, fashionable tourist pursuit of tomb-rifling and mummy-lifting, and he had become possessed of a really first-class mummy, which, still wrapped in its cere-cloths, had been duly packed and sent to England.

"When the Nile expedition closed he went to Somaliland, and, somewhere in the foothills of Abyssinia, was finally killed by his elephant and was buried on a small island in a river flowing from Abyssinia southward. The mummy got at Luxor eventually reached London. The correspondent's friends, anxious to get their brother's remains to England, sent out a man with orders to proceed to the spot where he had been buried and bring the remains home.

"This man reached the river, together with the Somali hunters who had accompanied the deceased on the hunting expedition the previous year, but no trace could be found of the little island on which the grave was made. A great flood had descended from the Abyssinian mountains, and the torrent had swept the island before it, leaving no trace of grave or island.

"Now comes the moral. The mummy was in due time unwound in London, and the experts in Egyptology set out to decipher the writings on the wrappings. Truly were they spirit rappings! There, in characters about which there was no caviling on the part of the experts, was written a varied series of curses upon the man who would attempt to disturb the long repose of the mummified dead.

" ' May he,' ran the invocations, 'be abandoned by the gods. May wild beasts destroy his life on earth and after his death may the floods of the avenging rivers root up his bones and scatter his dust to the winds of heaven.' "

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment