https://hyperallergic.com/434377/colonialist-myth-frenchman-saved-pyramids/

The Colonialist Myth of the Frenchman Who "Saved" the Pyramids

The troubling story fits a tired orientalist theme: Europeans and Americans know more, and care more, about the culture and heritage of West Asia and North Africa than their own inhabitants.

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. — We all love tales of the ancient Egyptian past — mummies, tombs, and pharaohs. Perhaps now more than ever, we love tales of threats to the ancient past and how those threats are averted. Scholars love those tales, too. One such story that scholars love to keep telling is how Muhammad Ali — Muhammad Ali Pasha, ruler of Egypt in the early 19th century, that is — nearly destroyed the Pyramids.

It's Egypt in the 1830s: Muhammad Ali has spent years trying to industrialize and modernize his country. He has recently approved a plan, put forward by his European engineers, to build a barrage (the French name), a dam across the Nile Delta to aid irrigation for farming. Concerned about obtaining construction material, Muhammad Ali realizes there is an abundant source of already quarried and worked stone — the Pyramids of Giza. Muhammad Ali's proposal, in short, is to demolish the Pyramids.

One of Muhammad Ali's leading engineers, the French-born Louis Marie Adolphe Linant de Bellefonds, is shocked by the proposal and devises a plan to save the Pyramids. Linant proposes a commission, with himself at the head, to study what would be involved in dismantling them and transporting them to the barrage and how much this would cost. Linant conscientiously prepares a report on his findings. At the same time, he makes a comparison with the cost for using the quarries of Cairo instead, which he finds to be cheaper. Once he presents the comparison to Muhammad Ali, the ruler drops the idea of dismantling any of the Pyramids.

The Frenchman who saved the Pyramids makes a great tale. But what's the truth behind it?

The early 19th century was a time of massive damage to ancient monuments and antiquities in Egypt. The destruction is attested to by both European and Egyptian sources. Europeans largely blamed Egyptians – the fellahin (peasants), but above all, the government, which was singled out for dismantling monuments to use their stones as building material. (In fact, this reuse had always been practiced in a region where new stone was not necessarily cheaply available, but it accelerated in a time of new building.) Jean-François Champollion, the French scholar who had deciphered ancient Egyptian, warned Muhammad Ali that at least 13 temples had been completely destroyed over the previous 30 years. It was often local governors who conducted the dismantling, but the pasha was claimed by the British and French to be indifferent, or even directly implicated in this destruction. Certainly, we know of examples where the highest levels of Muhammad Ali's government were directly responsible.

In the case of the Pyramids, we have more evidence: One of Muhammad Ali's officials, the engineer Joseph Hekekyan, had some years earlier written in his journal about the possibility of using some of the pyramids' stones for building projects. In February of 1836, the French political theorist and social reformer Prosper Enfantin reported that the Pasha had sent Linant and his committee to study the Pyramids. And, in the following months, it was reported in newspapers and journals throughout Europe and America that the Egyptian government was planning to dismantle the pyramids for the barrage, and that the Egyptians later abandoned this plan because it would be cheaper to quarry new stone.

The Western world reacted in horror. Muhammad Ali was derided as a megalomaniac. Not everyone felt this way, though. Enfantin thought it "poetic" to reuse the remains of the past in a greater and more useful way — "the most beautiful transformation" of remains that the centuries could not destroy but humanity could.

But none of these news reports mention Linant's role in saving the pyramids. In fact, it appears that the only source for the story of Linant being the savior of the pyramids is Linant himself. Since Linant presents it as his private plan, this would make sense, but it is very convenient, and it means researchers lack any proof. What we do know is that Linant loved to tell this story, from the 1830s all the way up to the 1870s. He told it about the Great Pyramid of Khufu. He told it about all three pyramids of Giza. He told it about Muhammad Ali; he apparently told it about Muhammad Ali's son Sa'id Pasha; and he apparently told it about Muhammad Ali's grandson Abbas Pasha. And he was sure to tell that he did his work "conscientiously."

What makes Linant's claim both dubious and troubling is that it fits a tired orientalist theme: Europeans and Americans know more, and care more, about the culture and heritage of West Asia and North Africa than their own inhabitants.

The reality is that local residents, though having a variety of views of the ancient past, often cared more than they were credited. While some Muslims considered the remains of the pre-Islamic past to be idolatrous, there was also a vibrant tradition showing great positive interest in monuments like the Pyramids, one that began to change in the time of Muhammad Ali into modern nationalist interest. But this interest was commonly ignored by Europeans and Americans. Westerners spread stories, often demonstrably false, that local residents throughout the region destroyed ancient monuments and statues in order to find gold inside. When Muhammad Ali instituted a groundbreaking antiquities decree in 1835, prohibiting the exportation of antiquities out of the country, Europeans dismissed it and questioned the pasha's motives. "Not satisfied with those [monopolies] he has established on the living," Muhammad Ali "has lately introduced one also in the kingdom of the dead," the London Morning Post declared. "He is even said to have expressed his readiness to part with the pyramids, provided a competent price be offered."

The reality is also that European interest in the past — generally excluding interest in the present — was often very destructive. "Unfortunately for [Egypt]," Enfantin lamented, "its temples, its mummies, its pyramidal souvenirs are still too living, because all our illustrious travelers, literate and lovely connoisseurs, are arrested with the pharaohs on the Nile, without speaking to the fellahin." Egypt was beset with rapacious collectors and scholars, with little boundary between the two: Egyptologist Gardner Wilkinson remodeled an ancient tomb for a house while working at ancient Thebes, Orientalist Edward William Lane a tomb at Giza. Both burned mummy cases for heat and cooking fire. Circus strongman turned tomb raider Giovanni Belzoni openly declared his goal "to rob the Egyptians of their papyri" — texts that he found among mummy wrappings. Champollion, the celebrated decipherer of hieroglyphics, proudly ripped an inscription out of the wall of a temple to bring it to the Louvre. All of this activity was in the name of "saving" the past for the "civilized world."

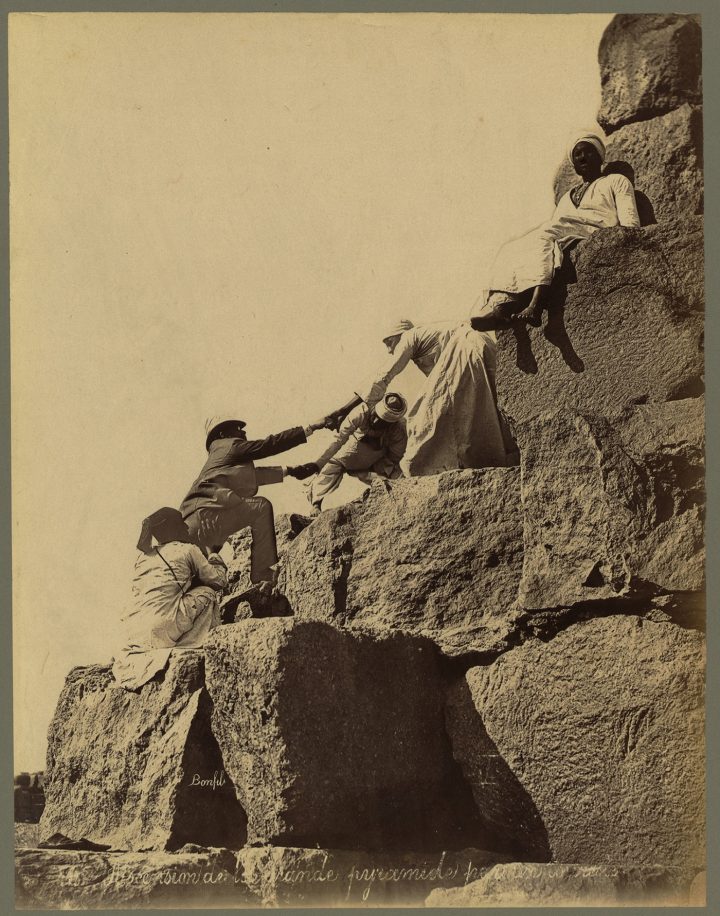

Europeans used their supposedly superior knowledge of the Egyptian past, along with their knowledge of its present, as a means of control — both of antiquities and of the country. The Pyramids have been a popular site for European and American performances to demonstrate such control. This control is symbolized quite dramatically by the previously popular tourist act (now prohibited) of climbing the Pyramids. Doing so was a form of conquest, like conquering a mountain, and the tops of the pyramids afforded a nearly godlike view of the surroundings. And all of this, quite literally, was on the shoulders and backs of Egyptians: tourists and explorers would hire members of a Bedouin tribe that lived nearby to help them climb.

The Pyramids afforded a backdrop for demonstrating superior knowledge, too. For the future American Jewish community leader Cyrus Adler, this meant talking with the Bedouins at the Pyramids. He wrote home to his mother that he got into an argument with one about grammar, which the sheikh of the tribe heard and settled in favor of Adler. Nearly half a century later, Adler still saw fit to include the story of how he knew Arabic better than the Arabs at the Pyramids in his memoirs, where he recounts a series of tales that emphasize or even exaggerate his own importance.

In the present case we see all of this clearly. Linant both knows more about the Pyramids — besides conducting a detailed study, in some versions he has to explain to the pasha they were constructed from the bottom up — and cares more about them. Muhammad Ali is portrayed as ignorant, even an animal. Linant declared that the pasha, in his supposed lack of interest in the ancient monuments of Egypt, remained a "mere rude Turk" his entire life. We hear that Linant knew how to deal with Muhammad Ali "as an Irishman knows how to persuade a pig to move in the right direction." Especially imaginative is the version told by Edwin De Leon, American consul to Egypt in the 1850s before becoming a Confederate diplomat. In De Leon's telling, the pasha growls, and perceives Linant's statistics like indecipherable "cabalistic figures." Pointedly, De Leon even has him impatiently brush aside Linant's report by asking "What do I know about your hieroglyphics?"

Perhaps Linant was performing, too. As it turns out, he wasn't even the only Frenchman to be credited as the savior of the Pyramids in this incident. The newspaper and journal accounts of the time, which all fail to mention Linant's role, widely credit his countryman, the French consul to Egypt, Jean-François Mimaut. Mimaut was said to have achieved this, improbably enough, by writing a letter. But this was no ordinary letter. It was printed, in extract or its entirety, in newspapers and academic journals throughout France and beyond. Le Mercure de France hailed it as having "a poetry and character worthy of ancient times." For the Journal des Artistes, it was "a sort of masterpiece of reason, eloquence, and propriety; there is neither a word to add, nor a word to remove."

Mimaut's actions were regarded in the context of France's work in saving and studying antiquities over the previous 40 years, since Napoleon's expedition to Egypt — an expedition, we must remember, that was, above all, an imperialist venture. French writers praised their country's achievements as the "intellectual conquest" of Egypt. "If Africa becomes humanized, if civilization ever flourishes again on its shores, where the monuments of Roman grandeur lie," ran one French article praising Mimaut's letter, "the glory must come back to France which, since the expedition to Egypt, has pursued this honorable mission." Napoleon's expedition was and still is seen in Western eyes as a watershed in scholarly understanding of ancient Egypt and respect for its past; but Egyptians had a very different view. The Cairo scholar al-Jabarti admired the great learning of the French, but he also described the destructiveness of Napoleon's army in Cairo: they demolished tombs, shrines, and palaces, and damaged the great al-Azhar mosque.

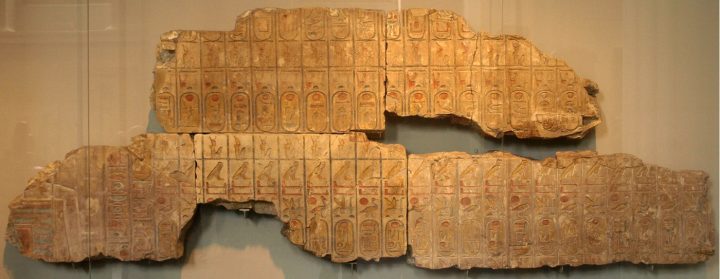

Was Mimaut a hero? Just four months after writing his letter, he was on a ship bound for France with the collection of hundreds of antiquities that he had looted from Egypt while he served as French consul. Mimaut proudly insisted that he did not acquire the collection but dug it up himself, the product of "seven years of sacrifices." And the French public appreciated those sacrifices, praising his collection as "an epoch in the annals of science." The collection was put on sale after Mimaut's death the following year. Among the notable items was the Abydos Table, an important list of kings ripped out of the walls of a temple. (Mimaut insisted he was not responsible, but that it had been removed by "barbaric hands" and then "disappeared," though he never specified how it reappeared.) It was purchased by the British Museum. The catalogue of the collection produced at the time was prefaced with a laudatory biographical note … and the full text of the famous letter. Throughout, the habitual looter and collector Mimaut was remembered as a savior of antiquities.

Plus ça change …

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment