https://www.yahoo.com/travel/the-first-worst-tourist-a-3000-year-old-travel-129230521682.html

The First Worst Tourist: A 3000-Year-Old Travel Tale

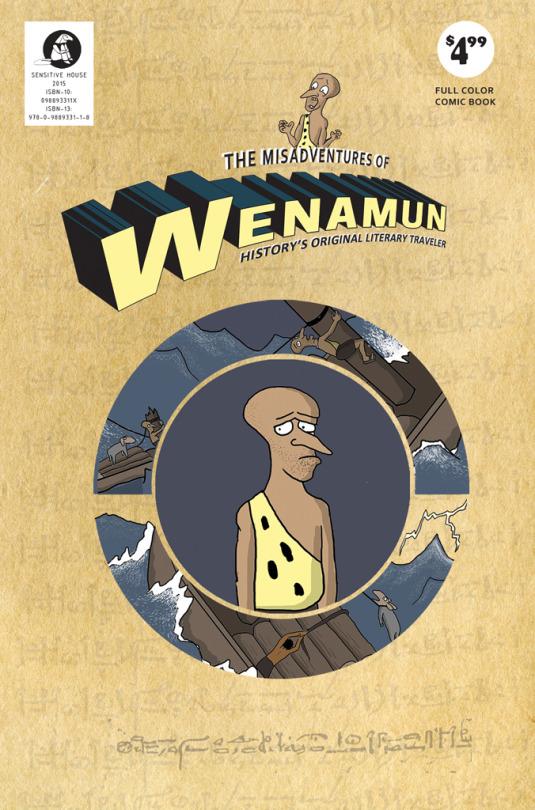

The author’s comic book. (Photo: Courtesy of Rolf Potts)

When

compared to Odysseus or Herodotus, Wenamun doesn’t seem like much of a

traveler — at least not by the heroic standards of ancient literature.

In the papyrus tale that bears his name, Wenamun, an inept Egyptian

priest who journeyed across the eastern Mediterranean to acquire

Lebanese lumber more than 3000 years ago, does not come off as a leader

of men. He doesn’t discover new lands, nor does he outwit sea monsters,

or even offer any hard-won insights into the cultures he visits. For the

most part, the ancient Egyptian sojourner makes one boneheaded travel

blunder after another.

In

Lower Egypt, for instance, Wenamun misplaces his priestly letter of

introduction (the Ramses XI-era equivalent of losing his passport), a

gaffe that catches up with him later in the journey. Along the Levantine

coast, in the port city of Dor, his gold and silver gets stolen by one

of his own sailors. And, after a series of humiliating fiascoes stemming

from an ill-considered display of arrogance toward his Lebanese hosts,

he ultimately breaks down weeping and yearns to go home.

From the comic book. (Photo: Courtesy of Rolf Potts)

Far

from an intrepid adventurer, Wenamun is for all appearances as hapless

as any modern tourist — and that is exactly what makes him fascinating.

“To me the tale of Wenamun is great because it gives a vivid, first-hand

sense of the frequent tedium and difficulties of most travel in ancient

times,” says T.G. Wilfong, a professor of Egyptology at the University

of Michigan. “The story gives us a vivid picture of Egypt and its ambiguous place in the ancient Mediterranean world at the time.”

When I first read a summary of Wenamun’s journey in Lionel Casson’s Travel in the Ancient World

a few years ago, I was struck by two things: First, that an ancient

travel tale could be so self-deprecatingly goofy; and second, that I’d

never heard of it before, even after years of reading and writing about

travel. Familiar as I was with ancient epics that featured supernatural

heroism, uncommon bravery, and military conquest, I was surprised — and

delighted — to find a travel protagonist so foolish and fallible and,

well, relatable.

Why

is it, I wondered, that most modern readers had never heard of Wenamun?

It could have been because his travel tale is episodic and fragmentary,

and doesn’t feature a concrete ending. It could also have been due to

the fact that the tale was lost to history until the late 19th century,

when it was discovered by Russian Egyptologists (whose work was

underreported in the Anglophone world).

As

much as anything, however, the story of Wenamun has likely been

overlooked because it doesn’t flatter the reader with a

self-congratulatory vision of cultural heroism. Written at a time when

Egyptian power in the eastern Mediterranean region was on the wane, it

has a decidedly postcolonial tone, lampooning (rather than glorifying)

the deeds of its peripatetic protagonist.

The author and illustrator (Photo: Luke Van Tassel)

After

reading various translations of the story, I sensed that modern

audiences might better appreciate the cadences and twists of this tale

if it were retold, in more fanciful form — not as a scholarly document,

but as a comic book. This in mind, I transformed the story into graphic

narrative with the help of my teenaged nephew Cedar Van Tassel, an

up-and-coming comics blogger whose youthful sensibilities lent the right amount of whimsy and impetuousness to the tale’s bumbling anti-hero.

Staying

as true as possible to the translated papyrus, we broke the tale down

into a series of panels that Cedar fleshed out in hand-drawn narrative,

first in pencil and later in ink. We called it The Misadventures of Wenamun, and a black-and-white version of the comic debuted online at The Common early last year.

Some

of the earliest fans of the comic were scholars at Oxford University’s

Griffith Institute, who used social media to share the tale with

far-flung Egyptology students and scholars. “The comic version

definitely made the story more vivid and enjoyable for me,” notes Brown

University grad student Christian Casey, who found the graphic narrative

via Facebook. “I’m a comic book nerd, and I always search the boxes at

conventions for Egypt themed comic books. So the Wenamun comic was right

up my alley.”

Earlier last year, Sensitive House Press proposed reimagining “The Misadventures of Wenamun” as a full-color comic book, with a design and feel not unlike an old postwar issue of Amazing Stories.

Aimed at comic-book fans, history buffs, armchair travelers, and

students of all ages, it debuts this month in select bookstores and is

available for online order. (All profits from the sale of the Wenamun comic are earmarked for Save the Children’s Syrian refugee initiative).

Perhaps

in time the story of Wenamun’s Egypt-to-Lebanon misadventure will be

more widely recognized for its humble contribution to the canon of

ancient travel literature. It feels fitting — if only as a cautionary

tale — in an age when the first step to meaningful travel can be

admitting to our own shortcomings as cross-cultural wanderers. “The tale

of Wenamun is one of the most accessible stories from ancient Egypt,”

says Wilfong, “a rare case when we really feel like an ancient Egyptian

is speaking directly to us.”

No comments:

Post a Comment