https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/what-bread-did-ancient-egyptians-eat

How the Man Who Invented Xbox Baked a 4,500-Year-Old Egyptian Sourdough

It took three experts, two museums, and one clay pot to bake a truly ancient loaf.

Like many of us, Seamus Blackley tweeted a photo of homemade sourdough while stuck at home this weekend. Unlike many of us, however, Blackley is no novice, and this was no online recipe comprised of everyday ingredients. A trained physicist and video game producer credited with inventing the Xbox, Blackley is also an experienced baker and amateur Egyptologist. The recipe came, in part, from ancient hieroglyphs, and the ingredients came, in part, from museum archives.

Blackley's weekend sourdough was the culmination of a year-long passion project that produced a loaf of bread not eaten for millenia. By extracting 4,500-year-old dormant yeast samples from ancient Egyptian baking vessels and reviving them in his home kitchen, Blackley and his collaborators quite literally brought history to life, and ate it. "It was unbelievably emotional for me," says Blackley. "I stan Egypt." While the breakthrough is cause for celebration among Egyptophiles, archaeologists, and bakers everywhere, the project was actually born of an online blunder.

Ever since he first saw a mummy on Scooby-Doo as a child, Blackley has harbored an insatiable curiosity for all things Egypt. And ever since his parents let him in the kitchen as a teenager, he's been baking bread as well. So when a friend approached him last April with what he claimed was ancient Egyptian yeast, Blackley leapt at the opportunity, tweeting a photo of the resultant "ancient" loaf. Online academics summarily dragged him for the yeast's questionable provenance.

One of the detractors was an archaeologist with a background in Egyptology from the University of Queensland, Dr. Serena Love. "I was like, 'Who is this guy?' I don't have an Xbox, I could care less about Xboxes," says Dr. Love. She expertly probed him about the yeast, asking what Blackley ultimately called "the right questions." Another interested voice was Richard Bowman, a biologist at the University of Iowa.

"I hadn't exactly done my homework," says Blackley. "They weren't trolling me—I'm from the games business, I'm immune to trolling at this point. They were just after the proof. I was really embarrassed I hadn't done this right."

The online reaction actually seemed to encourage Blackley. "I feel I have a responsibility of being a modern representative of ancient Egyptians and not letting people give them any shit," says Blackley. He'd hoped his experiment would disprove all-too-common assumptions about ancient cultures.

"People assume they were primitive because they didn't have iPhones," says Blackley. "They were potentially more sophisticated because of that." He believes that feeble attempts at ancient-baking reenactments further denigrate the legacy of ancient Egyptians as well. "People come out with a bad result and say, 'Oh, look at this disgusting food, the ancient world must have been terrible,' but anyone who's studied this knows that's utter bullshit," says Blackley. "They were master bakers."

Instead of arguing with his auditors, Blackley enlisted Love and Bowman to help him get it right and bake a truly ancient Egyptian loaf. "I picked the two people who gave me the most crap and I said, 'Let's be friends,'" says Blackley.

Between an archaeologist, a biologist, and a dedicated, well-funded baker, the team laid their groundwork. If Dr. Love could secure access to ancient baking pottery, Bowman could provide a safe method to extract the ancient yeast for Blackley to then revive and bake. "It was one of those weird confluences where the right people with the right mix of skills showed up on Twitter at the same time," says Blackley.

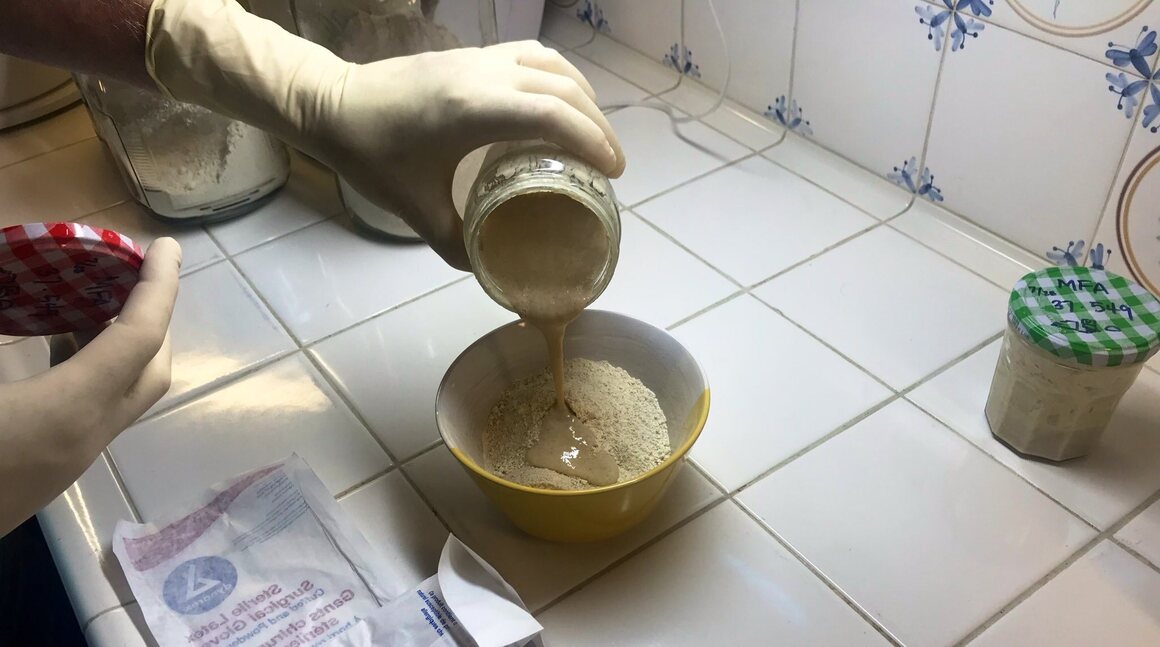

Dr. Love contacted several museums throughout the United States and Europe with Ancient Egypt collections and requested access to their archives. "I definitely received mixed responses," says Dr. Love. "A lot of people ignored me." Finally, Boston's Museum of Fine Arts and Harvard's Peabody Museum relented, allowing Blackley access to their deep troves of ancient Egyptian artifacts. "It was a little intimidating, to be honest," he says. Bowman's non-invasive extraction method resembles miniaturized fracking, wherein a portion of ceramic is injected with a nutrient bath before being pulled out through a syringe with the ancient yeast intact.

Blackley shipped the samples to Bowman in Iowa, but took one vial home to Southern California to feed and propagate himself. Interestingly, the sample could only be revived with Emmer flour, a denser varietal of flour likely used by Egyptians of the Old Kingdom. Modern growth media consistently killed the yeast samples in Bowman's lab in Iowa as well, leading them both to a similar conclusion: In the off-chance that the samples were contaminated, the microbes are still likely thousands of years old.

Blackley revived the yeast and baked it on a pan in his conventional home oven, resulting in a loaf that made headlines this past August. "I've made a fuck ton of sourdough," says Blackley, "but this was different." The ancient loaves were sweeter and chewier than the standard modern sourdough, with a smooth crumb closer to white bread.

For a truly ancient loaf, however, Blackley would have to bake like an Egyptian.

According to Dr. Love, commoner foods of the Old Kingdom included beer, pulses, and onions ("they were much sweeter than ours, you could eat them like apples," she says), but nothing was more ubiquitous than bread. Blackley, having studied hieroglyphics, says ancient Egyptians actually had 176 words for it. If they were big on baking, however, they were less insistent on clear recipes, relying mostly on oral transmission of instructions. As such, Dr. Love had to synthesize data from ancient art, writing, and archaeology to decode their baking methods.

Her work showed that Egyptians placed their dough into a heated, conical, clay pot called a bedja before burying it in a hole surrounded by hot embers, a process Blackley made it his mission to reenact to perfection. "The guy's mind runs at 100 miles per hour," says Dr. Love, "but he's very methodical. I knew it would work."

First, Blackley spent months baking ancient sourdough in his home oven using a tajine as a stand in for a bedja. Staying true to the yeast's forebears, he even fermented all his yeast at exactly 94° F. "That's the average daytime temperature around the Nile, and it makes bangin' bread," says Blackley.

He estimates that he cooked about 75 loaves before building his own bedja by hand and digging a hole in his backyard to master underground baking. "If I hadn't spent so much time working on it, it would have been a wreck," says Blackley. "I would have been another one of those people posting a shitty, burned, flat loaf saying, 'Welp I guess this is what the ancient Egyptians had to deal with!'" Instead, Blackley's backyard loaf proved exceptional, if not for one minor hiccup. "I was freaking out because I burned the top," says Blackley. "But in the end, I realized the process of figuring out how to bake like them was really what got me so close to these people I respect so much, not the end product." From the ancient yeast to the underground baking method, Blackley had at long last produced an indisputably ancient loaf with the same rich sweetness as his summer sourdough.

For now, Bowman continues to sequence the extracted samples in his lab, separating ancient yeast from modern contaminants. Dr. Love plans on gathering a greater diversity of yeast samples from an array of Egyptian artifacts. And Blackley fantasizes about one day selling ancient Egyptian bread commercially.

Once the sequencing is completed, the team has agreed to return the isolated ancient yeast to Egypt in one form or another. "It's their property," says Dr. Love. In the meantime, Blackley is digging more holes in his backyard.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world's most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment