From ancient Egypt to the Maghreb

David Tresilian , Tuesday 2 Nov 2021

A new exhibition draws attention to the use of papyrus as a writing material in ancient Egypt, arguing that it was the country's single greatest invention, while a slightly older one brings together recent titles in French on the Arab Maghreb, writes David Tresilian

Asked to name the greatest inventions of the ancient Egyptians, many people might point to their architecture, with ancient Egypt's stone-built monuments, the oldest in the world on a comparable scale, producing awe in visitors to Egypt in antiquity as they still do today.

They might point to ancient Egypt's hieroglyphic writing system, a source of wonder in antiquity and of puzzlement over subsequent millennia until finally deciphered at the beginning of the 19th century. Or they might cite its art and religion, apparently untouched by influences from outside Egypt and immediately recognisable as important expressions of ancient Egyptian civilisation.

How many, though, would choose the pith of the stems of the papyrus plant when cut into strips and stuck together as a writing material as an invention of comparable importance? Perhaps the answer is only a very few, but if so then the vast majority of people are mistaken, at least according to a new exhibition. This makes a compelling case for considering the development of a writing material from papyrus as arguably ancient Egypt's greatest invention.

The exhibition, which opened at the Collège de France in Paris last month and runs until the end of October, reminds visitors of some of the reasons why papyrus when used as a writing material was so important both in ancient Egypt and beyond. Other civilisations of comparable antiquity developed writing systems for their languages as the ancient Egyptians did for theirs in the shape of the hieroglyphic and demotic scripts. They also identified various materials that could be used to record texts and documents.

The ancient Assyrians and Babylonians used clay tablets, which when baked or dried in the sun could be used to preserve written records. Other civilisations used pieces of clay or stone, animal skins, or even bones or bark as writing materials. The Romans used wooden tablets coated in wax. However, all these materials had disadvantages. Some were restricted in size, meaning that not very much text could be recorded on them, while others, among them clay tablets, were bulky, difficult to store, and could not be reused once fired.

What was needed was a writing material that was cheap to produce from plentiful raw materials, easy to write on using pen and ink, flexible and possible to produce in large sheets or rolls if necessary, easy to store, and having, in Egypt's climate at least, excellent storage properties. These criteria were met by sheets made from the stems of the papyrus plant, a kind of wetland sedge then common in Egypt, and they served to record the bureaucratic and other documents necessary for the development of an increasingly centralised and sophisticated state.

The oldest papyrus documents that have come down to us date back to the ancient Egyptian Old Kingdom (c 2575-2150 BCE), with the exhibition pointing in particular to one, discovered only in 2013 at Wadi Al-Jarf on the Red Sea, that records the delivery of stone for use in the building of the Pyramids. However, it seems that during both the Old and New Kingdoms (c 1539-1075 BCE) reading and writing were relatively restricted skills, being largely monopolised by specialised scribes. Writing had not yet spread to the wider population, and written texts, as well as the ability to read them, were still invested with a certain mystique.

All this began to change with the advent of Greek (Ptolemaic) rule in Egypt after the conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE. According to the exhibition, while papyrus was an ancient Egyptian invention, it was the country's later Greek rulers who were responsible for turning it into something like a mass medium.

According to exhibition curator Jean-Luc Fournet, himself a professor at the Collège de France, while some 2,000 papyrus documents are known from Egypt from the period between the Old Kingdom Pharaoh Cheops, the builder of the Great Pyramid, and the arrival of Alexander the Great, this number increases to some 55,000 for the subsequent Ptolemaic period that have been published by scholars. Even this number represents only some 10 to 20 per cent of the total number that have been discovered.

Papyrus scrolls were used for copies of ancient Egyptian religious texts, otherwise only appearing on the walls of tombs, among them the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead. Stone tablets or the walls of buildings could also be used for these, like the famous Rosetta Stone, a stone slab or stela bearing an official inscription in three different scripts that is now in the British Museum in London. All visitors to ancient Egyptian temples will be familiar with the habit of covering the walls of public buildings with written inscriptions.

But such stone-supported writing could only be used for certain purposes, and its drawbacks are obvious. Papyrus scrolls, on the other hand, could be transported long distances, were comparatively easy to use, were durable, and could be easily labelled and stored. Individual sheets of papyrus could be used for the more mundane purposes familiar from the often still largely paper-based bureaucracies of today.

The ancient Egyptians also used papyrus for the records of everyday life, from court records to commercial receipts and civic and legal documents to private letters and school exercises, each written in whichever language and script seemed most appropriate. Hieroglyphics were used for religious or literary texts and the demotic Egyptian script for everyday documents and records.

Greek and Latin were used when the country came under first Greek and then Roman rule following the defeat of ancient Egypt's last Ptolemaic ruler Cleopatra VII at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE.

TRANSMISSION: One main reason why all this is so important, the exhibition says, is that without papyrus probably all, or almost all, of the written heritage of antiquity would have been lost, including that of ancient Greece and Rome.

Without papyrus, we would not now be able to read the works of the ancient Greek philosophers or the Latin poets, since their works would originally have circulated on papyrus scrolls.

While the earliest copies of such materials that have survived from antiquity are generally written on parchment, a kind of animal skin, or, somewhat later, on wood or rag-based paper, these materials were only introduced from the second century BCE, in the case of parchment, and as late as the 13th century CE in Europe, in the case of paper, and any copies made on them of earlier texts would have been copied from papyrus originals.

Even with parchment being more widely used in the late Hellenistic and Roman periods, there is still every reason to believe that the holdings of the famous Library of Alexandria would have been made up of papyrus scrolls. This means that during the crucial centuries between the composition of the ancient texts and the more general use of parchment or paper, almost the only way that irreplaceable works could have been read and stored was on papyrus.

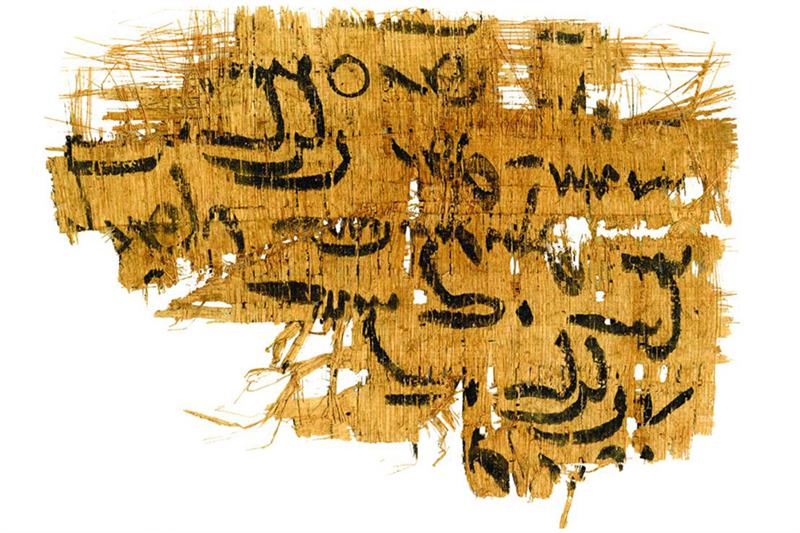

Such reflections are likely to make visitors to the exhibition view the papyrus plant and the writing material made out of it with new respect, even if to modern eyes the writing surface can appear rough and irregular in quality. As if anticipating such reservations, the exhibition displays a range of original documents on papyrus, most of them taken from French collections, notably the Institut de Papyrologie of the neighbouring Paris university the Sorbonne, showing the ways the material was used in antiquity and even as late as the early Middle Ages in Europe.

There are receipts with details of commercial transactions recorded on them, for example. One such receipt, dated to the reign of Cleopatra VII and thus to Egypt's last Ptolemaic ruler, records a sale of wheat by a man named Ptolemaius to another called Antiphilos and is written in Greek. A later example of an administrative document is a papyrus from the office of Qurra ibn Sharik, Egypt's then Arab governor and written in Arabic and dated 709 CE, instructing a certain Basile to provide high-quality bread for his soldiers. Basile, presumably a Greek speaker, would almost certainly have required a translator.

There is an estimate for a water project from 259 BCE, the record of a court case from 350 CE, and a copy of part of the Homeric poem the Odyssey, apparently done by a student, made in Fayoum between 250 and 200 BCE. There is also a fragment from a play by the ancient Greek author Menander, the earliest ancient copies of whose works only exist on papyrus, from 225 BCE.

Very few papyrus documents have survived from Europe or locations outside Egypt because the wetter climate meant that the papyrus rotted and documents written on it were not preserved as they often were in Egypt. However, there seems little doubt that Roman libraries would have consisted largely of papyrus scrolls, and a complete private library of such scrolls was discovered in the remains of a villa at the ancient site of Herculaneum on the Bay of Naples in the 18th century. Unfortunately, it was deeply buried in ash and its contents had carbonised during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.

The exhibition also includes official documents sent in the name of the Byzantine emperor Theodosius II to Elephantine in Upper Egypt between 436 and 450 CE and from the later emperor Michael II dated to between 820 and 829 CE. There are various documents on papyrus preserved from the northern Italian city of Ravenna, capital of the Western Roman Empire after the fall of Rome itself, some early bulls (religious decrees) issued by Roman Catholic popes, and a series of documents made in the name of France's Merovingian kings between 625 and 679 CE all similarly written on papyrus.

A nice final touch is that the exhibition includes some planters full of genuine papyrus. The plant itself, plentiful in Egypt in antiquity but then largely dying out, has since been re-introduced from Sudan where it continues to flourish. Some visitors to the exhibition may find themselves realising that they have never actually seen papyrus plants in the flesh despite their familiarity with their pith as a writing material.

The Paris exhibition helpfully gives them the opportunity to do so. For residents or visitors to Cairo, the Dr Ragab Papyrus Institute and Pharaonic Village in Giza also provides many examples of the plants, along with demonstrations of how they can be made into a writing material.

Le Papyrus dans tous ses états, Collège de France, Paris, until 26 October.

This year's Maghreb des Livres book fair in Paris found a novel solution to the problem of how to hold a public event of this sort while still respecting the Covid-19 restrictions that, though relaxed, are still in force in France.

In order to cut interaction to the minimum and prevent the public handling of books, there were no books at this year's book fair — seemingly an overly dramatic solution until one remembers the other activities for which the Maghreb des Livres has established itself on the Paris calendar, including lectures, readings, and discussions of the year's crop of books published in France relating to the Arab Maghreb countries of Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco.

As a result, while the absence of books would have been missed by all attending this year's fair, held over the weekend of 10-11 July in the gilded 19th-century splendour of the Paris Town Hall, there was still a rewarding programme of discussions to inform the public of at least some of the books that have appeared in French on aspects of the Maghreb this year.

In previous editions, the fair has overflowed from the Town Hall's first-floor function rooms into subterranean committee rooms and other areas of this evocative building, a replica of the original burned down in the 1870 Paris Commune. This year, discussions took place on a smaller scale, and for those not able to attend there were also live transmissions of some of them on Facebook. The fair had also been rebaptised the Maghreb-Orient des Livres in order to signal some Middle Eastern content.

As is so often the case with events of this sort, even for the most committed audience members it was not possible to attend every discussion, talk, or lecture owing to various overlaps. But from those that Al-Ahram Weekly was able to attend over the two-day fair, perhaps certain themes stood out, even if these were presumably accidental, not having been programmed by the invited authors or their publishers in advance.

One such theme was memory, a fashionable theme at present across a range of subject areas and not only in relation to the Maghreb. Participants at this year's fair thus discussed what and who has been remembered from the generally quite recent past and the purposes for which this has or has not been done, looking particularly at issues surrounding the memory in France of the Algerian War of Independence in the 1950s and of the 2011 Arab Spring revolutions.

Speaking at a panel discussion on the fair's first day, French-Tunisian writers Hella Feki, Saber Mansouri, and Hatem Nafti talked about Tunisia 10 years after the removal of former president Zein Al-Abidine bin Ali in the country's Jasmine Revolution. Feki and Mansouri are Tunisian novelists writing in French, and in their books Noces de jasmin and Sept morts audacieux et un poète assis, both published in 2021, they had sought to reconstruct the events of ten years ago in imaginative form through the eyes of ordinary people.

One thing fiction could do, Feki said, when compared to other forms of writing, was to connect individual experiences to historic events, helping to fill out the forms of emotion felt by people at the time. In her novel, she had aimed to communicate something of the hopes of the time to the reader, Feki said, even after a 10-year period following the fall of the Bin Ali regime that had been marked by a certain amount of confusion and disillusion.

Nafti, a journalist and commentator, explained that he had been an adolescent during the Tunisian Revolution, perhaps one of the young people who had filled the streets of Tunis and other cities across the country to demand the fall of the regime. One of the issues in Tunisia now, he said, drawing on arguments presented in his De la Révolution à la restauration, published in 2021, was that while there were many economic and other problems facing particularly young people in Tunisia today, there was not the same "obvious target" for popular anger as there had been in the last days of the Bin Ali regime.

Earlier in the day, panelists at a session on "writing about Beirut" had also sought to connect past and present, in this case with memories of the Lebanese Civil War in the 1970s and 1980s connecting with the present economic crisis in Lebanon in the writings of Lebanese authors writing in French and resident in Paris.

The session temporarily extended the focus of the fair from Maghreb to Mashraq and from Tunis to Beirut, but in the works of these four authors, Lamia Ziade on her Mon Port de Beyrouth, Hyam Yared on Nos longues années en tant que filles, Camille Ammoun on Octobre Liban, and Sabyl Ghoussoub on Beyrouth entre parenthèses, there was a similar focus on how to write about the city's complex present, while aiming to make sense of it in relation to the past.

However, memories from Algeria provided the lion's share of reflections on this theme, with a panel discussion on the fair's second day bringing together French writers on Algeria to consider ways in which questions relating to Algerian memory are today being approached in France. French historian Benjamin Stora, author of a widely discussed French government report on relations between France and Algeria (France-Algérie, les passions douloureuses), spoke interestingly on the background to this report, commissioned by French president Emmanuel Macron, on what memory could do in clearing the way to a better future.

Tramor Quemeneur, author of La guerre d'Algérie revisitée, nouvelles générations, nouveaux regards, gave an expert overview of debates about memories of the Algerian War of Independence, suggesting that "silence" and "forgetting," at least on the French side, were now giving way to more productive forms of remembering, because focused on "small steps" and concrete initiatives, some of them related specifically to the younger generations, that could help to lift the burden of the past.

OTHER THEMES: Two other themes that cut across discussions at this year's fair had to do with France's relations to the Maghreb countries today and the role particularly of young people in helping to move forward in improving or even transforming them.

In a session on "40 years of difficult relations between the French Republic and Islam in France," the participants, each the author of a recent book bearing on the topic, discussed some of the problems or misconceptions that may have arisen in recent years. According to French author Agnès de Féo, author of Derrière le niqab, there has been an increase in the number of women of Muslim background choosing to wear the niqab, or full face veil, in France, with this raising certain legal questions after the passage of legislation designed to ban full face coverings in public places in the country.

For French academic Raberh Achi, speaking on the same panel, it was important to take a historical approach to present issues, looking back over the course of a century at administrative traditions between the state and Islam and other religions in France. One of the things that could be done as a matter of urgency, Achi said, was to improve the provision of Arabic classes in French schools. Though there was considerable demand for such classes among French young people of Maghreb descent in France, he commented, the state education system had not always been agile enough to respond, causing some to take refuge in the private sector and French young people as a whole to be denied the opportunity to learn Arabic and more about Arab civilisation in schools.

One of the things that this year's Maghreb des Livres was unable to do was to give a sense of the overall production of books and other written materials, fiction or non-fiction, written in French on the Maghreb this year. It is to be hoped that at next year's event, with Covid-19 restrictions lifted, visitors to the fair will be able to enjoy browsing through the stands of the different French publishers that maintain Maghreb lists, as has been the case in previous years.

However, perhaps just as importantly, it is also to be hoped that the fair will be able to reach out to publishers based in Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco in ways that it has not always been able to do in the past, bringing their representatives to Paris such that French audiences are able not only to gain a sense of books published in France on the Maghreb, but also books published in French in these countries themselves. This would undoubtedly help to complete the panorama provided by what currently is the only French event dedicated to French-language Maghreb publishing.

Similarly, while in previous years there have been attempts at the Maghreb des Livres to provide a sample of literary and other publishing in Arabic in the Maghreb countries, this has often seemed to present additional difficulties. However, there seems to be no real reason, apart perhaps from economic, for Maghreb Arabic-language publishers not to be present at the fair, since not only are many of those who regularly attend competent in both French and Arabic, but also it would give even monolingual visitors a keener sense of the connections between the parallel linguistic productions of the different Maghreb countries.

In the meantime, this year's fair was also marked by a third major theme, which was the impact of young people in contributing to, and perhaps also shaking up, the French-Maghreb publishing industry. Speaking at a session on "writing about the banlieue", a group of young French authors of various backgrounds described their experiences of writing about the popular city districts in which they had grown up.

One came away with a sense of the range of genres and sometimes pressing questions being attempted by these authors, who included Seham Boutata for La mélancolie du maknine, Abdoulaye Sissoko for Quartier de combat, les enfants du 19ème, Adnane Tragha for Cité Gagarine, on a grandi ensemble, and Rachid Santaki for Laisse pas trainer ton fils.

Elsewhere, another group of young people, this time slightly older and more settled in sometimes international careers, spoke on questions of diversity in the French media. There might be problems, moderator of the session Nadia Henni-Moulai suggested, in the range of experiences covered in the French media, as well as in the absence of people from different backgrounds covering them.

For Walid Hajar Rachedi, founder of the French alternative media site Frictions, the problem went deeper since it could not be treated only by including "token" or "cosmetic" stories about non-mainstream experience on terrestrial TV channels. There was also a need for access to financing, for the broadening of existing business models, and for alternative media to find mainstream audiences and the advertising revenues and other financing that went with them.

Karim Baouz, a journalist with French television as well as various international channels, said that minority communities in France, like elsewhere, could produce grassroots media that reflected their experiences and communities, often on a small-scale or even volunteer basis. Even so, he admitted that this left problems in the mainstream media untouched and for the most part could continue to shut young people from minority backgrounds out of sometimes lucrative media careers.

Le Maghreb Orient des Livres, 10-11 July, Paris.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 4 November, 2021 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment