https://hyperallergic.com/469915/when-will-egyptian-and-peruvian-mummies-return-home/

When Will Egyptian and Peruvian Mummies Return Home?

In the context of the Field Museum's lack of information regarding their provenance the mummies' return to the Field Museum after a three-year tour is hardly a homecoming.

In March, the Field Museum opened a new exhibition titled Mummies, showcasing examples from its own collection of mummies from Egypt and Peru. It started its life in 2015 as a touring exhibition under the name Mummies: New Secrets from the Tombs, returning from its last stop at the American Museum of Natural History after three years on the road. "The exhibition is arriving back home after traveling across the country, just in time for the Museum's 125th anniversary," the exhibition press release proudly announces.

We're all probably pretty familiar with mummy displays. Consistently popular, and consistent moneymakers, they never go out of style at museums. What sets the Field Museum exhibition apart is the comparison of mummies from the two places where active mummification was practiced in the past. Since Egyptian mummies are much more familiar to the popular imagination, it's good to see the Peruvian examples alongside them. The similarities and differences are well highlighted: We learn, for instance, that the practice of mummification in Peru is much older, going back roughly 7,000 years. And we see not just differences in place, but in time as well. The exhibition is very successful in showing changes in Egyptian practices of mummification over time, stretching some 3,000 years from the Predynastic Period to Egypt's incorporation into the Roman Empire.

Other aspects of the exhibition may be more typical, though these too are generally executed well. At one point we see a recreation of a 26th Dynasty Egyptian tomb (c. 600 BCE), to provide a context for the placement of mummies; at another, we see an Egyptian coffin with its lid removed, allowing us to observe details of construction as well as drawings on the inside. All the while, mood music meant to inspire awe and wonder plays, though perhaps it's also a little creepy.

One of the main themes running through the exhibition seems to be the juxtaposition of the distant past with the modern present. The museum's press release emphasizes "cutting-edge technology," and we encounter it throughout. CT scans are placed alongside the mummies to reveal what lies beneath the wrappings. Their importance is highlighted by the prominent placement of a scanner (donated by GE) with a model mummy in the opening room of the exhibition. Interactive touch screens allow for 3D manipulation of mummies — one each from Egypt and Peru. The 3D-printed replicas give a vital sense of feel for objects we would otherwise not be allowed to touch.

But as an archaeologist and a museumgoer, there were a couple of topics where I was left wishing for more information.

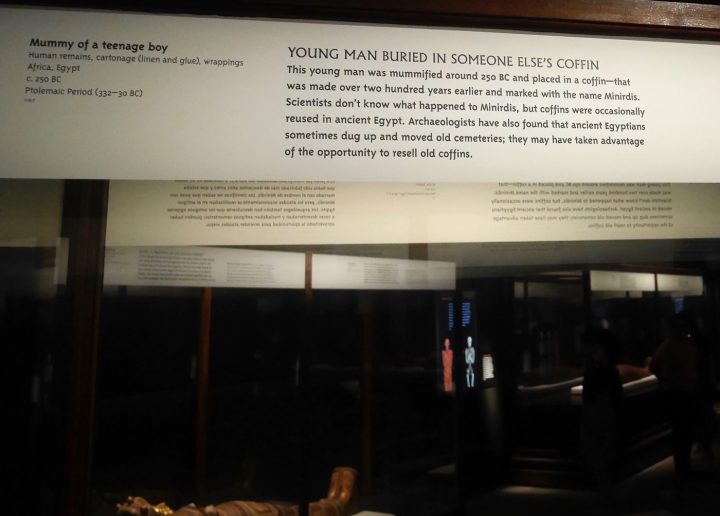

One of the things that becomes apparent, if you pay close attention to the labels, is that most of the objects — and all of the mummies — lack provenance. Some items on display list a specific site of origin, but most simply give the place of origin as "Egypt" or "Peru." This leads to some natural questions: Where did they come from, and how did they get to the Field Museum?

These questions aren't answered in the exhibition itself, but in the museum's regular ancient Egypt gallery we learn that much of the Egyptian material was purchased in 1894 by Edward Ayer, the museum's first president. This is confirmed by a statement from the museum provided to Mental Floss in 2017. According to that statement, the Egyptian mummies came from the site of Akhmim. However, since we can only trace them to the point of purchase (Ayer would have bought them from a dealer), neither Ayer nor anyone else could ever confirm this claimed origin. So, it is not surprising that the museum displays list the objects' provenance as simply "Egypt."

Date and place of purchase matter for many reasons, particularly in light of ethical and legal questions about the formation of museum collections. Ayer's purchases long predate the current practices employed by reputable museums, which generally avoid material without clear provenance. They also predate the international agreements in place relating to theft of cultural heritage. But Egypt has had laws that more or less strictly regulate purchase, and especially export, of antiquities since 1835, nearly 60 years before the Field Museum acquired its Egyptian collection. Were Ayer's purchases and exports legal under Egyptian law? This is unclear without specific documentation.

What is also noteworthy is that the Field Museum shares very little information on provenance (or lack of it) in its displays — in fact, nothing beyond the site or mere country of origin. For comparison, the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago — which also has Egyptian mummies and coffins on display, as well as ancient artifacts from West Asia — provides more detail: for unprovenanced material, this includes the year of acquisition, whether it was donated or purchased, and often where it was purchased. The visitor gets some idea of how artifacts make their way to museums, and is reminded that this isn't a passive process.

Perhaps natural history museums in general lack this information, but it is a remarkable absence. It is certainly an absence noticeable throughout the Field Museum. In the Africa galleries, the museum displays some of its large collection of Benin bronzes, removed by the British when they conquered what is now part of Nigeria in 1897. While this seizure is increasingly recognized as an act of looting — over the last two years a group of European museums have proposed arranging a series of loans (though not full repatriation) to Nigeria so that some of the bronzes are permanently on display — the Field Museum display makes little mention of how the bronzes left the Kingdom of Benin, and none of how they were acquired by the museum.

In this context, the Egyptian and Peruvian mummies' return to the Field Museum after a three-year tour is hardly a homecoming.

Another absence struck me, too. In the opening room of the Mummies exhibition there is a display that refers to the public spectacle of unwrapping mummies popular in Europe and the U.S. a century ago. The display mentions that these spectacles have gone out of favor with changes in both science and social norms. Note that this text is purely descriptive; pointedly there is no judgment as to the ethics of mummy unwrappings. This is the only reference to mummy display as spectacle in the exhibition.

To my mind, this is a missed opportunity to address the ethics of displaying mummies, or of displaying human remains in general. In recent years we have seen increasing sensitivity on the part of museums to the handling of human remains, notably in American museums with deceased Native Americans. But does this sensitivity extend to the Egyptian dead?

What some recent mummy exhibitions have done is emphasize respect for the dead, and emphasize treating mummies as human beings. We see this reflected in the Field Museum's exhibition, too, particularly in limitations on photography: signs indicate that photography of unwrapped human remains is prohibited. But is this really respect? And if so, is it enough? Western countries have a long, disturbing history of interactions with Egyptian mummies in particular — from grinding them into powder and ingesting them as a medicine during the Renaissance (sort of the collagen of the day), to using mummy powder as a pigment ("mummy brown" was apparently used in many European artworks up to the late 19th century), to an isolated case of turning decayed mummy flesh into candles and burning them. Compared to body parts kept as souvenirs by travelers, or mummies torn apart in the search for papyrus texts in their wrappings, this language of respect is certainly an improvement. But do mummy exhibitions continue this gruesome history on some level? We may have abandoned public mummy unwrappings, but is displaying mummies next to their CT scans simply a virtual unwrapping? I do not have any definitive answers to these questions, but I would have loved for the exhibition to engage more directly with them.

These questions deserve even greater attention given the importance of wrapping to ancient Egyptians. Historian Christina Riggs has recently strongly argued that we may have been getting the point of mummification wrong all along. If she is correct, preserving the body would have been less important than the process of wrapping itself, to sanctify the deceased — generally a high-status individual, since the bodies of ordinary Egyptians were not mummified — and treat them as divine. There is a gruesome irony in the obsession with unwrapping and humanizing mummies as a sign of respect if the entire point of the process, for ancient Egyptians, was deification.

These shortcomings are by no means restricted to the Field Museum exhibition —they are standard fare for contemporary mummy displays. Perhaps that is why all of this seems so normal. As art historian Elizabeth Marlowe has pointed out in Hyperallergic, museums are remarkably and subtly effective at making their collecting and display practices appear natural. Remember this as you visit the Field Museum and gaze upon the remains of the deceased, thousands of miles away from their homes in Peru and Egypt.

The exhibition Mummies runs through April 21 at the Field Museum (1400 S Lake Shore Drive, Chicago). The exhibition was curated by JP Brown (conservator), Robert D. Martin, William A. Parkinson, James L. Phillips, and Patrick Ryan Williams.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment