Tales of sunken cities

Doaa Bahey El-Deen, Tuesday 28 Sep 2021

The thrilling story of ancient cities submerged under the Mediterranean Sea should be told again and again to promote tourism and historical awareness in Egypt, writes Doaa Bahey El-Deen

A lighthouse that was once the tallest in the ancient world and an entire city underwater in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Alexandria: these are two aspects of recent discoveries that bear witness to an incredible cultural heritage that is more than 2,400 years old.

A young man, no older than 23, founded the most famous city on the Mediterranean Sea — Alexandria. In Egypt, the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great stopped on his way from Memphis to the Temple of Amun in Siwa at a fishing village on the Mediterranean coast called Ra-Qadt or Rakoda (Rhakotis) in 332 BCE. Across the water, the Pharos Island caught his eye and he immediately commissioned the architect Dinocrates to build a great city in his name.

He had come to Egypt looking for another conquest, and to celebrate he founded a cosmopolitan city at a location that is convenient by land and sea to become a crossroads of all corners of the world. The construction of the city lasted 80 years until it was completed during the reign of the Pharaoh Ptolemy II in the image of other ancient Greek cities with their luxurious palaces, temples, recreational areas, squares and courtyards decorated with fountains, statues, and other amenities.

Unfortunately, modern visitors will see few of these ancient monuments, though some still remain including Pompey's Pillar (the Memorial of Diocletian) and the Serapeum Temple, as well as the remains of the civic and recreational buildings in the central district of Kom Al-Dekka.

Coastal erosion due to rising sea levels is one factor that contributed to the disappearance of many of the ancient city's landmarks under water. Many researchers agree that the first sinking of the coastline was in the sixth century CE, when the city had many structures still standing.

The sinking of the city caused some structures in the eastern port to drown, however. They continued to sink between the seventh and 10th centuries CE, as water levels rose over the past two millennia.

In the last century, chief engineer of the Alexandria Ports and Lighthouses Authority Gaston Jondet began expanding the western port in 1910 and discovered the berths of an entire harbour submerged beneath the water. He studied the remains and dated them to even earlier than the founding of the city of Alexandria, an announcement that roused much local and international interest.

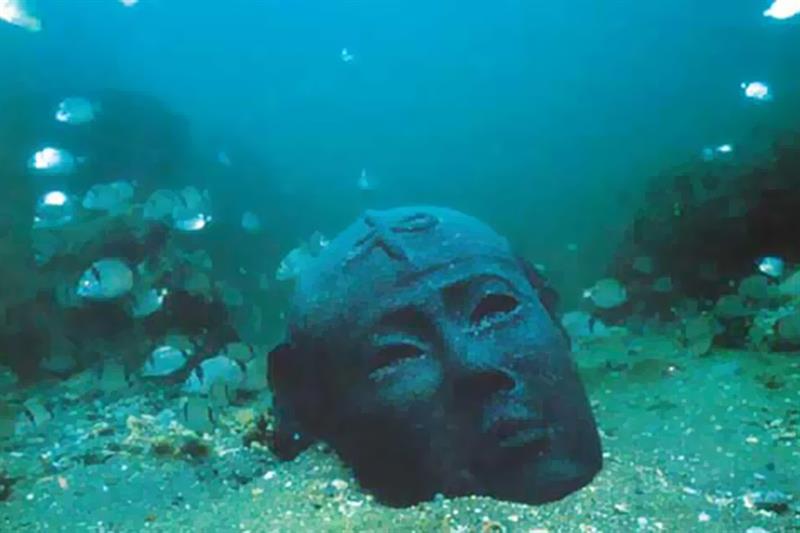

Later, a British RAF pilot was flying over Abu Qir near Alexandria when he noticed remains and structures in the water in 1932. Prince Omar Toussoun became involved and conducted an archaeological survey of the area that led to the discovery of a large number of columns and structural remains and statues, including a granite rendition of Alexander the Great's head.

Toussoun studied these pieces and concluded that they were the remains of the cities of Thonis-Heracleion and Minots (Minutis) and dated back to Pharaonic times. The two cities thrived as major harbours even before Alexandria was built.

In 1961, while diving in the Qaitbay area, Egyptian diver Kamel Abul-Sadat found a group of stone blocks, statues, columns and clay pots underwater. He plotted their coordinates and excavated a large statue that was eight metres tall and weighed 21 tons of Queen Arsinoe II, the wife of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, in the form of the goddess Isis, the Protector of the Seas.

Abul-Sadat made a map of the sunken antiquities he had found in the area and documented them.

The discovery ignited a revival of interest among ancient Alexandria researchers. British scientist Honor Frost accompanied Abul-Sadat on dives in the Qaitbay area, and together they were able to catalogue many pieces underwater, including a sphinx, granite blocks, and column bases.

REVIVING INTEREST: The discoveries caught the attention of the global community, making the trend grow beyond a hobby and become a scientific and research endeavour.

Laws and legislation were passed to protect cultural heritage below the water line, and new classes and programmes were created in European and US universities to study it. Egypt began underwater archaeological excavations at Alexandria in the 1980s that became more scientific in the 1990s.

A mission from the Centre d'Etudes Alexandrines under the leadership of French archaeologist Jean-Yves Empereur then began work, and one of its key achievements was to survey and excavate the remains of the Pharos Lighthouse that lay underwater near the Qaitbay Citadel. More than 3,000 artefacts were recovered, including statues (more than 25 sphinxes) and Greek and Egyptian columns.

There were also expeditions by the Italian CMAIA led by Paolo Gallo, the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA), the Institut Européen d'Archéologie Sous-Marine (IEASM) led by French explorer Franck Goddio, and Greek archaeologist of Alexandrian origin Harry E Tzalas, who created the Hellenic Institute of Ancient and Mediaeval Alexandrian Studies (HIAMAS) that carried out extensive archaeological surveys to uncover locations and artefacts.

In 1996, Egypt's Ministry of Antiquities established a new department due to this influx of excavations and growing interest called the Central Department of Underwater Antiquities (CDUA). This provided official oversight by Egypt of the work of foreign expeditions and partnered with them in archaeological research and survey work.

Our knowledge of the ancient eastern port has grown substantially in recent years. Due to the work of Goddio's team from IEASM, small ports were rediscovered underwater consisting of man-made piers and breakers and natural islands that enabled the overall shape and design of the ancient eastern harbour to be identified. Goddio published the results of these discoveries in a book entitled Alexandria: The Submerged Royal Quarters.

New underwater excavations at the lighthouse location revealed many other artefacts, including five segments of obelisks, 32 sphinxes, six columns with papyrus crowns dating back to the Dynastic era, the crown of a column, column bases, and 2,655 architectural blocks. There were also six large red granite statues of Ptolemaic kings and their wives in the image of Pharaohs, the largest of which was a statue of Ptolemy VIII that now stands outside the Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Alexandria.

The discoveries provided information about the historic, administrative, and economic circumstances of ancient Alexandria and its inhabitants in the Graeco-Roman era. Modern archaeological discoveries have had a great impact not only in telling the city's history, but also in explaining many old and new mysteries. Often archaeologists have referred to texts to explain what they have found, and often discoveries have explained the ambiguity of texts by ancient poets, geographers, historians and travellers.

A great technological leap forward in scientific research then impacted the study of sunken antiquities. Underwater archaeological research techniques have been revolutionised over the past two decades and characterised by the extensive use of remote-sensing and its role in discovering underwater sites.

The use of advanced underwater photography techniques to record and document sites has allowed the discovery and documentation of sites that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to reach using traditional methods.

While murky waters formerly hindered the exploration of the eastern harbour, the Hilti Foundation was able to locate the port east by using an advanced underwater search system using a Global Positioning System (GPS) to accurately pinpoint its location.

NEW DISCOVERIES: Discoveries at the ancient city of Thonis-Heracleion in the Gulf of Abu Qir in the spring of 2021 once again generated wide local and global interest.

CDUA Director Ihab Fahmi said the remains of a Greek funerary area dating back to the beginning of the fourth century BCE were excavated. Funerary vessels made of ceramic, a gold coin, and wicker fruit and vegetable baskets were found at the site, which indicated the presence of Greek merchants in this city that once controlled the entrance to Egypt at the mouth of the Canopic branch of the Nile.

The ancient Greeks settled in the city during the late Pharaonic era, when they constructed funerary temples near the main temple of the god Amun. This was later completely destroyed due to natural disasters.

Thonis-Heracleion was for many centuries the largest harbour on the Mediterranean before Alexandria was built. Several earthquakes followed by tidal waves later caused losses of the soil structure and the collapse of about 110 square km of the Nile Delta, until the rediscovery of a city that sank beneath the waves in the second century BCE.

The cities of Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus were rediscovered by an expedition from IEASM in cooperation with CDUA between 1999 and 2001.

Fahmi added that further excavations in the area, which operate under the supervision of the ministry of tourism and antiquities, have completed the excavation of a ship. The wreckage of the Ptolemaic era warship was found several years ago, and it appears to have sunk when large boulders from the Temple of Amun fell on it during a catastrophic event in the second century BCE.

Ironically, the falling boulders contributed to the preservation of valuable marine artefacts that settled on the bottom of a deep channel today filled with debris from the temple.

The wreck was discovered nearly five metres below solid mud, thanks to modern technologies such as sub-bottom profiler devices. Preliminary studies show that the body of the ship was built according to a combination of Egyptian and classic styles.

It was a ship with oars fitted with a large sail, as evidenced by the shape of the large mast, and it had a flat beam suitable for sailing on the River Nile and around the Delta. Typical features of shipbuilding in ancient Egypt alongside evidence of recycled timber show that the vessel was built in Egypt.

REPURPOSING DISCOVERIES: The US website Business Insider recently advised its readers to visit Egypt as one of the best tourist destinations worldwide after a tour of pop-up exhibitions of the underwater cities promoted tourism to Egypt and whetted the appetites of travellers to visit the country.

These included the "Osiris: Egypt's Sunken Mysteries" exhibition that toured Europe from Paris to London to Munich for 18 months in 2015-2016. There was also the "Sunken Cities: Egypt's Lost Worlds" exhibition at the British Museum in 2016 and again in the US in 2020, where it toured several states for six months.

The exhibition included more than 290 artefacts recovered from the watery graves of the cities in the eastern harbour of Alexandria. Visitors to the exhibition were very enthusiastic to visit Egypt and see its remarkable monuments.

While these exhibitions are key to promoting tourism and community awareness, displaying the antiquities and proper public exposure are also essential. Keeping the sunken treasures where they were found is a top priority for preserving the artefacts. Underwater museums are an ideal solution that can satisfy the passion of researchers and scholars, while preserving the antiquities in good condition.

The dream of creating an underwater museum to accommodate the sunken treasures in Alexandria remains alive, and it would be a remarkable tourist attraction. Despite all that has been discovered in the Mediterranean so far, the seafloor is still full of incredible treasures chronicling the history of these most important cities of the ancient Mediterranean coast and making the Mediterranean Sea the most important museum in the world.

Many important discoveries were made in the last century, including the Pharos harbour in Alexandria in 1910, the Sour (Tyre) harbour in Lebanon in 1931, Cherchell in Algeria in 1932, the port of Apollonia in Libya, the eastern harbour of Alexandria, the wrecks of ancient Greek ships, and the sites of Canopus and Thonis-Heracleion in Abu Qir.

But the number of untouched sites is also breathtaking, which makes the seeker of sunken antiquities embrace what Alexander the Great also believed: do not hesitate in conquering new worlds and achieving victory. Carpe diem.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 30 September, 2021 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment