Unlocking ancient Egyptian secrets

THE first thing to greet visitors to Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt is reminiscent of a highly engaging Jawi lesson. Large cubes are at the ready to be flipped for a quick comparison between the sounds of ancient Egypt, Greek, English and Arabic. Hieroglyphs are not just about pictures, they turned out to be an alphabet too.

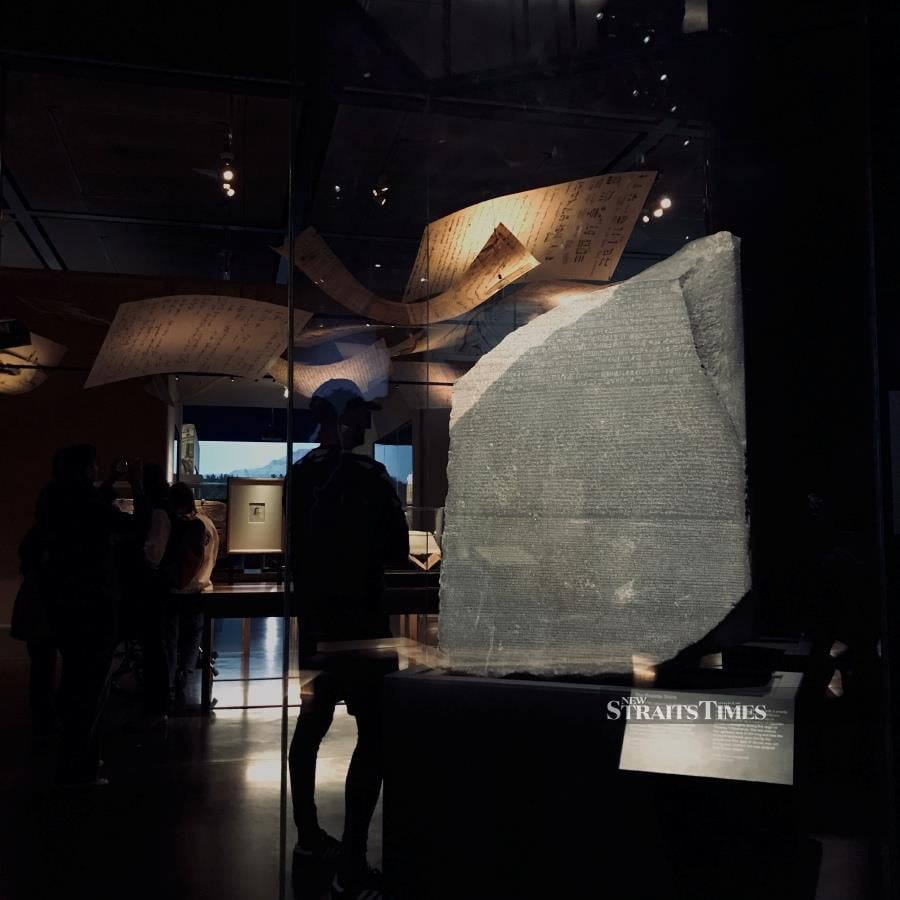

This year is the 200th anniversary of breaking the code of the Rosetta Stone. Most of the British Museum's latest exhibition is about this achievement. It might sound as dry as the Egyptian desert, but the curators have managed to generate some excitement with two scholars racing for the finish line.

If the thought of a Frenchman versus an Englishman battling it out for linguistic supremacy doesn't get the blood coursing through one's veins, there is an impressive array of background material to enliven their competitive spirit.

The stone's present location is the outcome of what some visitors might find more thrilling — endless military conflict between the two top colonisers of the 19th century and their relationship with the North Africans at the time.

Modern Egypt has now stepped into the controversy. With cultural-restitution wars raging all around, the Egyptian archaeologist-in-chief, Zahi Hawass, recently relaunched a campaign to bring the stone home.

As Britain's flagship cultural attraction is the Rosetta Stone, it seems strange not to see this prize in its usual place of public display. The crowds are still there, gawping at empty space, while the stone is now the centrepieces of a (paid-for) exhibition.

LINK BETWEEN LANGUAGES

The display has improved. Unlike the British Museum's permanent gallery of ancient-Egyptian wares, the exhibition space is filled with drama, superior lighting and even the sound of Coptic chanting.

This community was the link between the languages of hieroglyphs and a more comprehensible alphabet, they have not been forgotten. Nor were they overlooked in centuries past. Rome was well furnished with pharaonic souvenirs on a grand scale long before Mussolini went to Ethiopia to grab some monumental art.

One of the exhibits is an Egyptian obelisk. It's only a fragment, and the imagery is a bit fuzzy, but it's given some real context by the enlarged print next to it. On this it is recorded how Pope Pius VI had the 2,600-year-old red-granite monument moved in 1748 to the Piazza di Montecitorio from where Emperor Augustus had placed it after a long journey from Heliopolis. The obelisk is in the same square today — minus the piece that is being lent by the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

More than a century later, a member of the infamous Borgia family took an interest in the Copts, whose culture had been overtaken by Arab Muslims around the year 640. His curiosity was aroused, as with later linguists, by the continuity of the Coptic language from what was spoken in more-ancient Egypt. It is a succession that is central to the exhibition.

Exploration of those links between antiquity and the growth of Coptic culture is, however, a lower priority than the determination of Jean-Francois Champollion and Thomas Young to break the code and release all that information stored in the form of hieroglyphs.

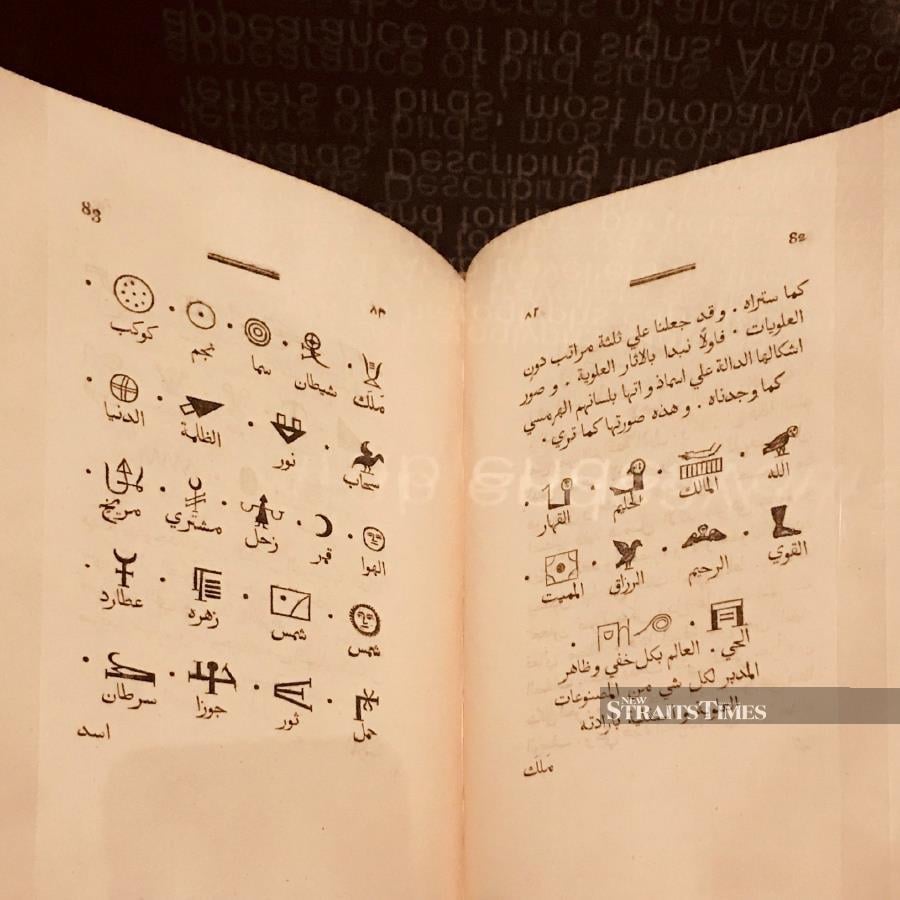

Earlier scholarship is on display too, mostly the work of Arab historians and linguists, although their descendants in the 19th century accepted that the Western interlopers had made a huge amount of progress, not just with the ancient languages, but also with Arabic.

PLENTY OF MYSTERY

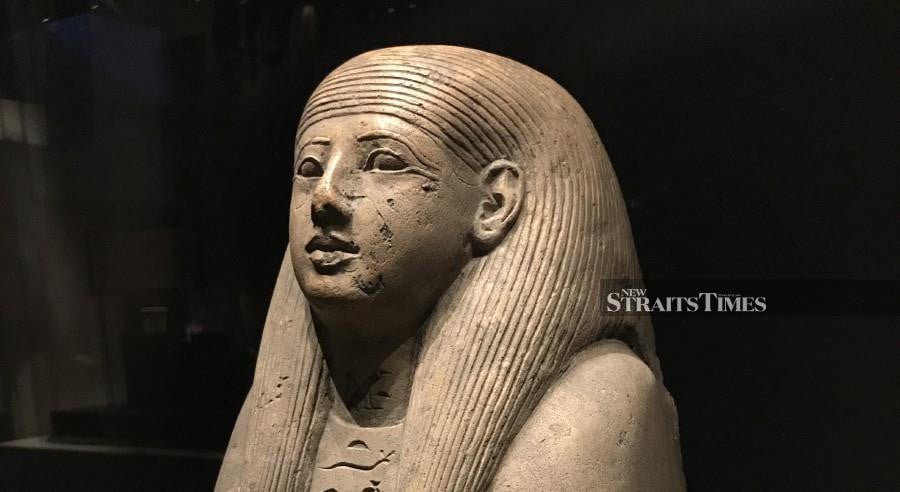

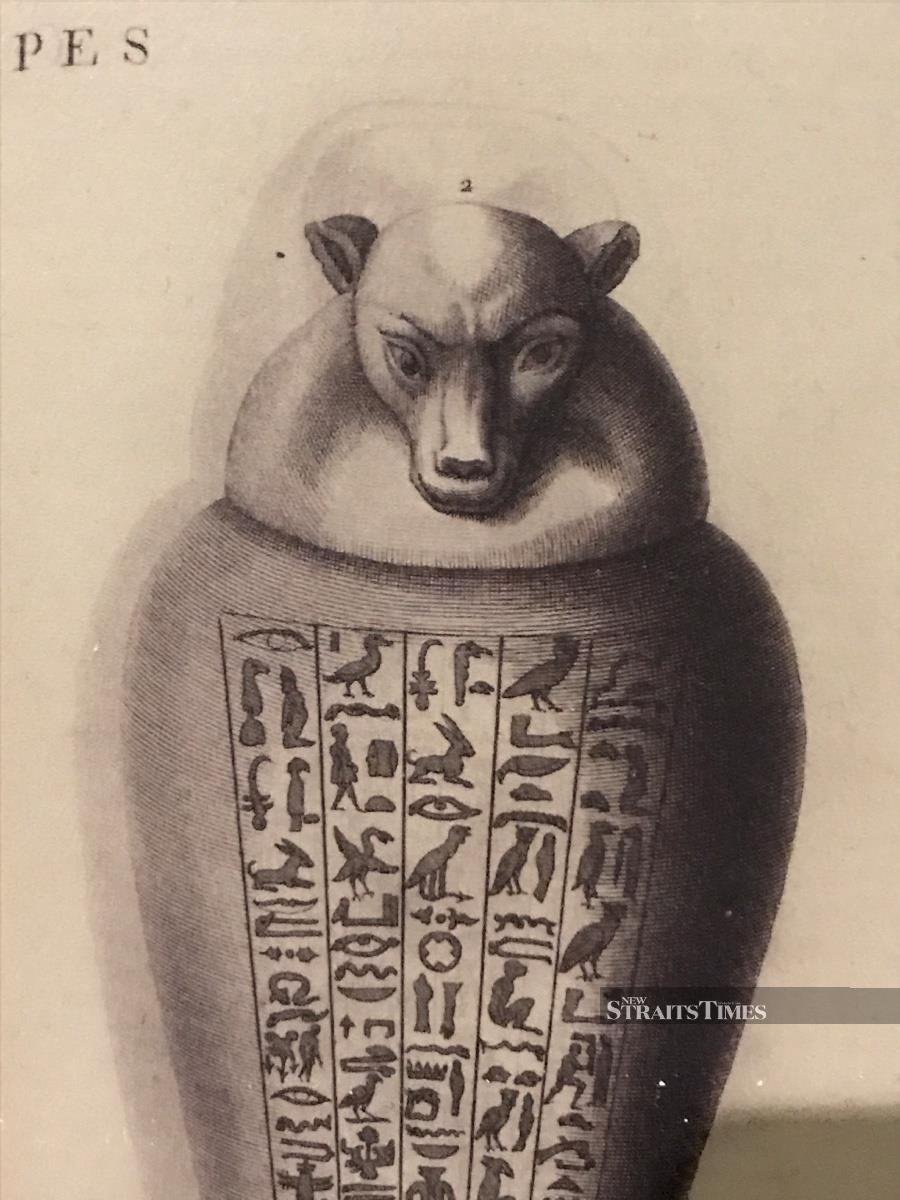

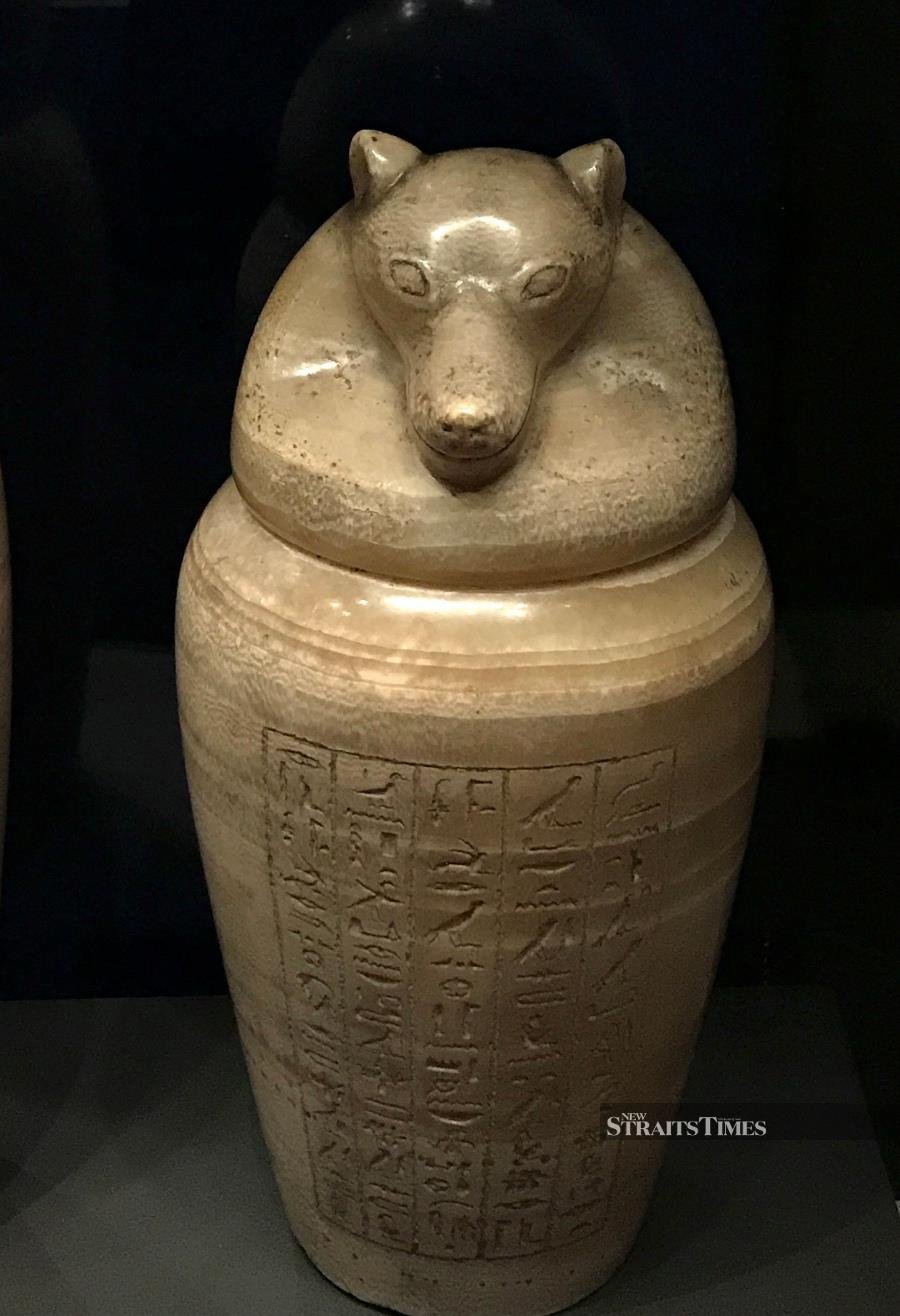

Along the way, we get to see the old favourites of Egyptology. As hieroglyphs appear on almost everything, there is no shortage of sarcophagi and canopic jars. These are accompanied by a profusion of "shabti" mini-mummy figures that used to have a place in learned homes around the world. The famous Book of the Dead also puts in an appearance. It turns out to be neither a book nor even a fixed text, but in its different manifestations, it is at least about the dead.

Throughout the exhibition, there's an emphasis on prayers for the dead. Much of it will make the ancient Egyptians seem more "normal" about death than some of the mythology about them suggests.

Visitors looking for cat mummies will be disappointed. This is too serious a show for that, although you can still see a good selection upstairs for no entry charge. There are also some statues, probably dedicated to the cat goddess Bastet. The accompanying label reveals that cat in ancient Egyptian is "mioew".

With the Rosetta Stone decrypted, there was so much valuable information suddenly available. Two hundred years on, there's a still a lot of mystery and some assumptions that don't seem entirely credible.

One such item in the exhibition is the caption accompanying a tiny mineral figure of Isis with Horus on her lap stating that the imagery was "later adapted by Christians for the Virgin and child".

In this case, no quantity of deciphered hieroglyphs is going to get to the truth of the claim. Around the world, there are countless mother-and-child images created by societies that never knew anything about the pantheon of ancient Egypt, nor how to read hieroglyphs.

Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt at the British Museum ends on Feb 19, 2023.

Follow Lucien de Guise at Instagram @crossxcultural.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment