https://hyperallergic.com/511565/striking-power-iconoclasm-in-ancient-egypt/

Art

What Centuries of Damage to Ancient Egyptian Artifacts Might Mean

The power relations presented in an exhibition at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation are selective. We get a discussion of ancient power — but what about the modern power to acquire these objects regardless of legal or ethical concerns?

St. LOUIS, Mo — "Brethren, I deem it more shameful for Hercules to have his beard shaved than to have his head taken off." So runs one of St. Augustine's sermons about breaking pagan statues, as quoted in material produced by the Pulitzer Arts Foundation for their current exhibition Striking Power: Iconoclasm in Ancient Egypt.

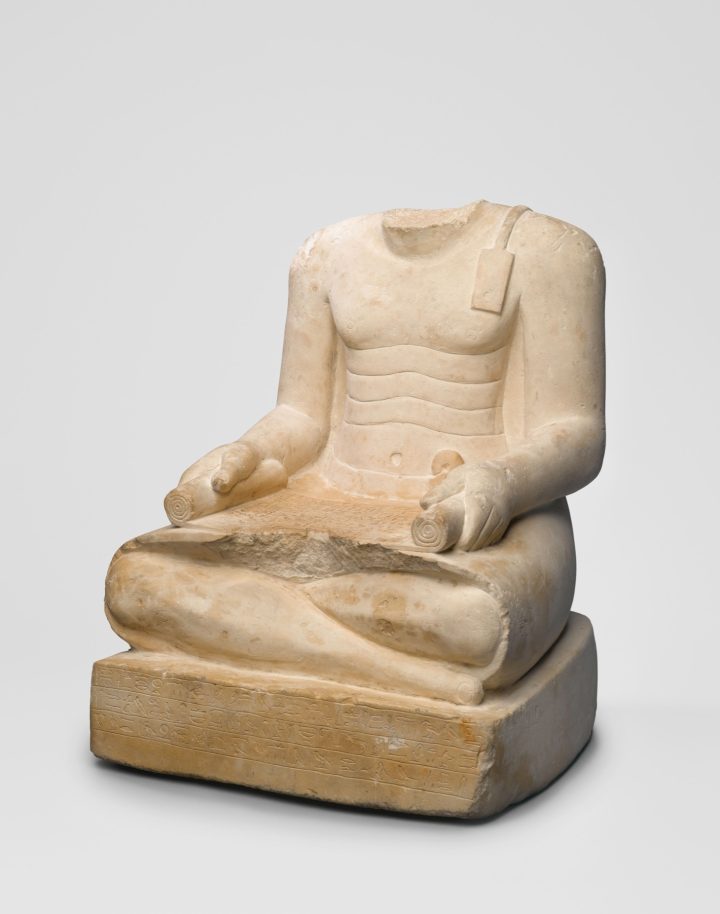

Iconoclasm is the purposeful destruction of images for religious or political reasons. The Pulitzer exhibition, organized in collaboration with the Brooklyn Museum, gathers together 40 ancient Egyptian objects, most of which appear to have been purposely damaged at different times in the ancient past.

Trained as an archaeologist, I am always a little disoriented when seeing ancient artifacts treated first and foremost as art objects. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art recently, I was startled to hear a security guard at the Temple of Dendur call out to visitors to keep a foot away from "the art." At the Pulitzer, seeing Egyptian artifacts as works of art is encouraged even more. The galleries are sparsely filled — 40 is a small number of objects for a half-dozen galleries — and have no labels or other text. (Museum staff told me when I entered the exhibition that they thought the labels would detract from the art.) The result is that, against the blank white walls of the galleries, the Egyptian statues and reliefs are treated much like the contemporary art that usually graces the Pulitzer.

The Pulitzer doesn't ignore the original ancient contexts of their art, though. Visitors are provided with a museum guide booklet that includes typical museum label information for each object, as well as additional information on iconoclasm, and on Egypt in the periods in question.

The 40 objects on display include material made throughout Egyptian antiquity (spanning some 2,500 years), but four distinct periods are emphasized: the reign of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut in the 15th century BCE; that of the pharaoh Akhenaten in the 14th century BCE; the fourth to sixth centuries CE; and the seventh century CE onward.

Why are these periods singled out? There are special circumstances in these periods that led to iconoclastic acts, and co-curator Edward Bleiberg of the Brooklyn Museum provides a model to identify when and under what conditions a specific statue was damaged.

The memory of the pharaohs Hatshepsut and Akhenaten were both targeted for erasure: Hatshepsut as stepmother of the succeeding pharaoh, in what may have been an attempt to legitimate the change in the line of succession; Akhenaten for his rejection of traditional gods — and their powerful priesthoods — in favor of worshipping the Aten, the sun disk, alone. (This means that their names and images in particular, as opposed to others alongside them, were specifically attacked.) Once Christians became ascendant in the Roman empire, they began to destroy "pagan" monuments. And with the Muslim conquest of Egypt in the seventh century and the rise of Islam as a major religion in the country, statues of the pharaonic past were no longer seen as having power (and their inscriptions were no longer understood), and were often reused as building blocks for new constructions.

This categorization of iconoclasm makes much sense, and it is very helpful for thinking through the different reasons and the different ways that statues were damaged in the past. But the categories are perhaps too rigid.

How do we know that damage is intentional? In some cases the chisel marks leave no doubt. But in others it is less clear, and unfortunately neither the museum guide nor the accompanying catalogue go into great detail. Meanwhile, in a few cases it is suggested that statues were damaged by ancient tomb robbers. Could any damage be caused by modern looting or other activities?

The Christian destruction of Greek and Roman monuments came to the fore recently with the 2018 publication of journalist Catherine Nixey's book The Darkening Age. Nixey rehashed the arguments of 18th-century historian Edward Gibbon, blaming Christians for the widespread destruction of classical antiquity — its monuments as well as its texts — and the fall of the Roman Empire. The reality, as scholars showed in reviews of Nixey's book, is more complex. Above all, the reports of fourth- to sixth-century destruction of "pagan" monuments and statues, while having a basis in reality, are likely exaggerated. When looking at the exhibition's easy (perhaps too easy) classification of Christian damage to sculptures, it's worth keeping that in mind.

Striking Power's treatment of Islamic-period damage to monuments also needs to be dealt with carefully. Historically, damage to ancient sculptures in the Islamic period was often seen as the result of Muslim "fanaticism," even if this was exaggerated or imagined by European and American observers in many cases. Thankfully that claim is avoided here. Instead, the exhibition attributes damage in these periods to simple reuse: Muslims no longer understood what these monumental statues meant, so they reshaped them into building blocks for new construction. There is some truth to this, but again there is much more to the story. Like supposed Muslim fanaticism, reuse of material was long seen as a sign of the backwardness of Egyptians. "It is a melancholy thing," wrote the 18th-century English clergyman and traveler Richard Pococke, "to see how the barbarous people of these countries continually destroy such magnificent buildings, in order to make use of the stone." This attitude is far from unique. It has been used for centuries to justify European and American looting of objects from Egypt and the entire region — they belong to us because we care more about them than they do.

Again, the truth is more complex. There was a variety of attitudes among Egyptian Muslims toward the past, including reuse as a positive value, to incorporate the power of the past into new buildings. And, of course, the reuse of stone is a common phenomenon throughout history and throughout the region. (In my own experience as an excavator, the one time I came across an Egyptian-style sculpture was as a reused stone in a Philistine wall, at the site of Ashkelon in modern Israel.) Are all cases of reuse in Striking Power necessarily from the Islamic periods? Again, the exhibition seems to oversimplify the situation here.

At an exhibition centered on destruction of statues, at this moment in history, the visitor can't help but wonder if it is meant to evoke contemporary cases of iconoclasm. On this the museum guide is silent. But in the catalogue for the exhibition, the director's foreword suggests a parallel with "the current moment, as global communities grapple with the future implications of decisions made about the historical artworks and monuments that still surround us today." Is this meant to refer to ISIS, Confederate statues, or something else? In her essay in the catalogue, co-curator Stephanie Weissberg of the Pulitzer makes clear that the curators had both ISIS and Confederate monuments in mind, along with a number of other modern examples.

* * *

As always, one of the first questions to ask when visiting an exhibition of antiquities is "Where did these come from?" Provenance is crucial, so it's unfortunate that there's little discussion of it in the exhibition. Object descriptions in the museum guide sometimes give us a site (with a question mark, or "probably from", or "said to be from"); sometimes only a region of Egypt ("Upper Egypt"); or sometimes just "from Egypt." This lack of specifics points to the fact that most of the objects are ultimately unprovenanced, since they were originally purchased from antiquities dealers. There are some exceptions: one item on loan, not from the Brooklyn Museum but the MFA in Boston, excavated at Giza in 1911; and two stele fragments from the site of Tell el-Amarna, which were gifted by the Egypt Exploration Society (which excavated the site) in 1936.

Beyond that, the entries merely list the museum accession number, the year of accession, and the donor or fund used to make the purchase — mostly Charles Edwin Wilbour and his family. Wilbour is a fascinating figure: a late 19th-century amateur Egyptologist, highly respected by the professionals of his time, who used his great wealth (he was said to have become rich through Boss Tweed's Tammany Hall political machine) to amass a large collection of artifacts purchased in Egypt.

So, while we learn about the ancient contexts of these artifacts, their modern histories are ignored. On one level, we lose fascinating object biography. Take the five statues on display that are headless. When they were first brought to the United States, two of them did have heads! In fact, the Brooklyn Museum determined in 1949 — several decades after the acquisition of the statues in question (a block statue of Minmose and a statue of the scribe Djehuti) — that those two heads were added in modern times, one originally from a different ancient statue, the other a modern creation. The two statues' original heads, it turned out, had been broken off in antiquity. (The Met's recent exhibition World Between Empires displayed a similar example from Palmyra, now owned by the Louvre, again without highlighting the history of its one-time head.)

On another level, more serious issues get downplayed. While the catalogue includes no further discussion of provenance, the museum guide includes a paragraph in the Frequently Asked Questions section on "When were these objects acquired by museums?" And here we meet something peculiar. The museum guide indicates that 34 of the 40 objects were acquired by the Brooklyn Museum before 1970, and so are "designated as legal acquisitions" under the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property — except this does not correctly state what the 1970 UNESCO Convention does. That international agreement calls on member states to regulate import and export of antiquities, but does so through reference to national antiquities laws, and calls on states parties to follow the existing national laws of other state parties. Over time, many institutions and organizations have looked to the 1970 UNESCO Convention to set a cutoff date, only acquiring or studying objects that are known to have been out of their source countries after that date — unless they have proper export documentation. But this is ultimately a matter of codes of conduct and best practices, not of law. (This misunderstanding of the 1970 UNESCO Convention appears to be widespread.)

The key point is that acquisition of objects traced back before 1970 is not necessarily legal. In this case, it is the national antiquities laws of Egypt that would determine the legality of the acquisitions. What do those laws say? The current law, banning sale and export of all antiquities, was passed only in 1983. But the sale and export of antiquities has been regulated under previous Egyptian laws since 1835. There was a legal antiquities trade, including sales conducted in a room of the Egyptian Museum itself (typically of mummies and small finds, not large statues, and typically to museums). But in theory this trade was highly restricted. Yet Europeans and Americans still highly desired ancient Egyptian artifacts, leading to widespread smuggling out of the country in the 19th and early 20th centuries, whether by cutting up papyri and hiding them among photographs, or using elaborate ruses involving crates of oranges, or simply bribing customs officials. And so the status of the artifacts on display in Striking Power is much less clear than any reader of the museum guide would think.

The power relations presented to us in the exhibition are selective. We get a discussion of ancient power — but what about the modern power to acquire these objects regardless of legal or ethical concerns? If anything, the focus on these artifacts as art objects obscures questions of acquisition and ethics. At the same time, it is worth noting that the Pulitzer hosted a conversation on provenance and museum ethics on June 27. We can only hope that the museum will build on this public work and shine a stronger light on these issues, issues unfortunately downplayed in the current exhibition.

Striking Power: Iconoclasm in Ancient Egypt runs through August 11 at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation (3716 Washington Boulevard, St. Louis, Missouri). The exhibition was curated by Edward Bleiberg, a senior curator of Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern Art at the Brooklyn Museum, and Stephanie Weissberg, an associate curator at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation).

-- Sent from my Samsung Galaxy Tab S4 running Ubuntu Linux.

No comments:

Post a Comment