Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

November 2023

Vol. 11, No. 11

-- Sent from my Linux system.

Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

Sex and gender have become central topics of discussion and scholarship in a wide variety of fields, ever since second-wave feminism emphasized the distinction between these two aspects of biology and culture. Scholars of antiquity are now trying to understand how the denizens of the ancient world, such as in Mesopotamia and Egypt, understood these concepts in their own cultures without retrojecting modern interpretations onto the past. Here we consider how people in the ancient world thought about sex and gender in terms of their language and artifacts.

"Sex" refers to which one of two roles an organism plays in those forms of reproduction that combine the genes of two organisms in the creation of the next generation. Those organisms that produce the smaller, penetrating gametes are known as males; those organisms that produce the larger, nourishing gametes are known as females. This goes for humans, most vertebrates, and several species of plants.

"Gender" is comprised of the beliefs held about individuals based on their sex. All world cultures have some notions of aspects of personality or intellect that are supposedly sex-based: Males are more violent; females are more nurturing. Males are better at math, females have better verbal skills, et cetera. These beliefs are profoundly significant, for they — consciously or not — influence how individuals in a society learn to act and self-identify, and how other members of that society expect each other to behave. The result is a constantly self-reinforcing process whereby males learn to act in a "masculine" fashion and females "feminine," strengthening the belief that males are innately masculine and females feminine, for whatever counts as "masculine" or "feminine" in that particular community. These aspects of behavior are taken as innate and justify relations between the sexes and their roles and positions within the overarching community.

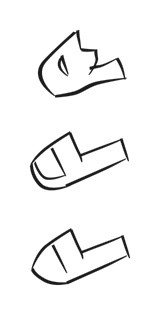

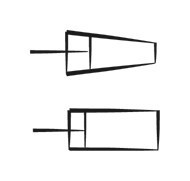

The societies of the ancient Near East had a binary sex paradigm—female and male— and had notions of how these two sexes were supposed to be and behave, to wit: gender. The binary nature of biological sex is most easily manifest in the ideograms they used when discussing human beings: Basically, they used pictures of their genitalia. In early Mesopotamia, for example, the idea of a generic human being was expressed by the Sumerian sign SAG:

To render a human male the UŠ sign was used (also transcribed NITA), an ejaculating penis:

To make a human female the SAL sign was used (also transcribed MUNUS), a vulva:.

So "woman" equals "human with vulva" and "man" equals "human with penis". There isn't much by way of ambiguity.

Likewise in Egypt. More commonly, males and females were distinguished using the signs A1 and B1, which show the entire body: ![]() for a male and

for a male and ![]() for a female. But, not to be outdone by their northeastern neighbors, the Egyptians could also render sex with graphic genitalia:

for a female. But, not to be outdone by their northeastern neighbors, the Egyptians could also render sex with graphic genitalia: ![]() and

and ![]() (you can guess which is which on your own).

(you can guess which is which on your own).

In addition to this notion of binary sex were notions of gender, i.e. the quality of being feminine (the way a female is supposed to be) or masculine (the way a male is supposed to be). Again, this comes across in the vocabulary. In Mesopotamia, both Sumerian and Akkadian have words for the "state of being a woman" or "state of being a man." In Sumerian these are NAM.MUNUS and NAM.NITAH; in Akkadian they are sinnišūtu(m) and zikrūtu(m). Sumerian NAM refers to a state of being or fate; the Akkadian suffix –ūtu refers to a state of being or –ness quality. Thus, femaleness or the state of being male.

Gendering also manifests in art. For example, in ancient Egypt, there were stylistic conventions used to distinguish between male and female that did not necessarily have anything to do with reality. Males are consistently bigger (up to 60% bigger!) than the women they are shown with, have darker skin, are shown in more active poses, and are less eroticized than females (that is: female genitalia are often visible through clothing, male genitalia most assuredly are not). For example:

So, how did the ancients engender their sexes? While much depends on time and place, some basics can be established. In general, femininity consisted of the qualities of eroticism and beauty, nurturing, intermediary, and domesticity. Masculinity consisted of fertility, violence, and professionalism.

Concerning the first categories: Females, both human and divine, were understood to enjoy sex themselves and to arouse males with their beauty in the process (we have no data on lesbianism, unfortunately). The males then generated new life which they then gave to the females to incubate and nourish both inside and outside of the body. So in reproduction, males were fertile (create new life), while females both stoked the preceding desire (beauty and eroticism) and tended to the offspring (nurturing). Thus, from the Sumerian Disputation between Wood and Reed:

The great earth (KI) made herself glorious, her body flourished with greenery.

Wide earth put on silver and lapis lazuli ornaments,

Adorned herself with diorite, chalcedony, cornelian, and diamonds.

Sky (AN) covered the pasture with (irresistible) sex appeal, presented himself in majesty.

The pure young woman showed herself to the pure Sky,

The vast Sky copulated with the wide Earth,

The seed of the heroes Wood and Reed he ejaculated into her womb.

The Earth, the good cow, received the good seed of Sky into her womb.

The Earth, for the happy birth of plants of life, presented herself.

(translation from Leick 1994, 18)

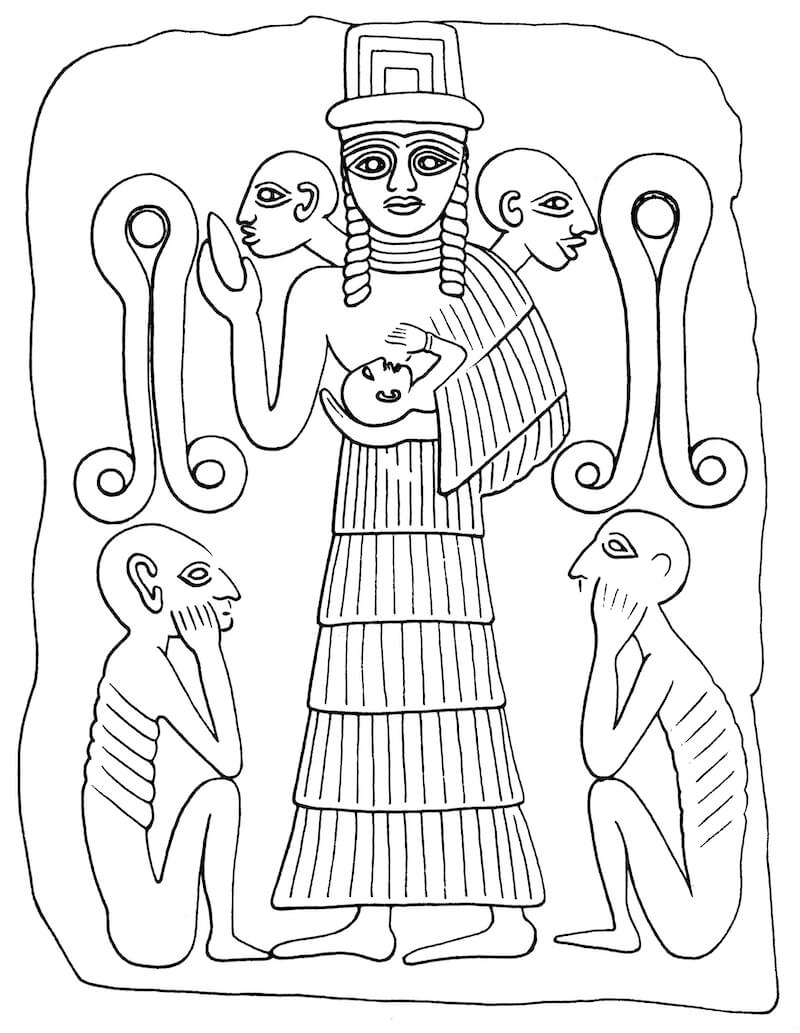

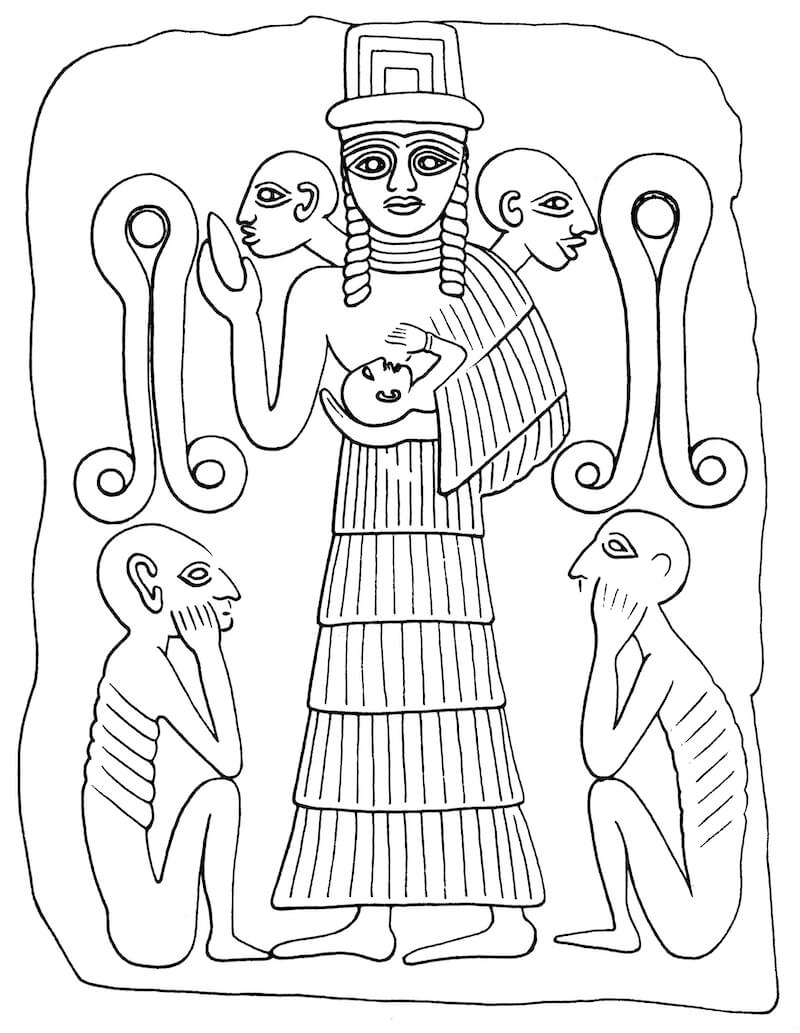

The feminine nourishing of offspring comes across in the very consistently female images known as kourotrophoi ("child-nurturers"):

The masculinization of violence appears in the ongoing association of males with weapons. An Ur III-period birth incantation claims:

If it is a male, let him take a weapon, an axe, the force of his manliness.

If it is a female, let the spindle and the pin be in her hand.

(Translation from Stol 2000: 61)

The battlefield itself is known in Sumerian as the field of manhood (KI NAM-NITAḪ-KA). While it was inevitably better for Egyptian men to show self-control, the king himself might proclaim:

I have curbed lions, I have carried off crocodiles, I have crushed the people of Wawat, I have carried off the Medjay, I have made the Asiatics slink like dogs!" (King Ammenemes to his son Sesostris I; translation from Faulkner in Simpson 1973, 196)

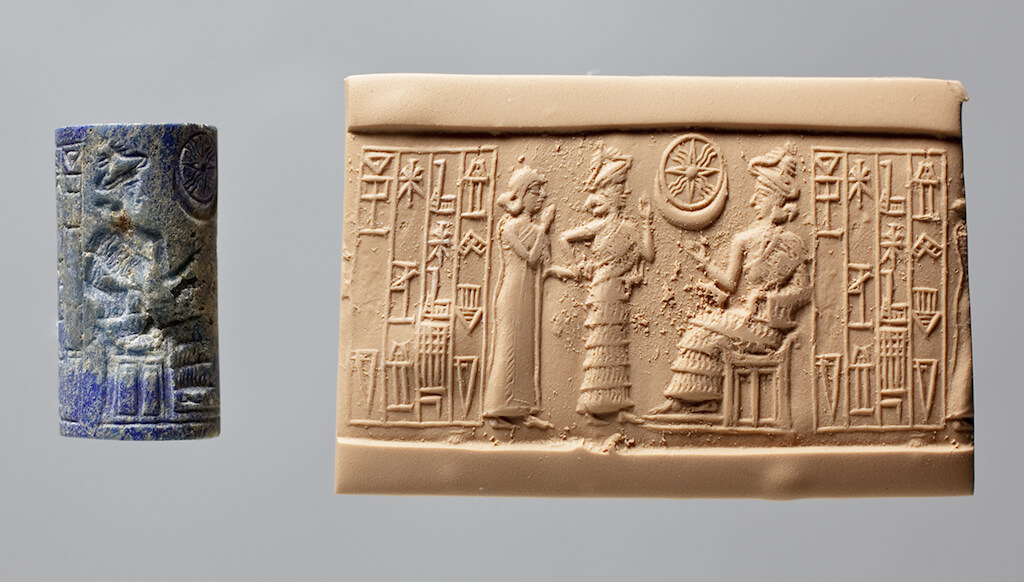

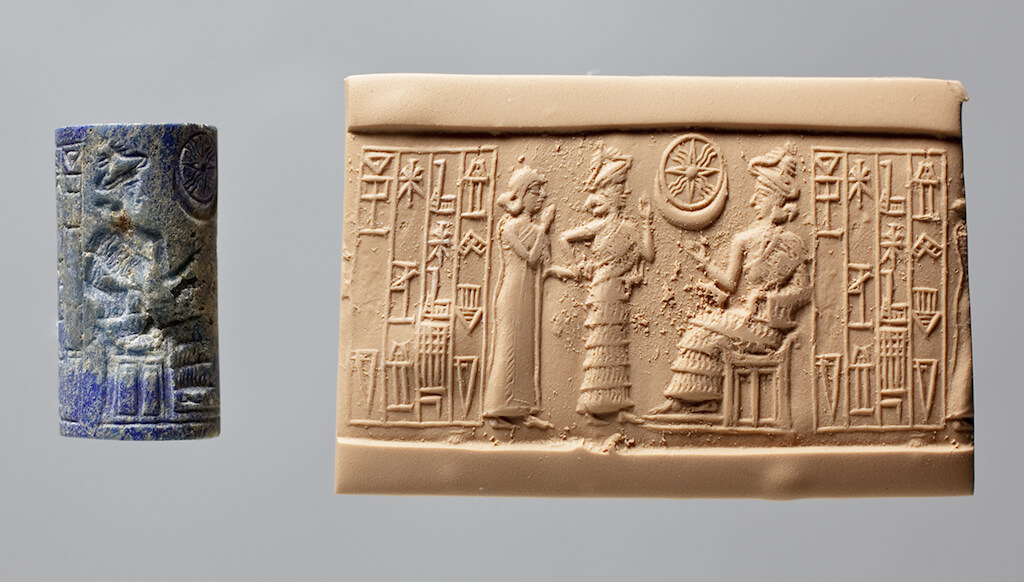

By contrast, it was seen as the role of females to function as intermediaries. This is especially so with goddesses who connected mortals to higher divinities, as with the Mesopotamian Lamma goddess:

Or the Egyptian goddesses Nut and Neith, who presented the dead king to the deities:

"I call your mother Nut to you,

and Tefnut on your left side,

that they may throw their arms around you

and recognize their son in you.

I bring you Horus, that he may worship you,

I set you upright and let him speak to you.

He brings you your enemies as prisoners

and annihilates them beneath you, forever." (Neith speaking in the Coffin Text of King Merenptah; translation from Assmann 2005, 169)

Regarding domesticity and professionalism, inevitably, regardless of what kinds of professions women actually held (and there were many), men were always more associated with having jobs than females, who were more associated with their families. This is pithily summarized in an Egyptian aphorism from the Instructions of Any:

A woman is asked about her husband,

A man is asked about his rank.

Gender is about ideas, not reality.

Gender bending took place in the ancient Near East, usually making females masculine. This provided women with the prerogatives of men, while still understanding that the females were, in fact, female. Perhaps the most famous example of this was Pharaoh Hatshepsut, who adopted masculine attributes in her iconography such as the nemes headdress and lion kilt, while still maintaining her feminine titulary:

Horus Name: wsrt-kӡw = "Powerful (f.) of kas"

Nbty Name: wӡḏt-rnpwt = "Flourishing (f.) of Years"

Golden Horus Name: nṯrt-ḫʻw = "Divine (f.) of Appearance"

Prenomen: mӡʻt-kӡ-rʻ = "True one (f.)/Ma'at of the ka of Ra"

Nomen: ḥӡt-špswt = "Foremost (f.) of Noblewomen"

In northern, first-millennium Mesopotamia daughters could be turned into sons (and mothers into fathers) to give brotherless girls rights to the family fortune and ancestor cult. Thus from the city of Emar we read in the last will and testament of Ḫaya, son of Ipqi-Dagan (Emar 6 31):

[Bef]ore Šaḫurunuwa, son of Šarri-Kušuḫ, king of Ka[rkemi]š, Haya, son of Ipqi-Dagan, has created this contract regarding his household. He has established his daughter Dada, the ḫarīmtu, to fatherhood and motherhood (ana abbūti u ummūti) of the household.

I have adopted as sons my two daughters Dagan-niwari and Abi-qiri (DUMU.MUNUS–ia gal ana DUMU.NITA–ia etepuššunu). I have given Dagan-niwari as wife to Alal-abu. If [Dagan-niwari does not bear offspring], Alal-abu shall take another wife.

(Translation after Justel 2014, 131)

The adoption as sons did not preclude the daughters from marrying and being expected to give birth: they were still understood to be female. But females with benefits.

Gender bending in the reverse direction—feminizing males—was inevitably intended as an insult, usually on the über-masculine field of battle. When Pharaoh Merenptah sought to humiliate his traditional enemies, the "Nine Bows", he inscribed:

pḏ.wt psḏ.t hr- ḫӡ.t=f mj ḫnr.yt

Nine Bows are before him [the king] like women of the harem. (Kom el-Ahmar Stele; Matić 2021, 116)

Likewise, the curse summoned by the Assyrians upon those who would break their oaths of allegiance:

If Mati'-ilu sins against this treaty with Aššur-nerari, king of Assyria, may Mati'-ilu become a ḫarīmtu [woman without father or husband], his soldiers women, …may Ištar, the goddess of men, the lady of women, take away their bows, bring them to shame…

(State Archives of Assyria 02, translation adapted from Oracc)

Sex was not fluid in the ancient Near East. Neither, for the most part, was gender. But how the one got applied to the other was totally up for grabs.

Stephanie Budin is an Independent Scholar and Editor of the journal Near Eastern Archaeology. Her book, Gender in the Ancient Near East, was recently published by Routledge.

Further Reading / Source Translations

Assman, J. 2005. Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt. Translated from the German by David Lorton. Cornell University Press.

Budin, S. L. 2023. Gender in the Ancient Near East. Routledge.

Graves-Brown, C. (ed.). 2008. Sex and Gender in Ancient Egypt: 'Don your wig for a joyful hour'. The Classical Press of Wales.

Justel, J. J. 2014. Mujeres y derecho en el Próximo Oriente Antiguo: La presencia de mujeres en los textos jurídocos cuneiformes del segundo y primer milenios a.C. Libros Pórtico.

Laboury, D. 2014. "How and Why did Hatshepsut Invent the Image of her Royal Power?" In J.M. Galán, B.M Bryan, and P.F. Dorman (eds.) Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut. Oriental Institute of Chicago, 49–91.

Leick, G. 1994. Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature. Routledge.

Matić, U. 2021. Violence and Gender in Ancient Egypt. Routledge.

Peled, I. 2016. Masculinities and Third Gender: The Origins and Nature of an Institutionalized Gender Otherness in the Ancient Near East. Ugarit-Verlag.

Robins, G. 1996. "Dress, Undress, and the Representation of Fertility and Potency in New Kingdom Egyptian Art." In N.B. Kampen (ed.) Sexuality in Ancient Art. Cambridge University Press, 27–40.

Roth, A. M. 2005. "Gender Roles in Ancient Egypt". In Daniel C. Snell (ed.) A Companion to Ancient Near East. Blackwell Publishing, 211–218.

Simpson, W.K 1973. The Literature of Ancient Egypt. Yale University Press.

Stol, M. 2000. Birth in Babylonia and the Bible: Its Mediterranean Setting. Styx Publications.

Svärd, S. and A. G. Ventura, eds. 2018. Studying Gender in the Ancient Near East. Eisenbrauns.

Winter, U. 1983. Frau und Göttin: Exegetische und ikonographische Studien zum weiblichen Gottesbild im Alten Israel und in dessen Umwelt. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 53. https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/138333/

Zsolnay, I. 2017. Being a Man: Negotiating Ancient Constructs of Masculinity. Routledge.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment