A modern ancient Egyptian temple atop the Met Museum reflects on race, place and space

A new ancient temple rises atop the Metropolitan Museum like a blazing hallucination. From below, it looks as though the 2,000-year-old Temple of Dendur had levitated up from its ground-floor gallery to sunbathe on the roof or get a better look at Cleopatra's Needle, the 3,500-year-old obelisk planted in Central Park. But Lauren Halsey's rooftop commission is a fresh shrine, blindingly white and elaborately adorned with late-model hieroglyphs that speak a contemporary vernacular. It's a time ship, too, shuttling between the past and the future and making a summer-long port of call at the Met.

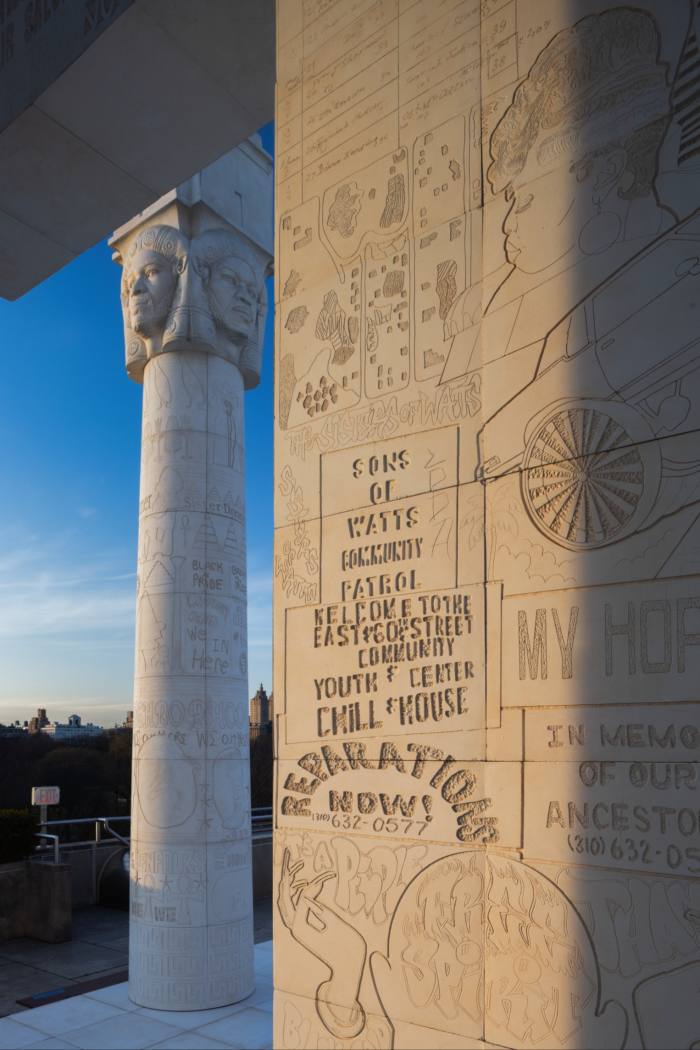

The extravaganza looks at home here, blending easily with the sawtooth skyline and tousled vegetation of Central Park. Its pair of sphinxes might be distant cousins of Patience and Fortitude, the lions that guard the New York Public Library, 40 blocks down along Fifth Avenue. The thick columns, weighty lintels and deceptively minimalist enclosure might have been inspired by any number of retro residences on the East Side.

But "the eastside of south central los angeles hieroglyph prototype architecture (I)" comes from, and will return to, South Los Angeles, evolving from a museum piece into a promoter of urban life in an area badly in need of all the qualities that Halsey's opus represents: ceremony, stability and celebration. This is a work that deals only tangentially with Egypt or New York; it's about black LA, a community where Halsey's roots reach deep and that she has regularly left, only to return again and again.

Even as a girl riding to grade school in her father's car or, later, taking the bus to college at CalArts, she noticed how the landscape changed abruptly when she crossed an invisible border. Beyond it, she observed patios, pediments and carefully tended shrubs lining gracious boulevards. Closer to home, she saw minimarts bristling with warnings and surveillance, laid out on hard, unshaded streets. And yet this was and is her home, and she uses art to express her complicated feelings towards it, a mixture of love, anger and aspiration.

Most of Halsey's work shivers with colour. She loads collages, installations, paintings and digital prints with the shiny polychrome castoffs of mass-production: trinkets, ads, toy cars, magazine clippings, posters, leaflets and any other bright scrap that catches her voracious eye. In the 1960s, the architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown photographed Las Vegas's surfeit of signage as a way to enshrine the American streetscape. Halsey, who studied architecture for a time, taps a similar mother lode of kitsch, clamour and verve. She represents her own mostly black neighbourhood in vivid, jangling hues.

Or she did. Starting with the earlier iteration of the Met piece at the Hammer Museum in LA, Halsey distilled all that multicoloured history into a surface of pure pallor. Ancient Egyptians enlivened walls and temples, and even the Sphinx, in brilliant pigments, but time and convention have handed down an image of unblemished whiteness. Kara Walker gathered a similar set of associations in her 2014 "A Subtlety", a giant all-white statue of a black woman in a sphinx-like pose erected in a doomed sugar factory in Brooklyn. That work, too, was temporary, and addressed the intersection of race, whiteness, monumentality and the changing city. It's hard not to see Halsey's neo-antique temple, which dazzles with its sugar-cube glare, as a belated response to Walker.

As you move closer to its papery surface, you start to notice all the places where colour is implied. The faces on the sphinxes and column capitals belong to Halsey's relatives and friends. The walls are inscribed with the outlines of posters, signs, ads for hair salons, sketched-in bodybuilders and graffiti tags. "Stop Gentrification," one carved scrawl exhorts. "Black Workers Rising! For Jobs, Justice & Dignity" appears printed in white letters on a white flyer that's plastered on white brick. It's as if Halsey had created a 3D colouring book, begging to be brought to life with crayons or magic markers. (Best not to try that at the Met.)

The tension between colour and whiteness animates Halsey's temple, and so does the ambiguity between fragility and permanence. The Hammer version (called "The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (Prototype Architecture)") was made of cardboard, gypsum and paint, the stuff of theatrical sets that are built to be struck and eventually scrapped. The Met version is composed of 750 glass-fibre-reinforced concrete tiles on a steel armature — not quite as perennial as stacked blocks of stone, but durable all the same. That doesn't mean it will hang around the museum forever; in the fall it will be dismantled and shipped back to California, ready for a future as a local landmark.

LA's historically black areas are constantly under threat — from racism and neglect, changing demographics and covetous real-estate interests. Having always resented the physical evidence of that unease — cheap siding, barred windows, barbed wire and bare yards — Halsey saw the study of architecture as a way to supply alternatives, "a space of pleasure . . . a spiritual space where we could feel free". It seemed natural to go looking in the iconography of ancient Egypt, which has acquired mythic status as a wellspring of black culture.

Working to retain a neighbourhood's racial identity in the face of overwhelming change may be quixotic, but LA's activists are trying — fully aware that they are simultaneously contributing to its transformation. A decade ago, the guerrilla gardener Ron Finley started commandeering sidewalk medians as public vegetable gardens. Halsey has pursued her own urban revitalisation strategy, transforming a warehouse into a community centre and food distribution hub. "We're fighting, as we always have, for space and the future of our neighbourhoods. How do we refuse to be displaced, assert our autonomy, and survive?" she asks.

Those efforts help people right now and every day, but they also make the area more appealing to the very newcomers the activists would like to keep at bay. (Even the nomenclature is in dispute: the neighbourhood once known as South Central has been rebaptised South LA in the hope of cleansing its associations with poverty and crime.) The black community's cultural guardians are also trying to memorialise their presence for the future. Finley helped turn a mile-long stretch of Crenshaw Boulevard into Destination Crenshaw, a $100mn corridor or public art terminating at the soon-to-open Sankofa Park. Halsey's Egyptian temple, if and when it goes up in the same part of the city, will stand as a monument with a defiant message: gentrify this.

To October 22, metmuseum.org

Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment