New books on Tutankhamun

David Tresilian , Tuesday 7 Mar 2023

Last year's centenary of the discovery of the tomb of the ancient Egyptian golden boy-king Tutankhamun has led to a round of competition among publishers, writes David Tresilian

The discovery of the tomb of the ancient Egyptian golden boy-king Tutankhamun by British archaeologist Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings in Luxor in November 1922 has led to a raft of new titles about the king and his tomb by English-speaking and other Egyptologists.

Publishers have been competing to mark the centenary, with books appearing on everything from the tomb and its contents and the biography of the young Pharaoh for whom it was made to the story of the man who found it and the afterlife of the discovery.

Carter published his own version of the discovery even before he had finished clearing the objects from the tomb for display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. One hundred years later, what new material do the new books hold that have been issued to mark the centenary?

The raft of new books certainly bears witness to a new diversity in the questions asked about the discovery, with their authors being as likely to write about those that made it and the different meanings of Egyptology as a field of study as they are about what the tomb can tell us about its long-dead owner. Some of them also do not hesitate to tell us a lot about themselves.

Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive edited by British Egyptologist R B Parkinson and published by the Griffith Institute in Oxford in the UK is in some ways typical of this new interest in the development of Egyptology and the place of Carter and his aristocratic patron Lord Carnarvon in it.

Produced to accompany an exhibition of the same name held last year, it re-examines materials deposited at the Institute after Carter's death by his niece Phyllis Walker and consisting of his notebooks, letters, and private diaries about the excavation of the tomb. It casts light on the day-to-day issues confronting early 20th-century Egyptologists, at least those working in the field, and it helps readers to understand what was going on behind the scenes during and after the discovery.

In his introduction, Parkinson explains how the archive came to be in Oxford and gives a sketch of its contents. Much of it is also available on the institute's website, which includes digital images and transcriptions of Carter's dig diaries and journals for the years leading up to and after the discovery. There are some 3,500 cards bearing descriptions by Carter of materials found in the tomb and over 1,000 photographs taken by Harry Burton, the American photographer whose famous photographs of the excavation fixed its image worldwide.

Staff at the institute chose 50 objects from the archive for the exhibition, and these are reproduced with accompanying commentary in the book. There are letters, diaries, drawings, maps and photographs bearing witness to Carter's activities in Egypt before and during the excavation of the tomb, and there are many of Burton's famous photographs. These were taken using glass plates coated with silver and gelatin emulsion that were exposed for up to several minutes but nevertheless yielded astonishingly clear high-resolution prints.

Some of the photographs show the arrangement, or disarrangement, of the objects in the tomb when it was discovered, with some of them being piled up in corners or swept together in heaps as the ancient Egyptian priests hurriedly repaired the damage of several break-ins before resealing the tomb. There are now-iconic images of Carter at work in the tomb, and there are others that bear witness to the decisions of those that built it.

The ancient Egyptian workman produced some of the tomb furniture in "flatpack" form, for example, leaving ink markings on it to show how it should be reassembled in the tomb. However, in the case of the gilded shrines designed to be re-erected around the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun in the burial chamber they made a mistake in the measurements, meaning that the shrines had to be reassembled in the opposite direction to that originally intended.

In the nested coffins containing the boy-king's mummy, Carter found withered garlands of cornflowers, blue lotus, and olive and willow leaves placed by the ancient Egyptian priests at the moment of burial in a gesture of mourning. These "few withered flowers still retaining their tinge of colour" were among the most poignant objects in the tomb, Carter wrote in his book on the discovery.

Also found were objects — items of furniture, jewellery, domestic items — that showed signs of wear as if they had been favourite objects that Tutankhamun had been attached to in life and that had accordingly been selected to be interred with him in his tomb.

SHAPING A CENTURY: Parkinson writes in his introduction to Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive that the Oxford Carter archive, however intriguing, might be thought to give a "highly partial view of events".

The discovery is seen entirely through the eyes of Carter and his associates, he says, and "the lack of [modern] Egyptian voices in the archive starkly reveals the inequalities of power in both the social and academic worlds" of Carter's time.

The theme of the story of the discovery sometimes being used to "uncritically endorse a nostalgic story of a golden age of archaeology" in Carter's time is one of the ideas also examined in US Egyptologist Christina Riggs's Treasured: How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century, a wide-ranging examination of different aspects of the afterlife of Tutankhamun since the discovery of his tomb a century ago.

Riggs, an academic in the UK, is the author of a clutch of well-regarded books on different aspects of Egyptology including Unwrapping Ancient Egypt, an exploration of the wrapping techniques used for sacred objects, including mummified bodies, in ancient Egypt, and Photographing Tutankhamun, a book about the photographs taken by Burton and others of the tomb and its contents. In her new book, she writes on the discovery and clearance of the tomb, but also on the subsequent exhibition of the objects in Egypt and abroad and on the ways in which Tutankhamun and his tomb have been used for commercial and other purposes.

Many stories jostle for attention in Riggs's book, including the author's own, as she begins by writing on how she first became aware of ancient Egypt and Tutankhamun at primary school in the US in the 1970s, later deciding to make Egyptology a career. Her book "recounts my own discovery of Tutankhamun," she says, being "a reckoning of what I've learned and unlearned since that jewel-like coffin flickered into view upon a classroom screen" decades ago and particularly "of how different people, at different times and places, have imagined ancient Egypt."

Among those people are Carter and Carnarvon, of course, the discoverers of the tomb, but also many others, including Christiane Desroches Noblecourt, the French Egyptologist who arranged the first major tour of the objects from Tutankhamun's tomb abroad in the 1960s, and many other lesser-known figures who arranged similar tours in the 1970s and later.

Noblecourt's triumph was the 1967 Paris exhibition of objects from Tutankhamun's tomb, the first time so many of them had been seen outside Egypt. It was the precursor of a string of later shows that included similar exhibitions at the British Museum in London in the 1970s and then a tour of the US where the objects from the tomb were given pride of place at exhibitions in New York and Washington.

Riggs also brings the story right up to date with a consideration of international tours of objects from the tomb over the last decade as well as of the transfer of the ancient Egyptian royal mummies from the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation (NMEC) in 2021 and the new Tutankhamun galleries at the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) on the Pyramids Plateau.

Interwoven into this material are considerations on Egyptian and international politics, the economics of tourism, and the history and present character of the Egyptology profession as well as the continuing public interest in material on Tutankhamun worldwide. One of Riggs' strongest chapters may be that on the US tour of objects from the tomb in the 1970s, when different agendas came together to ensure its success.

Having seen the crowds at the Paris and London exhibitions, curators in the US pulled out all the stops, including diplomatic ones, to ensure that Tutankhamun and his treasures would visit the US. In Egypt, the focus was on "the pride and possibilities the vast American operation represented… in seeing Egyptian culture acclaimed in the United States," with millions expected to see the exhibition at one of multiple venues or to watch the visit on television.

There was great interest in the tour among African-Americans, some of whom saw Tutankhamun's visit as an opportunity to raise the issue of race in museum exhibitions in the US and the African character of ancient Egyptian civilisation, a theme explored by the Senegalese scholar Cheikh Anta Diop. Then US president Jimmy Carter visited the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, along with other leading figures from politics and the arts. Tutankhamun became a kind of cultural ambassador of modern as well as ancient Egypt and a "beautiful cultural bridge" between Egypt and the US during the latter's bicentennial celebrations, as the Egyptian ambassador in Washington put it at the time.

"For all the cultural complications and hackneyed stories attached to the history of Tutankhamun and his tomb, and all the inaccuracies, oversights, and bland superlatives that every iteration of the tale repeats, nearly everyone can agree on this: there is genuine wonder in the burial of this young man and the wealth of objects that were found with him," Riggs writes.

"My childhood encounter with Tutankhamun shaped what became a privileged career… In the hundred years since he was brought back to life, Tutankhamun has been an inspiration to hundreds of children who, like me, needed something outside the everyday to raise their eyes just high enough to see over the limitations of life."

CHANGING THE WORLD: There are similarities between Riggs' approach and that of US Egyptologist Bob Brier in his Tutankhamun and the Tomb that Changed the World.

Brier is the author of multiple books on ancient Egypt, including several about Tutankhamun, most of them aimed at a popular audience. His new book is no exception, being written in an attractively chatty style and doing a good job of updating general readers about intriguing recent developments in Egyptology.

Even if not everyone will agree that Tutankhamun's was a tomb that changed the world, as the title of Brier's book claims, few readers are likely to come away from it without agreeing that the tomb at least changed the world of Egyptology. When it was discovered in November 1922, many Egyptological excavations were still in the hands of amateurs, with the British aristocrat Lord Carnarvon, who held the concession to excavate in the area of the Valley of the Kings in which the tomb was found, and the US businessman Theodore Davis, who had held the concession before him, being fairly typical of the field.

Carter's discovery changed all that as a result both of his own high standards and the unprecedented demands made by the clearance of the tomb. As Brier explains in the first section of his book, Carter's work set the standard for all subsequent excavations, notably with regard to the care with which the objects in the tomb were recorded and preserved, often requiring new chemical procedures to preserve fragile organic materials and arrest processes of decay. In this respect the discovery forced all subsequent excavators to up their game, even if some earlier practitioners had also insisted on the need to keep careful records and adhere to established procedures in the field.

However, there was another respect in which the discovery changed the world of Egyptology, Brier writes, and one that was at least at first more difficult for some foreign Egyptologists to accept. Carter's discovery was made at the height of the Egyptian nationalist movement following the 1919 Revolution, and the clearance of the tomb, undertaken by Carter almost from the day after the discovery, was punctuated by the end of the British protectorate over Egypt and the establishment of an independent kingdom. Politics in Egypt were changing, and the new government was less likely to accept the former practice of sharing the finds made by foreign excavators between the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and the funders of the excavations abroad.

To their chagrin, Carter, and, until his early death in April 1923, Carnarvon, discovered that they could no longer behave as they liked in the Valley of the Kings, notably when it came to taking control of the excavation and clearance of the tomb and appropriating a portion of the finds themselves. The discovery, Brier writes, "played a significant role in changing the political landscape of Egypt… [since] both the tomb and the boy-king became rallying points for Egyptian nationalists and their efforts to end British rule in Egypt." While it is true that many people, not only Egyptian nationalists, were irritated or worse by Carter and Carnarvon's proprietorial attitude to the discovery, it would probably be more accurate to say that this constituted simply another irritation rather than the cause of the nationalist movement.

While Brier's re-examination of this history is useful, perhaps the main appeal of his book lies in his account of the research subsequently carried out on the objects found in the tomb. In the book's second and third parts, he fills contemporary readers in on some of the latest thinking on traditionally unsolved questions regarding Tutankhamun and his tomb, including what sort of Pharaoh he was, how he died, and what to make of some of the ambiguities of his tomb.

Working from X-rays of the mummy of Tutankhamun, some early investigators believed that he could have died from a blow to the back of the head since they seemed to indicate damage consonant with it. Even Brier seems to have thought so at one stage, since he used the X-ray evidence to support his theory that Tutankhamun was murdered, explained in his 1999 book The Murder of Tutankhamun. Now, however, Brier and others have had to amend their views since more recent CAT scans of the mummy have shown that there had been no blow to the back of the head. "Tutankhamun may still have been murdered," Brier writes, "but it wasn't in the way I thought."

Recent CAT scan evidence has also allowed investigators to build up a better picture of Tutankhamun in life, though here the evidence is less clear-cut. While X-rays only allow high-density material such as bone to be investigated, CAT scans can be used to investigate soft tissues as well, including the desiccated tissues of ancient Egyptian mummies.

One new finding from the CAT scans is that Tutankhamun may have had a club foot and that he may have walked with a pronounced limp, explaining the presence of 130 "walking sticks" in his tomb. He may also have died as a result of an infection from a broken leg. Brier is sceptical about this new evidence, believing it does not allow for the drawing of any firm conclusions.

Like Riggs, he has some pages on the afterlife of Tutankhamun in the shape of the blockbuster exhibitions inaugurated with the 1967 Paris show and reaching an early peak with the New York and Washington shows in the 1970s. He writes amusingly of the rivalry between John Carter Brown, director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and Thomas Hoving, legendary director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Hoving "wanted to do for the Metropolitan Museum what [the popular musical] Jesus Christ Superstar did for the Bible," and Tutankhamun was part of his plans. The museum gift shop made a lot of money out of replicas of tomb artefacts and other souvenir items about Tutankhamun, and much of this was sent to Egypt.

CENTENARY OF TUTANKHAMUN: UK Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves is given some respectful pages in Brier's book, even if the theory with which he has been most associated has not stood up to scientific investigation.

Looking again at the painted north wall of the burial chamber of the tomb, Reeves decided that there could be further hidden rooms behind it, perhaps even the final resting place of the woman who may have been Tutankhamun's mother, queen Nefertiti. However, as Brier notes, subsequent investigation, including ground penetrating radar studies of the rock surrounding the tomb, have not supported this conclusion.

Nevertheless, as Brier also notes Reeves is the author of books to which generations of amateur and professional Egyptologists have referred when looking for an authoritative modern account not only of the tomb of Tutankhamun but also of the Valley of the Kings more generally. His Complete Tutankhamun first appeared in 1990, and a sumptuously illustrated new edition has now been published to mark the centenary of the discovery.

All Tutankhamun fans will want to read the new edition of Reeves's book, even if, weighing in at well over a kg and of artbook size, it is best kept at home as a coffee-table book rather than employed as a real-time guide to the tomb. The publishers seem to have spared no expense in filling it with high-quality illustrations, and these alone, when added to Reeves's text, completely revised for this edition, provide hours of fascinating perusal.

Reeves says in his introduction that since the first edition of the book was published three decades ago there have been major advances in our knowledge of Tutankhamun and his tomb, partly to do with new technologies such as CAT scans and DNA analysis and partly to do with new and more careful attention being paid both to Carter's excavation records and to the materials that were found in the tomb. He is alive to the controversies outlined by Brier, reporting much of the same evidence, but his book has a much wider scope. It is hard to imagine any reader not taking away fresh nuggets of intriguing information from it.

Reeves has also added to his account of Carter, retaining the overall admiration for the man and his methods that was evident in the first edition of his book but tempering this with a more realistic account of his failings. Carnarvon does not emerge well from Reeves's account, which is more alive to the political situation in Egypt at the time of the excavation. The chip that Carter seems always to have had on his shoulder as a result of his being deprived of a proper education while being surrounded throughout his life by the rich or very rich is now seen as having interfered with his professional work. The book also contains new material on objects illicitly lifted by Carnarvon and Carter from the tomb.

Reeves writes clearly and authoritatively, and for the general reader at least there do not seem to be any aspects of the tomb and its contents that he does not consider, even down to minute descriptions of tomb contents often overlooked in other accounts. Of Tutankhamun's collection of "walking sticks", Reeves says that these do no indicate anything about his mobility or general health since they were probably used for ceremonial purposes.

There is still a lot more that can be learned from the tomb and its contents, he says, even if some have in the past been disappointed by the absence of documentary evidence such as papyrus scrolls in it. "Resistant to the glitz that so distracted in the past, the focus now is not on what we don't have but on the extraordinary and scarcely perceived depths of information the tomb does contain — if we care to look," Reeves comments.

He spends several pages rehearsing his theory that the tomb of Tutankhamun that we know today, and that Carter thought he had completely excavated, is in fact only part of a larger tomb complex that includes, hidden behind the walls of the burial chamber, further rooms and corridors in which queen Nefertiti may be buried. He seems unbothered by the CAT scan and other evidence reported on by Brier.

While the rest of this fascinating book expertly presents the modern consensus on Tutankhamun and his tomb and the results of recent research, on the latter point readers will have to draw their own conclusions.

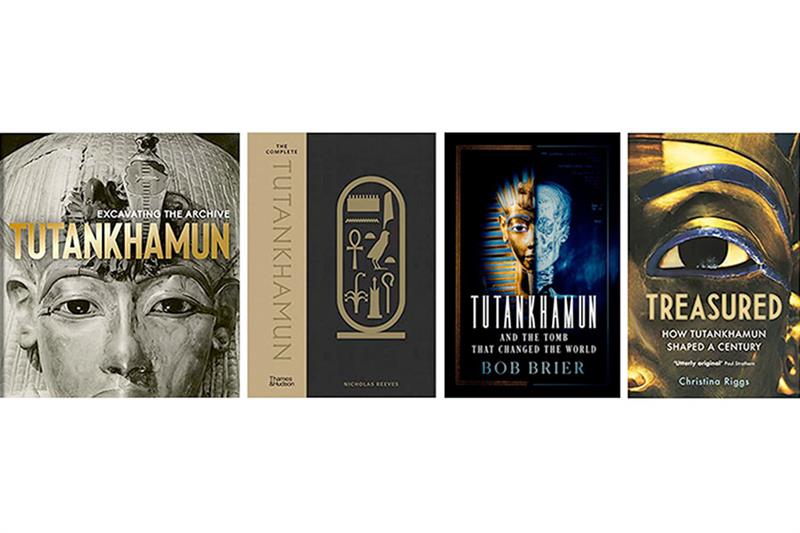

R.B. Parkinson, Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive, Oxford: Griffith Institute / Bodleian Library, 2022, pp 144; Christina Riggs, How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century, New York: Public Affairs, 2022, pp 426; Bob Brier, Tutankhamun and the Tomb that Changed the World, New York: Oxford University Press, 2023, pp 320; Nicholas Reeves, The Complete Tutankhamun: 100 Years of Discovery, London: Thames and Hudson, 2022, pp 464.

* A version of this article appears in print in the 9 March, 2023 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment