https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/feb/08/the-mystery-of-a-gods-tomb-archive-1969

From the Guardian archive

Egyptology

The mystery of a god's tomb – archive, 1969

8 February 1969: Out of this temple came enough "objects" to put a new museum of Egyptology on the map

Walter Schwarz

Fri 8 Feb 2019 00.30 EST

Last modified on Fri 8 Feb 2019 05.36 EST

Funerary monument to King Zoser, the 'Step Pyramid', Saqqara, Egypt.

Photograph: DEA / W. BUSS/De Agostini/Getty Images

The whisper in Cairo was that Professor Walter Emery of London University, while digging among the Sakkarah pyramids, had found, or thought he had found, the tomb of Imhotep.

Imhotep, brilliant architect of the Pharaoh Zosers "Step" Pyramid at Sakkarah; Grand Vizier; doctor; sage; and magician, is remembered as the outstanding genius of ancient Egypt. Two thousand years after he died he became god of medicine. The Greeks, identifying him with Asklepios, worshipped him as the god of healing.

If Emery really had found Imhotep, it would be the biggest thing since Carter found Tutankhamun – and a dazzling funereal haul besides – in 1922. It would thrill philosophers and theologians as much as historians, and even GPs.

However, Emery was said to discourage visitors. He was further said to have dug up so many objects of bronze and gold, none less than 20 centuries old, that no one was allowed near the place without a permit from the Ministry.

Anyway, I took a taxi out to Gaza and from Sheikh Abu Aziza's admirable stable of 70, hired two slender Arab stallions and a stable boy, and set off for Sakkarah.

Sure enough the Emery site was out of bounds, even to horsemen arriving from an unorthodox direction. I sent in a note, and a Dr Martin sent one back, saying that unfortunately Professor Emery was away.

On Tuesday this week, without a horse but with a permit from the Ministry, I returned to Sakkarah. In the cool courtyard of the Emery residence I found Mrs Emery, photographing bronze and gold figurines against a yellow sheet in the sunshine. While someone went to find "the prof" I was shown the magazine – the locked shed where the "objects" are stored.

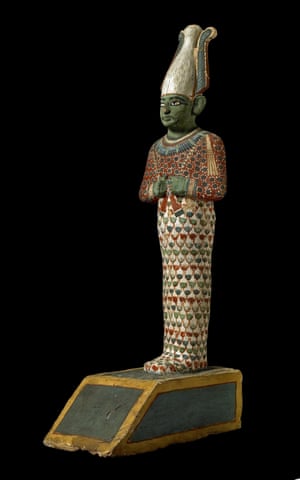

A painted wooden statuette of the God Osiris, ruler of the netherworld and judge of the dead. Photograph: British Museum/PA

What they had unearthed, right at the beginning of the season in November, was the site of a temple dedicated to Imhotep in the fourth century BC – two thousand years after Imhotep's death. Judging by the graffiti scrawled unceremoniously on the walls by generations of visiting pilgrims, it had been a kind of Lourdes, where people hoped Imhotep would cure them of their afflictions.

Out of this temple came enough "objects" to put a new museum of Egyptology on the map. Statuettes by the hundred. A magnificent figure of the God Osiris, in bronze inlaid with gold, looked less shop-soiled after six millennia than it would have done after as many months in a dealer's window. As for the hinged wooden box which housed it – I have boxes in my attic that show more signs of age.

There are gods and animals, naked children with flowing pigtails, queens suckling their babies. Some, like a figure of a running dog, have the clean, elongated look that seems to belong more to the twentieth century AD than any other. And there was a figure of Imhotep himself, wise-looking and inscrutable.

What about the tomb? An assistant of Emery's said guardedly that this had turned up only last week and not much could yet be said of it. We walked across half a mile of sand to see it. Behind the temple area they had uncovered two subterranean galleries, each a hundred yards long. In caches along the walls they had found mummified baboons and ibis birds, both of which were part of the Imhotep cult.

While work was going on in the galleries someone had scratched around on top and found the tops of four walls. These are indubitably the superstructure of a Third Dynasty tomb – contemporary with the Step Pyramid which Imhotep had built for Zoser only half a mile away. All the workers – 220 of them – were immediately moved from the galleries up to the new tomb. There they still dig – a race against time, because the season, and the money, runs out on March 13.

Is it really Imhotep's? I was invited into the house, and, over a well-cooled beer, talked it over with the prof. What evidence there is, he said at the outset, is circumstantial. No inscription had yet been found. But this was not surprising, since Christian regimes of later centuries had deliberately obliterated the temple, and built a new village on top of it. The Christians would also have obliterated what was visible of Imhotep's tomb.

"You have to remember that Imhotep died a mortal man, not a god," Professor Emery said. "He would have been buried in the vast Sakkarah cemetery area, among other 3rd Dynasty nobles. This tomb is right over the temple; we hope the burial shaft will connect with the galleries.

Egypt's 4,600-year-old pyramid of Zoser: a history of cities in 50 buildings, day 1

Read more

"They built the temple 2,000 years later; might they not have built it where they knew, or thought, Imhotep himself was buried? The ibis birds and the baboons were in the galleries, not the temple."

There is another clue. Classical sources say Imhotep was buried near a lake of crocodiles. Well, there was a lake here - the Lake of Abusyr – until very recently.

Since you're here…

© 2019 Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies.

Since you're here…

… we have a small favour to ask. Your support enables The Guardian to shed light where others won't. It emboldens us to challenge authority and champion the public interest. Contributions from readers power our work, giving our reporting impact and safeguarding our essential editorial independence. This means the responsibility for protecting independent journalism is shared, empowering us all to bring about real change around the world. Thanks to our supporters, Guardian journalists have the time, space and freedom to report with tenacity and rigour. We have chosen an approach that allows us to keep our journalism accessible to all, regardless of where they live or what they can afford. This means we can foster inclusivity, diversity, make space for debate, inspire conversation – so more people, across the world, have access to accurate information and inspiring ideas with integrity at its heart.

The Guardian is editorially independent, meaning we set our own agenda. Our journalism is free from commercial bias and not influenced by billionaire owners, politicians or shareholders. No one edits our editor. No one steers our opinion. This is important as it enables us to give a voice to those less heard, challenge the powerful and hold them to account. It's what makes us different to so many others in the media, at a time when factual, honest reporting is critical.

Every contribution we receive from readers like you, big or small, goes directly into funding our journalism. This support enables us to keep working as we do – but we must maintain and build on it for every year to come. Support The Guardian from as little as $1 – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment