Ancient Egyptian Healthcare Was 'Advanced and Successful,' Say Experts

Jan 14, 2024 at 5:00 AM EST

By Aristos Georgiou

Science and Health Reporter

Ancient Egyptians' healthcare system was "advanced and successful" for its time, the authors of a new book on the topic have said.

Medicine and Healing Practices in Ancient Egypt by researchers Rosalie David and Roger Forshaw takes a fresh perspective on healthcare practices in the land of the pharaohs thousands of years ago.

We wanted to look at ancient Egyptian medicine and healing methods from a different perspective," the researchers, affiliated with the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, told Newsweek.

"Whereas previous accounts have mainly focused on various diseases, health complaints and treatments as recorded in the inscriptions and palaeopathological record, our book provides a 'people-focused' interpretation, essentially looking at how the system worked for the healthcare providers and their patients," they said.

The care system included "pharmaceutical treatments" involving recipes created from minerals, plant ingredients and animal parts; basic surgery and pragmatic treatments, such as bandaging broken limbs; and to, a much lesser extent, "magical" remedies.

These treatments were universally available to men, women and children from all levels of society, according to the researchers."This universal approach, together with an enlightened attitude towards deformity and disability and provision of care for the elderly/infirm, was an encompassing system that worked well for the ancient Egyptians for over 3,000 years," the researchers said.

In a press release, David, an emeritus professor of biomedical Egyptology, said: "The Egyptian healthcare system was advanced and successful, not least for devising innovative ways to treat snake bites and save lives. Its achievements although widely praised in antiquity, are often not fully recognized today. This ancient Egyptian medicine was even evident in medieval and later practices in Europe, and some aspects still survive today in modern 'Western' medicine."

How did the ancient Egyptian healthcare system work?

While researchers do not have a complete picture of life in antiquity, the available evidence suggests that individuals in ancient Egypt had some freedom to choose their healthcare providers.

Some healers would probably specialize in practical treatments, such as bandaging broken limbs or minor surgery, whereas others offered "magical" treatments, like reciting spells or laying on hands.

These choices were, to some extent, but not exclusively, dictated by the type of illness. For example, where the cause was obvious, practical treatment was prescribed; where the cause was not obvious, magic may have been used to destroy the "disease demon." In some instances, patients may have consulted both types of practitioners and pursued various treatments to seek a cure.

"Some physicians had a dual religious/secular role; they provided medical treatment and, as priests of deities associated with healing, spent part of each year performing daily rituals in temples and perhaps providing medical training there. Other physicians and health providers had secular or 'magical' roles and provided community treatment in towns and villages," David and Forshaw told Newsweek.

There is some evidence from inscriptions to suggest that people paid for care, although this was probably based on what they could afford, which meant treatments were not only reserved for the wealthy.

Some physicians and other health workers, such as midwives, visited patients' homes. However, some temple precincts also had centers where patients could undergo various treatments and therapy. Some doctors treated the injured on the battlefield and at mines and building sites. There were also palace physicians who attended to the king and royal family and senior administrators of the state who were based in the palaces.

The ancient Egyptians did not identify "diseases" as such—their medical documents describe individual case studies in which symptoms are listed. The likely outcome of the condition (curable, incurable, or uncertain) is sometimes discussed, and treatment (with ingredients where applicable) is often described.

Infectious diseases were sometimes attributed to a deity who had to be appeased with prayers or rituals, "disease demons" who acted on behalf of the deity, or the ill wishes of an enemy or deceased person who was jealous of the living.

Regarding mental illness, again, the ancient Egyptians recorded symptoms rather than identifying diseases. Some cases may indicate, for example, epilepsy or schizophrenia, but they are not classified as specific illnesses.

Dealing with disabilities, deformities and the elderly

Conditions such as blindness, loss of hearing, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis were all present in the older population, and the ancient Egyptians had pharmaceutical remedies designed to treat some of them. They also tried to combat the appearance of old age with various cosmetic treatments, such as improving wrinkled skin and dyeing greying hair.

Despite the relatively wide range of medical treatments available in ancient Egypt, some 90 percent of the adult population probably did not live far beyond the age of fifty, according to the researchers. The average age of death was even lower.

However, there were some notable exceptions, such as the pharaoh Ramesses II, who was thought to have lived to around the age of 90. Generally, though, "old age" to the ancient Egyptians would probably have meant the years from the mid-thirties onwards.

When it came to people living with deformities and disabilities, the ancient Egyptians had an "enlightened attitude" that was very different from contemporary societies, according to the researchers.

"Unlike the ancient Greeks, they did not expect everyone to have a 'perfect' physique. The Egyptians did not leave infants with disabilities to die, and the society provided healthcare where required, whether the condition was the result of genetic conditions, congenital abnormalities, accidents or injuries," the researchers said.

"In the social context, individuals with disabilities were not banned from working in temples, and careers were identified to provide livelihoods for some groups—for example, for the blind, playing the harp. Some groups (for example, dwarfs) were regarded as representative of physical 'otherness' rather than deformity."

Treating snake and scorpion bites

Snake and scorpion bites would have been among the various medical problems the ancient Egyptians regularly dealt with. One piece of evidence the book discusses is the Brooklyn Papyrus, a guide for specialist priests called upon to treat individuals suffering from such afflictions.

The papyrus, dated to around 450 B.C., making it one of the oldest preserved writings about medicine, describes various snakes, their habitats, the symptoms of their bites, and the deity of whom the serpent was believed to be a manifestation.

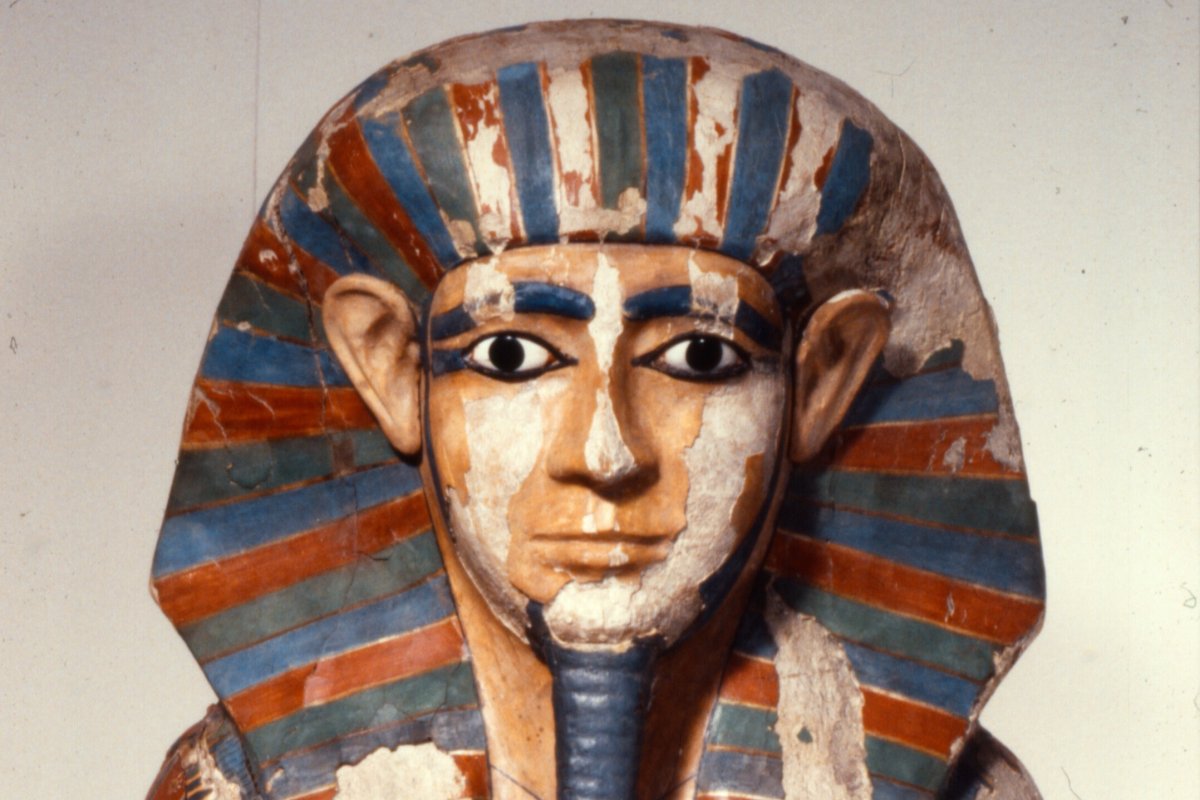

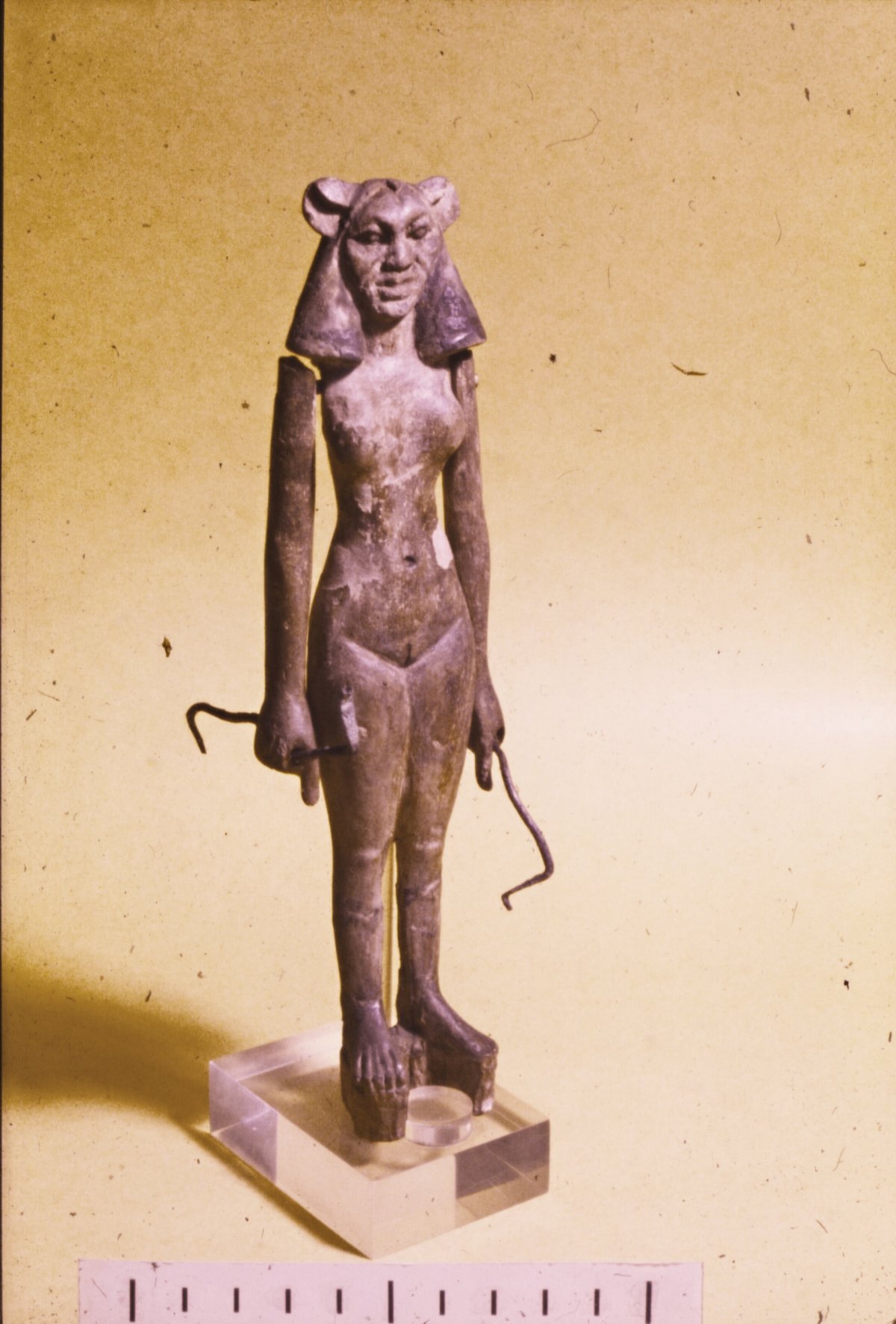

A statue of Sekhmet, goddess of medicine, from the Temple of Karnak (c. 1400 B.C.) in Luxor. Snakes and scorpions were both good and evil, and therefore had to be appeased through deification and worship. The University of Manchester

The document also describes treatments for the bites, some of which were painful but potentially effective (the papyrus also contains information on treating scorpion and spider bites). These treatments include incision of the wound with a knife to relieve tissue fluid and limit the absorption of venom, as well as the administration of (mainly herbal) drugs.

Among the drugs the Egyptians used for these purposes is a naturally occurring compound called natron, which can be found in saline lake beds in arid environments. This compound is capable of reducing swelling, and it also acts as an antiseptic for wounds and cuts.

On a less practical note, the Egyptians also used magical incantations to cure the effects of bites, some of which were specific to certain types of snakes.

Ancient Egyptian medicine today

Although the ancient Egyptians had a life expectancy similar to that in other societies before the discovery of antibiotics, they had a range of treatments—some still valid—that would have effectively alleviated various ailments, the researchers said.

For example, the Egyptians had some successful treatments for amputations and wound healing. They also used reproducible and viable pharmaceutical therapies some 1,800 years before the ancient Greeks.

"Until recent studies demonstrated this, the Greeks were accredited as the founders of the pharmaceutical tradition," the researchers said.

Several elements of ancient Egyptian healthcare still survive today in Western medicine. Among these is a treatment for a dislocated jaw first recorded in the Edwin Smith Papyrus, dated to around 1600 B.C., which is considered to be the oldest known surgical treatise on trauma.

"The technique has a long history: referred to by Hippocrates, evident in Europe in the Middle Ages, and today's practitioners—being the recipients of such knowledge—still utilize exactly this procedure," the researchers said.

Surgical techniques such as suturing, or stitching, were first referred to by the ancient Egyptians, as was the use of certain medical instruments like scalpels, according to David and Forshaw.

Like today, the ancient Egyptians also had specific guidelines to define and protect the relationship between healthcare providers and their patients. In addition, healers provided some level of care and treatment for all their patients, regardless of the severity of the condition. Appropriate palliative care was offered even to those considered to be terminally ill.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, mental health, and psychology-related stories. Aristos joined Newsweek in 2018 from IBTimes UK and had previously worked at The World Weekly. He is a graduate of the University of Nottingham and City University, London. Languages: English. You can get in touch with Aristos by emailing a.georgiou@newsweek.com.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment