The statue, viewable at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, the flagship museum of National Museums Scotland, has remained a mystery to generations of Egyptologists because it should be impossible; by the strict conventions ruling every aspect of Egyptian life, a commoner could not, at any time, touch a reigning king, let alone be in such intimate contact. For centuries, to carve such an act in stone would be considered heresy.

"The instant I saw it, I thought: 'That statue shouldn't exist'," says Margaret Maitland, the principal curator of the ancient Mediterranean at NMS. "It blew my mind."

But Maitland has managed to decipher the ancient statue. In doing so, she has named the faceless man and, for the first time, identified a whole group of sculptures, including in other major museums, that have never been categorised together before.

Ensuring immortality

The statues, Maitland discovered, all hail from the same remarkable site in Egypt: Deir el-Medina, a desert village of craftworkers who designed, built and decorated the tombs that ensured the pharaohs' immortality. In doing so, they were privy to their rulers' most intimate secrets.

Maitland joined the NMS in 2012 and made the discovery while working on the redisplay of the museum's Egyptian collection in the Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery. She presented her research at an international conference on Deir el-Medina at the Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy.

Before her research, curators at NMS had interpreted the statue as depicting a tutor with a royal child, while the Victorian archaeologist who first excavated it thought it was a king nursed by the goddess Isis—even though the small figure wore a crown, while the larger figure was definitely a man.

"The statue clearly shows a crowned king, but a normal person would never be shown in three dimensions with a ruler," Maitland says. "For centuries, it was forbidden even to portray such a grouping in two dimensions in tomb paintings."

The statue became part of NMS in 1985 when the collection of the former National Museum of Antiquities, also in Edinburgh, merged with that of the Royal Scottish Museum. Before that, the statue was part of the collection of the pioneering but almost forgotten archaeologist Alexander Henry Rhind, who hailed from the town of Wick in the far north of Scotland and made his name excavating prehistoric sites in northern Scotland before travelling to Egypt for the first time in 1855. Rhind died in 1863, aged just 29, of tuberculosis. By revisiting his meticulous records, Maitland learned that Rhind had discovered and excavated the statue at Deir el-Medina.

As Ancient Egypt fell, the village was gradually abandoned and never rebuilt. But, at its height, the isolated community was full of prestigious, highly skilled and learned people who were well paid for their craft. Literacy was so common in Deir el-Medina that archaeological digs have uncovered thousands of shards containing sketches, messages, lists, complaints and jokes. The workers' temple, as well as their own tombs, have also been found buried in the sand.

Maitland's immersion into Deir el-Medina led to a discovery. The small figure depicted in the statue, she realised, was not a living pharaoh, but a statue of a pharaoh. The iconography of the larger man, kneeling as he is with outstretched arms, echoed other familiar depictions of an Egyptian figure presenting an offering.

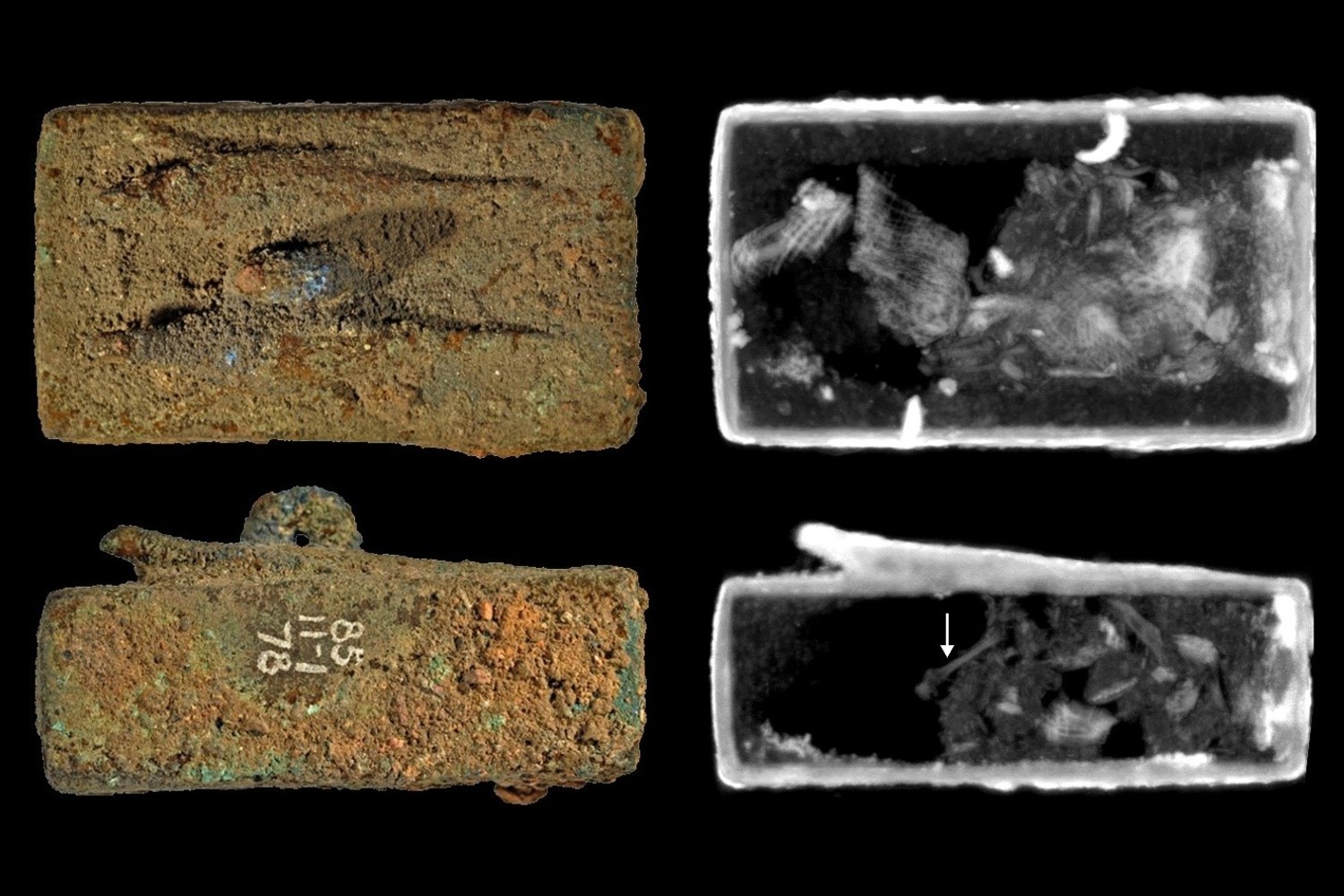

Maitland began to research all the other sculptures from Deir el-Medina and found a whole group, including a fragmentary but beautifully carved example in New York's Metropolitan Museum and several in the Egyptian national museum, some surviving as no more than the offering hands. A few in the group show the royal statue within a shrine, so in less intimate contact with the donor than the Edinburgh example.

Her conclusion is that the most senior workers at Deir el-Medina were uniquely permitted to not just build the tombs of the rulers—but to also offer statues to chapels in their own temple of Hathor, portraying themselves in the closest contact with these images of divine power and authority. This could not have happened without the knowledge of the royal court; every aspect of the work of the village was regulated and recorded, from the materials supplied to the food they ate and the beer they drank. These images were mutually beneficial, Maitland believes, reinforcing both the supreme power of the rulers and the loyalty and status of the village officials so intimately connected with them.

So, who is the faceless man and the statue of the child pharaoh? The kneeling donor wears a garland of flowers on his head. This was common in statues of women but very rare in depictions of men—except for a period during the reign of the Ramesses kings, Maitland found.

Ramesses II, known as 'Ramesses the Great', reigned from 1279-1213BC, the second longest reign of any ancient Egyptian king. His image was ubiquitous, for he erected more temples and statues honouring his own glory than any other Egyptian ruler. The highest village official at Deir el-Medina, and the direct link with Ramesses' court, would have been an official known as the vizier, but the statue does not show the robes typically worn by such a senior figure.

The next in line—and, Maitland believes, the man who would have commissioned the statue—would have been the senior scribe, who was responsible for the crucial inscriptions on the tombs. If Maitland's identification of Ramesses II is correct, we know his scribe was a man named Ramose, for his tomb still survives. Ramose, then, has achieved his own immortality—in a gallery in Edinburgh.

Internecine squabbles among Egyptologists are common and knocking down a new theory a favoured sport. But, so far, Maitland's work has been accepted. "There is more work to do," she says. "I am haunted by the idea that the missing inscription—maybe even the missing face—may still lie in the sand waiting to be found, to prove or explode my theory."