Newsletter Osirisnet Janvier - January 2022

Un centre administratif pour les expéditions minières découvert dans le sud du SinaïHeadquarters of Ancient Egyptian mining mission found in Sinai

Photos: Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (MoTA)

Une mission archéologique égyptienne a mis au jour les vestiges d'un bâtiment utilisé comme centre administratif pour les expéditions dans les mines de cuivre et de turquoise du sud Sinaï. L'édifice, datant du Moyen Empire et construit en grès, a été découvert à Wadi el-Nasb, à 6 kilomètres à l'ouest du site de Serabit el-Khadim, à proximité des carrières de turquoise et du temple de la déesse Hathor. Le bâtiment était encore fonctionnel à l'époque romaine.

L'édifice s'étend sur 225 mètres carrés. Il est situé près du puits principal qui alimentait autrefois en eau la zone minière. Il se compose de deux pièces principales, de deux autres pièces et d'un escalier menant au toit. Le sol est fait de dalles de grès.

La fonderie de Wadi el-Nasb était la plus grande de l'Égypte ancienne sur la péninsule du Sinaï et produisait environ 100.000 tonnes de scories de cuivre (par an ?). Par ailleurs, le site comporte des inscriptions importantes datant du Moyen et du Nouvel Empire

Vous pouvez lire avec profit sur notre site : Les mines de cuivre de Timna

The remains of a unique sandstone edifice that was once used to supervise the mining missions for copper and turquoise in south Sinai more than 4,000 years ago, have been discovered. The edifice was unearthed in the Wadi Al-Nasb area, six kilometres west of the Serabit Al-Khadim site, near the turquoise mines and the temple of goddess Hathor, the lady of turquoise. It was built during the Middle Kingdom and continued to be used during the New Kingdom and then again during the Late Roman period.

The mining mission's premises is located in the center of Wadi Al-Nasb, overlooking the ancient main well that once supplied water to the mining district, and measures 225 square metres. The building consists of two main halls, two rooms and a staircase leading to the roof of the building.

Wadi Al-Nasb was the largest ancient Egyptian smelting site on the Sinai Peninsula, with an amount of copper slag estimated at 100,000 tons (per year?). In addition, Wadi Al-Nasb is a very important archeological site famous for its unique rock inscriptions from the Middle and New Kingdom.

You may wish to read about the mines (on our site): The copper mines of Timna

Découverte d'une vaste tombe gréco-romaine à AssouanDiscovery of a large Greco-Roman tomb in Aswan

Photos: Egyptian-Italian Mission at West Aswan (EIMAWA)

Un très grand tombeau familial, jusqu'alors inconnu, a été découvert à Assouan par la Mission égypto-italienne à Assouan Ouest (EIMAWA), dirigée par Patrizia Piacentini, professeur à l'université de Milan. La découverte a eu lieu dans la zone entourant le mausolée de l'Aga Khan, sur la rive ouest du Nil, où se trouvent plus de 300 tombes datant du sixième siècle avant Jésus-Christ au quatrième siècle après Jésus-Christ.

La dernière trouvaille est une grande tombe datant de la période gréco-romaine, qui, bien que pillée dans l'Antiquité, contient encore une vingtaine de momies et de nombreux matériaux intéressants. La tombe présente des traces importantes d'un incendie mystérieux. Un énorme dépôt contenant des ossements d'animaux (principalement du mouton), des fragments de poterie, des tables d'offrandes et des dalles inscrites en hiéroglyphes recouvrait le mur est de la structure, suggérant son utilisation comme site votif.

A very large, previously unknown family tomb has been discovered in Aswan by the Egyptian-Italian Mission in West Aswan (EIMAWA), headed by Patrizia Piacentini, professor at the University of Milan. The discovery was made in the area surrounding the Aga Khan's mausoleum on the west bank of the Nile, where there are more than 300 tombs dating from the sixth century BC to the fourth century AD.

The latest find is a large tomb dating from the Greco-Roman period, which, although looted in antiquity, still contains about 20 mummies and many interesting materials. The tomb shows significant traces of a mysterious fire. A huge deposit containing animal bones (mainly sheep), pottery fragments, offering tables and slabs inscribed in hieroglyphics covered the eastern wall of the structure, suggesting its use as a votive site.

A staircase partially flanked by carved blocks and covered by a mud-brick vault leads to the entrance, which was closed by a complex system of slabs and stone blocks found at the original site that had been erected above the staircase. The tomb has a hall with four burial chambers cut deep into the rock. In the hall, archaeologists found a terracotta sarcophagus containing the mummy of a child, and in the chambers, nearly 30 mummies, some in an exceptional state of preservation, others cut up by former thieves. Radiographic and anthropological studies revealed that 30% of the individuals were children, from the neonatal period to an age of about 10 years. Bone analysis showed that some of the subjects suffered from infectious diseases and certain metabolic disorders. The femur of one adult showed clear signs of amputation, which the person had to survive.

Une paire de sphinx colossaux découverts dans le Temple de Millions d'Années d'Amenhotep IIIA pair of colossal sphinx discovered in Amenhotep III Millions of Years temple

Photos: Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (MoTA)

Une mission germano-égyptienne dirigée par Hourig Sourouzian a mis au jour un ensemble de gros fragments en calcaire, dont certains appartiennent à une paire de sphinx royaux de 8 mètres de long environ, représentant le pharaon Amenhotep III portant le némès, la barbe royale et un large collier autour du cou. Ces fragments étaient à moitié immergés dans l'eau à l'arrière de la porte du troisième pylône et sont en mauvais état. Selon Sourouzian, il s'agit d'une importante découverte, car la présence de cette paire de sphinx colossaux atteste du début de la voie processionnelle menant du troisième pylône à la cour péristyle, où était célébrée chaque année la Belle Fête de la Vallée, ainsi que les fêtes jubilaires du roi. En effet, l'équipe a retrouvé des fragments en grès, avec un décor en relief représentant des scènes du Heb-sed, la fête jubilaire d'Amenhotep III, et des scènes d'offrandes à diverses divinités.

Aujourd'hui, tous les blocs et colosses découverts sont en cours de restauration pour tenter de les remettre à leur emplacement d'origine dans le temple.

A German-Egyptian mission directed by Hourig Sourouzian uncovered a collection of huge limestone pieces, some of them belonging to a pair of 8 metres long royal sphinxes of king Amenhotep III wearing the nemes headdress, the royal beard, and a broad collar around the neck. They were half submerged in water at the rear of the gateway of the third pylon. Both are in poor condition. Sourouzian said that the presence of this pair of colossal sphinxes attests to the beginning of the processional way leading from the third pylon to the Peristyle Court, where the beautiful 'Festival of the Valley' was celebrated each year, as well as the jubilee festivals of the king. In fact, pieces of sandstone wall decoration in the relief depicting scenes of the Heb-sed, the jubilee festival of Amenhotep III, and offering scenes to diverse deities, were also unearthed.

Now, all discovered blocks and colossi are under restoration in an attempt to re-erect them in their original location in the temple.

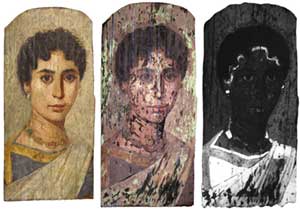

Les portraits du FayoumAt face value

Photos: APPEAR

studied using special filters.

Left to right visible-ultraviolet-infrared

to identify pigments and binding agents

Cet article porte sur les nouvelles méthodes d'investigation des portraits dits du Fayoum qui ornaient de nombreuses momies dans l'Égypte romaine. Plus de 1000 de ces portraits, peints sur des panneaux de bois ou des linceuls en tissu entre le premier et le troisième siècle de notre ère, se trouvent aujourd'hui dans les musées. À la fin du XIXe et au XXe siècle, les archéologues ont mis au jour des dizaines de ces portraits, principalement dans la région du Fayoum, en Basse-Égypte. Les excavateurs enlevaient souvent les panneaux ou les linceuls des momies, se débarrassaient des corps et vendaient les portraits à des institutions. Jusqu'à récemment, les archéologues ont concentré leurs efforts sur la recherche d'éléments stylistiques et l'établissement de l'identité et de l'appartenance ethnique des défunts, mais peu de chercheurs se sont penchés sur la manière dont les peintures étaient réalisées. Marie Svoboda, conservatrice au Paul Getty Museum, est l'une d'entre eux : "Je suis intéressée par la compréhension des portraits en termes de pratiques du travail dans l'antiquité"

. À ce jour, elle a fait appel à des collègues de 49 institutions internationales pour collaborer au projet APPEAR (Ancient Panel Paintings : Examination, Analysis, and Research). Jusqu'à présent, un tiers de tous les portraits connus de momies ont été étudiés en utilisant des méthodes non invasives. Pour la première fois, les scientifiques peuvent comparer les éléments visuels des peintures aux matériaux et techniques utilisés par les artistes pour les créer. Les chercheurs apprennent où les artistes se procuraient leurs matériaux, étudient comment les considérations économiques ont pu motiver les choix des mécènes et des peintres, et révèlent même des coups de pinceau cachés qui offrent un aperçu de la façon dont les artistes créaient leurs œuvres.

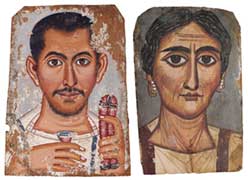

with pigment imported from southern Spain

Une fois qu'un support pour le portrait, en bois ou en tissu, a été choisi et préparé, les artistes ont utilisé différentes techniques et matériaux pour appliquer les pigments. Une technique était la détrempe, qui comprend un moyen de liaison à séchage rapide, comme la colle animale ou la gomme végétale. Une autre est l'encaustique, une méthode dans laquelle les artistes mélangent des pigments avec de la cire d'abeille fondue et utilisent des outils chauffés pour manipuler la peinture obtenue. La commande d'un portrait était l'apanage des riches à l'époque romaine, mais il y a riches et riches: la gamme des matériaux utilisés et les différences de qualité de la peinture reflètent ces différences socio-économique, même dans les rangs privilégiés de la société en Basse-Égypte.

Selon Svoboda : "Le plus probable est que ces portraits aient été peints au moment de la mort et qu'ils représentent un reflet de la vie de la personne."

Les spécialistes continuent de débattre de la fidélité du portrait, mais tous s'accordent à dire qu'elles présentent une façette du défunt : "Ils ne peuvent pas être n'importe qui, n'importe quel visage ou individu [...] Il doit y avoir quelque chose d'essentiel qu'ils communiquent sur une personne pour son voyage dans l'au-delà"

. Bien que les artistes aient peint leurs sujets avec certains traits faciaux individualisés, ils semblent avoir employé une gamme relativement limitée de conventions et de caractéristiques stylistiques. Il s'agit notamment de la représentation de personnes ayant une posture de face et de grands yeux proéminents. À bien des égards, les portraits sont des représentations idéalisées et les aspirations d'individus. ""En Égypte romaine, les gens construisaient leur iconographie mortuaire pour répondre à certains critères qui, dans la compréhension égyptienne de l'au-delà, étaient destinés à préserver le corps dans sa plus belle forme."

Ne manquez pas cette publication en accès libre : Marie Svoboda et Caroline R. Cartwright (eds.)

Portraits de momies de l'Égypte romaine : Recherches émergentes du projet APPEAR (2020). HERE

This article is about the new methods of investigation of the so-called Fayum portraits which adorned many mummies in Roman Egypt. More than 1,000 mummy portraits, painted on wood panels or cloth shrouds between the first and third centuries A.D., are in museums today. In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, archaeologists unearthed scores of these portraits, primarily at cemeteries in and around the Fayum region of Lower Egypt. Excavators often removed the panels or shrouds from the mummies, discarded the bodies, and sold the portraits to institutions. Until recently, archeologists have focused their efforts on researching stylistic elements and establishing the identities and ethnicities of the deceased, but few researchers have investigated how the paintings were made. Marie Svoboda, curator at the Paul Getty Museum is one of them: "I'm interested in understanding the portraits in terms of ancient working practices."

To date, she has enlisted colleagues from 49 international institutions to collaborate on a project called APPEAR (Ancient Panel Paintings: Examination, Analysis, and Research). Thus far, using non invasive methods, they have studied one-third of all known mummy portraits. For the first time, scientists can now compare visual elements of the paintings as well as the materials and techniques artists used to create them. Researchers are learning where artists obtained their materials, investigating how economic considerations might have motivated the choices of patrons and painters, and even revealing hidden brushstrokes that offer a glimpse of how artists created their work.

a pink floral wreath

and a glass of wine

Right side, older woman with

wrinkles and graying hair

Once a portrait canvas, either wood or cloth, was selected and prepared, artists used different techniques and materials to apply pigments. One technique was tempera, which includes a quick-drying binding medium such as animal glue or plant gum. Another was encaustic, a method in which artists mixed pigments with molten beeswax and used heated tools to manipulate the resulting paint. Even though commissioning a mummy portrait was largely the preserve of the wealthy in the Roman period, the range of materials used and the variety in the quality of painting reflect differences even within the privileged ranks of society in Lower Egypt.

Svoboda says: "Most likely, these portraits were painted at the time of death and represent a reflection of the person's life."

Although scholars continue to debate the extent to which the paintings are intended to be accurate portrayals, they agree that they present a version of the deceased. "They can't just be anybody, any face or individual [...] There has to be something essential that they communicate about a person for their journey to the afterlife"

. Although artists painted their subjects with some individualized facial features, they appear to have employed a relatively narrow range of stylistic conventions and characteristics in nearly all extant portraits. These include portraying people with a front-facing posture and large, prominent eyes. In many ways, the portraits represent idealized, aspirational depictions of individuals. ""In Roman Egypt, people constructed their mortuary iconography to meet certain criteria that, in the Egyptian understanding of the afterlife, were meant to preserve the body in its most beautiful form."

Don't miss this open access publication: Marie Svoboda and Caroline R. Cartwright (eds.)

Mummy Portraits of Roman Egypt: Emerging Research from the APPEAR Project (2020) HERE

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment