https://hyperallergic.com/428090/egyptian-art-anne-goodison-exhibition/

History

The Egyptian Artifacts of a Little-Known, Victorian-Era Woman Collector

An exhibition at the Atkinson Art Gallery and Library sheds light on the somewhat mysterious 19th-century scholar and collector Anne Goodison.

For Victorian women with access to education and funds, Egypt could serve as a source of adventure and even escape from a restricting society. Women such as Marianne Brocklehurst, Annie Barlow, and Amelia Edwards journeyed to the desert, often more than once, not simply as wide-eyed tourists but as dedicated collectors and scholars whose knowledge could rival that of some of their male peers. Their visits built their legacies: Barlow, for one, is recognized as the mother of the Bolton Museum's Egyptian collection; Edwards co-founded the Egyptian Exploration Fund, now known as the Egypt Exploration Society, to promote fieldwork in Egypt.

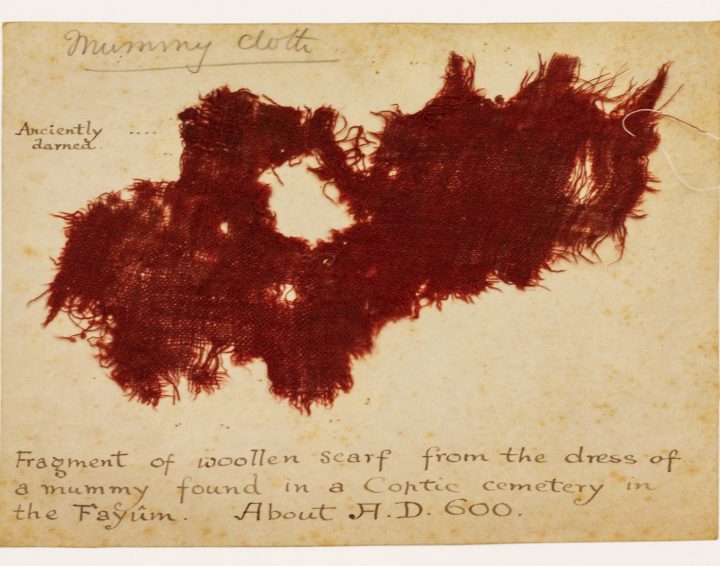

One other notable woman bitten by the Egyptology bug was Anne Goodison, whose collecting habits serve as a focal point for an exhibition at the Atkinson Art Gallery and Library in England. Goodison visited Egypt in 1887, when she was in her 40s, and then again in 1897. Over the course of her travels, she amassed nearly 1,000 objects in her collection — from jewelry to wooden coffin lids to ritual statuettes — which she kept private until her death in 1906. Adventures in Egypt – Mrs Goodison & Other Travellers presents her trove supplemented by loans from major museums including the British Museum and the Brooklyn Museum that place her within the broader, complicated history of collecting Egyptian objects under British imperialism.

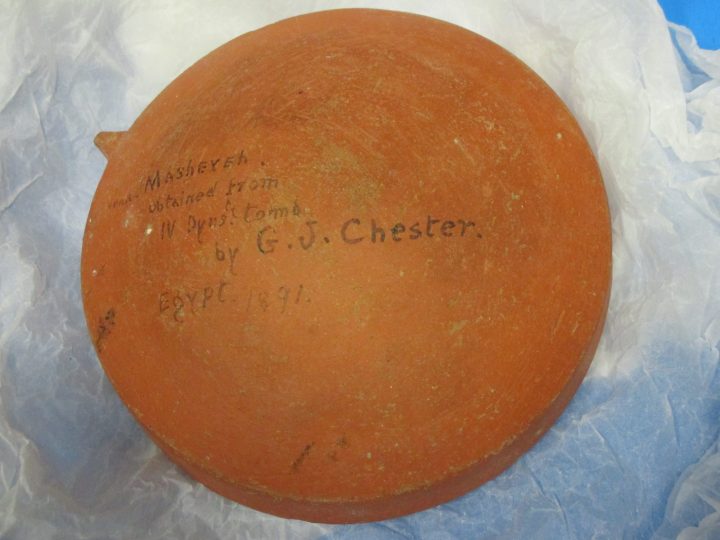

Born Anne Padley in 1845, Goodison married a civil engineer whose career allowed the pair to retire early in the Lake District. (Their neighbor, significantly, was the critic John Ruskin, who would often welcome them over to tea.) Very little is known about Anne Goodison: no diaries have surfaced, and no identifiable photographs or portraits of her have survived. What she did leave behind was her collection of Egyptian objects, which are often labelled by her handwritten notes. Her careful records speak to her strong desire to deepen her knowledge and appreciation of ancient Egyptian culture.

"She was more than just a lady who lunched and liked Egypt," curator and archaeologist Tom Hardwick told Hyperallergic. "She was campaigning for excavations, and she showed her druthers by learning hieroglyphs and corresponding with scholars.

"She was doing her own research at a time when women were barred by law and social pressure from having professional careers, in many cases," he continued. "She was trying very hard to earn and justify her credibility as someone with a serious interest in Egypt."

Egyptomania had long gripped Western Europeans by Goodison's lifetime, following Napoleon's failed military campaign that ended in 1801. It's uncertain what specifically sparked this Victorian individual's interest in Egypt, although Hardwick notes that she was certainly fascinated with the work of Edwards and her popular travelogue, A Thousand Miles Up the Nile. Trips to Egypt were also easily arranged then, thanks to the British travel agent Thomas Cook, who provided holiday packages that took British visitors from site to site. Relatively well-off, Goodison chose to hire her own dahabeya to travel under her own sail and move at her own speed.

By her first visit, British forces had occupied the country for nearly five years. The Atkinson's exhibition strives to showcase Goodison's collection in the context of this involved history of war, politics, and imperialists' powers. One section, for instance, explores how British influence over Egypt was administered under officials such as Lords Cromer and Kitchener.

About half of the objects on view represent Goodison's habits as a collector. Among them are letters sent between her and the Egyptologist Charles Edwin Wilbour, who helped her learn hieroglyphics. Yet, while her interests in the culture were serious, her reasons behind forming her collection were clearly very personal, Hardwick said. Many of the artifacts she acquired are simple ones, like small stone fragments and pot shards that she picked up while walking around ancient sites, like souvenirs. Others she purchased from dealers. On her second trip, she travelled with the clergyman Greville John Chester, who helped her make some of her acquisitions. (Chester, himself a collector of Egyptian artifacts, is known for acquiring what is now one of the oldest prosthetic devices.)

For the most part, Goodison didn't seek out highly unique objects, although the amulets, votive figures, and faïence ushabtiu are cherished today and do speak to the history of traveling and collecting in Egypt. She did collect three very special figurines known today as paddle dolls. Dating to about 2000 BCE, they are carved wooden slabs that represent stylized figures of women, and were produced during a fairly short period in ancient Egyptian culture.

"They are pretty rare," Hardwick said. "Most museums would be glad to have one, and Mrs. Goodison collected three. It's something that really shows that she was a discerning collector — she knew what she was acquiring."

In the late 19th-century, antiquities were supposed to be approved for export by a curator at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. After Goodison presumably completed the necessary paperwork, she brought all her objects back to England, where she kept them under her own guard instead of selling them or placing them in museums. Sadly, it seems that Mr. Goodison did not share her passions. While Anne might have found some level of liberation in her studies and adventures, her collection ultimately ended up in her husband's control. Two years after her death in 1906, he sold, rather than gifted, the entire trove to the local museum, evidently seeing in it pure financial value.

His deed, however, did mean that Anne's collection remained unified and was displayed to the public for many decades. In 1974, the museum closed, and the entire collection was transferred once more, to the Atkinson. It now stands as a rare example of a private collection from the 19th century that has not been broken up and dispersed. It also provides a voice to a long-forgotten woman who worked independently to participate and establish herself in a male-saturated field. Goodison's dedication is emphasized by the fact that many objects are labelled with numbers that indicate a catalog system of sorts, although no catalog survives. This system could have lent important insight into how she would have organized and displayed her prized possessions; its loss only adds further mystery to this ancient collector's story.

"Her controlling mind, her vision for the collection — even if we can't quite decipher it, it's still intact, hopefully to be deciphered at some point in the future," as Hardwick said.

Adventures in Egypt – Mrs Goodison & Other Travellers continues at the Atkinson Art Gallery and Library (Lord Street, Southport PR8 1DB, United Kingdom) through March 10.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment