http://www.dailysabah.com/arts-culture/2015/10/10/in-the-footsteps-of-a-pioneer-archaeologist

In the footsteps of a pioneer archaeologist

KAYA GENÇ

ISTANBUL

Published

October 9, 2015

Alan M. Greaves, the interim chair of the Department of Archaeology at the University of Liverpool, talked to Daily Sabah about his ANAMED exhibition: ‘John Garstang's Footsteps Across Anatolia'

Professor John Garstang, one of the leading figures of British

archaeology, has made an unexpected comeback in Turkey, the country that

left such a strong impression on him in the first decade of the 20th

century when he directed excavations in Anatolia. Istanbul's Research

Center for Anatolian Civilizations (ANAMED) kicked off the new season

with "John Garstang's Footsteps Across Anatolia," an exciting new

exhibition highlighting the British scientist's contributions to the

study of archaeology in Turkey.

Beautifully designed by the Tetrazon Museum and Exhibition Production team led by Burçak Madran, the ANAMED exhibition tracks Garstang's footsteps in Anatolia. Alan M. Greaves, a senior lecturer in archaeology at the University of Liverpool, who has been working on archaeology in Turkey for the past two decades, curated the show. Greaves, who specializes in the Bronze and Iron Ages of Anatolia, has done research and fieldwork at the sites of Oylum Höyük, Miletos and Aphrodisias.

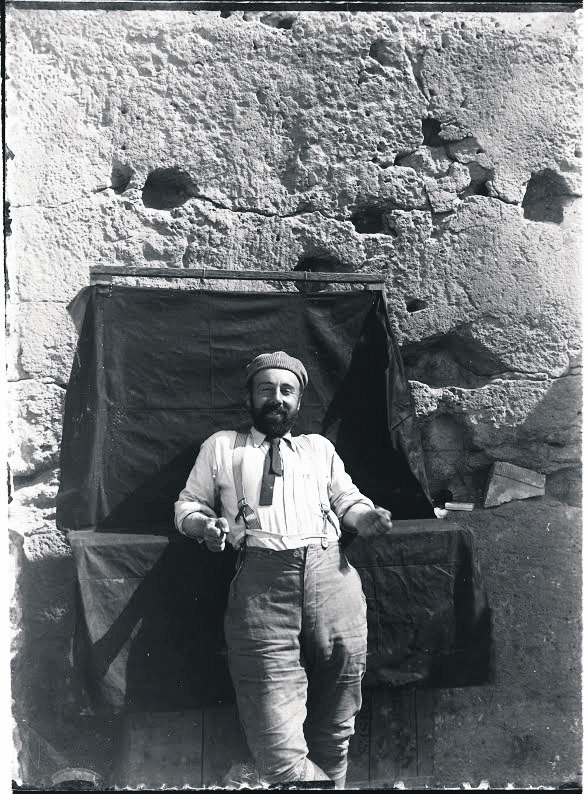

Greaves displays Garstang's photos of Anatolian people - Turks, Kurds, Greeks, Armenians, Christians and Muslims - taken during his journeys across Anatolia starting in 1907 until his death in 1956. Garstang's search for the remnants of the ancient Hittite Empire in Anatolia and northern Syria is well documented since he meticulously photographed every step of the excavations. Garstang used photography to precisely record his archaeological findings and was one of the earliest advocates of using the technique.

"I must admit that I had not heard of John Garstang until I came to work at the University of Liverpool in 1999," Greaves told Daily Sabah. His lack of acknowledge about the pioneering archaeologist was surprising given that Greaves had been working on archaeology in Turkey since the early 1990s. He was a partner in a Turkey-EU funded partnership with the Fethiye Museum and organized an international conference at the British Museum titled "Transanatolia: Connecting East and West in the Archaeology of Turkey." His monographs on archaeology in Turkey include "The Land of Ionia" and "Miletos: A History."

"This is a shame because Garstang really should be better known," Greaves said, adding: "There are really two things that single him out for me. Firstly, his career spanned the first half of the 20th century, which was a period of great change, spanning the transition from the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic. The second is his excellent photographic archive."

Garstang's photographic archive is crucial for Greaves and played a central role in his curatorial process for this exhibition. "Over five years, the University of Liverpool has systematically digitized and catalogued thousands of Garstang's glass plate photographic negatives to create a new archive of digital surrogates," the exhibition program says. "This is a primary research resource for archaeologists and anthropologists recording the lost monuments and lifestyles of Turkey and northern Syria in the late Ottoman period, with many of them seen here for the first time in over a century."

"Photography was not a new technology at the time, but it was the way in which Garstang used it that was so special," Greaves said. "The sheer number and quality of the images that he took means that we can recreate his excavations and travels in a way that is seldom possible for any other sites. He used photography as a form of shorthand recording to capture the artifacts and architecture as he found them in situ."

Garstang used the photographs to make an impression on his British sponsors. Seeing them was meant to reassure them that their investment was being spent in the right way.

"Garstang used his photographs to justify the investment that his sponsors back in Britain had made in his expeditions by showing them the marvelous things he had discovered," Greaves explained. "He also made sure that in some images he was dressed smartly in British clothes, drinking tea from an English teapot, and not a Turkish samovar, and using new British technology. However, in more candid snapshots he is seen laughing with his local workmen and sitting on the ground talking to them, presumably in Arabic or Turkish, both of which he spoke well."

Born in Blackburn in 1876, Garstang was educated at Jesus College, Oxford, where he studied mathematics before focusing on archaeology. He conducted excavations in Egypt, northern Syria, Nubia, Sudan, Palestine and Britain. In 1947 Garstang founded the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara (BIAA) and acted as its first director. He was a professor of archaeology at the University of Liverpool for about 35 years.

"As members of the public we often assume that archaeology is all about excavation, but what Garstang did in 1907 was to conduct a survey by traveling across Turkey noting and photographing Hittite monuments," Greaves noted. "This allowed him to prove that the Hittite Empire was much bigger than scholars had previously thought and laid the foundation for over a century of research in the field of Hittite geography."

Organized in collaboration with the University of Liverpool, the exhibition continues until Dec. 10 and features archival materials from the Gartsang Museum of Archaeology and the BIAA, which Greaves chose to exhibit thematically rather than chronologically.

"Even though I am an academic researcher, I thought it would be nice for visitors to explore the collection for themselves, be inspired by it and take away their own impressions of these amazing photographs!" Greaves said. "I wanted to share with them a bit of the on-going archival research process that we are engaged in and share the excitement that we ourselves feel every time we see a new image or read a new document. Giving members of the public a love of learning and an insight into what it is that archaeologists do is far more valuable than just a history lesson."

Beautifully designed by the Tetrazon Museum and Exhibition Production team led by Burçak Madran, the ANAMED exhibition tracks Garstang's footsteps in Anatolia. Alan M. Greaves, a senior lecturer in archaeology at the University of Liverpool, who has been working on archaeology in Turkey for the past two decades, curated the show. Greaves, who specializes in the Bronze and Iron Ages of Anatolia, has done research and fieldwork at the sites of Oylum Höyük, Miletos and Aphrodisias.

Greaves displays Garstang's photos of Anatolian people - Turks, Kurds, Greeks, Armenians, Christians and Muslims - taken during his journeys across Anatolia starting in 1907 until his death in 1956. Garstang's search for the remnants of the ancient Hittite Empire in Anatolia and northern Syria is well documented since he meticulously photographed every step of the excavations. Garstang used photography to precisely record his archaeological findings and was one of the earliest advocates of using the technique.

"I must admit that I had not heard of John Garstang until I came to work at the University of Liverpool in 1999," Greaves told Daily Sabah. His lack of acknowledge about the pioneering archaeologist was surprising given that Greaves had been working on archaeology in Turkey since the early 1990s. He was a partner in a Turkey-EU funded partnership with the Fethiye Museum and organized an international conference at the British Museum titled "Transanatolia: Connecting East and West in the Archaeology of Turkey." His monographs on archaeology in Turkey include "The Land of Ionia" and "Miletos: A History."

"This is a shame because Garstang really should be better known," Greaves said, adding: "There are really two things that single him out for me. Firstly, his career spanned the first half of the 20th century, which was a period of great change, spanning the transition from the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic. The second is his excellent photographic archive."

Garstang's photographic archive is crucial for Greaves and played a central role in his curatorial process for this exhibition. "Over five years, the University of Liverpool has systematically digitized and catalogued thousands of Garstang's glass plate photographic negatives to create a new archive of digital surrogates," the exhibition program says. "This is a primary research resource for archaeologists and anthropologists recording the lost monuments and lifestyles of Turkey and northern Syria in the late Ottoman period, with many of them seen here for the first time in over a century."

"Photography was not a new technology at the time, but it was the way in which Garstang used it that was so special," Greaves said. "The sheer number and quality of the images that he took means that we can recreate his excavations and travels in a way that is seldom possible for any other sites. He used photography as a form of shorthand recording to capture the artifacts and architecture as he found them in situ."

Garstang used the photographs to make an impression on his British sponsors. Seeing them was meant to reassure them that their investment was being spent in the right way.

"Garstang used his photographs to justify the investment that his sponsors back in Britain had made in his expeditions by showing them the marvelous things he had discovered," Greaves explained. "He also made sure that in some images he was dressed smartly in British clothes, drinking tea from an English teapot, and not a Turkish samovar, and using new British technology. However, in more candid snapshots he is seen laughing with his local workmen and sitting on the ground talking to them, presumably in Arabic or Turkish, both of which he spoke well."

Born in Blackburn in 1876, Garstang was educated at Jesus College, Oxford, where he studied mathematics before focusing on archaeology. He conducted excavations in Egypt, northern Syria, Nubia, Sudan, Palestine and Britain. In 1947 Garstang founded the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara (BIAA) and acted as its first director. He was a professor of archaeology at the University of Liverpool for about 35 years.

"As members of the public we often assume that archaeology is all about excavation, but what Garstang did in 1907 was to conduct a survey by traveling across Turkey noting and photographing Hittite monuments," Greaves noted. "This allowed him to prove that the Hittite Empire was much bigger than scholars had previously thought and laid the foundation for over a century of research in the field of Hittite geography."

Organized in collaboration with the University of Liverpool, the exhibition continues until Dec. 10 and features archival materials from the Gartsang Museum of Archaeology and the BIAA, which Greaves chose to exhibit thematically rather than chronologically.

"Even though I am an academic researcher, I thought it would be nice for visitors to explore the collection for themselves, be inspired by it and take away their own impressions of these amazing photographs!" Greaves said. "I wanted to share with them a bit of the on-going archival research process that we are engaged in and share the excitement that we ourselves feel every time we see a new image or read a new document. Giving members of the public a love of learning and an insight into what it is that archaeologists do is far more valuable than just a history lesson."

No comments:

Post a Comment