https://hyperallergic.com/526963/john-beasley-greene-sfmoma/

Photography's Potential as Art and Science in Documenting Ancient Egypt

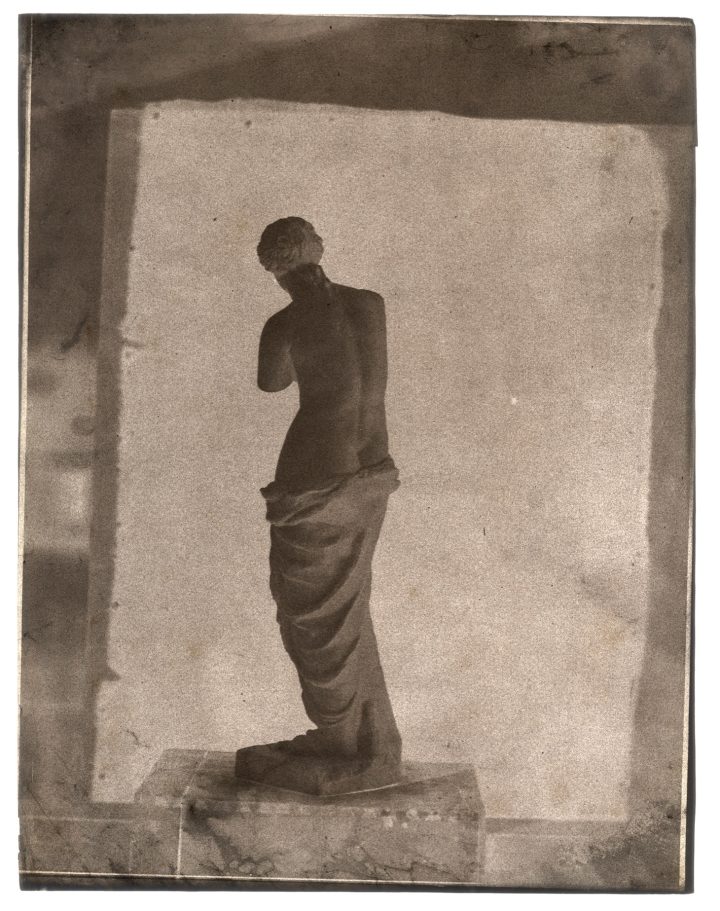

Signs and Wonders: The Photographs of John Beasley Greene features photographs that focus on ancient monuments and landscapes in Egypt and Algeria from the 1850s, rather than people.

SAN FRANCISCO — Ancient Egypt has turned up in some unexpected museum exhibitions this year. First, there was the Pulitzer Arts Foundation's Striking Power: Iconoclasm in Ancient Egypt, followed by the Freud Museum London's exhibition on Freud's fascination with Egypt. Now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art has opened Signs and Wonders: The Photographs of John Beasley Greene, featuring photographs of ancient monuments and landscapes in Egypt and Algeria from the 1850s.

John Beasley Greene is an enigmatic figure. Almost nothing was known of his life until about 40 years ago, and even after four decades of research biographical details are sparse. We do know that he came from a wealthy American banking family resident in France. Like many other photographers of the day (including fellow pioneering photographer of Egypt Maxime Du Camp, and Auguste Salzmann, whose Palestine photographs were the subject of a recent Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition), Greene trained under the influential Gustave Le Gray. What set Greene apart was his dual role as photographer and archaeologist. As the exhibition notes, he was the first known archaeologist to photograph Egypt. Greene took at least two trips to Egypt (between 1853 and 1855), the first for travel and photography, the second largely for excavation. On these visits he photographed not only ancient monuments but also excavations in progress — his own at the site of Medinet Habu as well as those of Frenchman (and future founding director of Egypt's Antiquities Service) Auguste Mariette at Giza. He then traveled to Algeria from 1855 to 1856 for more archaeological and photographic projects. But Greene died shortly after his return, only 24 years old.

Greene's photographs, frequently exhibited during his lifetime, were forgotten quickly soon after, until revived about 40 years ago. Since that time, many of Greene's prints have come on the art market and so are more widely available today. The current exhibition — the first to focus exclusively on Greene — features a large number of Greene's prints (86 total) from a wide range of museums and private collections, including the SFMOMA's own holdings.

That recent transition from a long period of obscurity to renewed interest also characterizes the 1840s photographs of Frenchman Girault de Prangey, the subject of the Met's exhibition Monumental Journey from earlier this year. Like Girault, Greene was able to take advantage of his independent wealth and France's status as a colonial power to study photography and to travel around the Mediterranean using it. But their techniques were quite different. Girault, active near the beginnings of photography, worked with daguerreotypes — his images are sharp and remarkably detailed even in miniature format. By contrast, Greene adopted his teacher Le Gray's innovative technique for making waxed paper negatives and salted paper prints. The coarse nature of the paper surface lent his images a softer, more atmospheric quality — one that for Greene, like Le Gray, became an aesthetic preference. The difference is clearly visible in the images on display.

In addition to the prints, there are four paper negatives on one wall, with a button beneath each (press it and you can illuminate the negative to see it better). The curator, Corey Keller, explained in an email that she chose to display these in part because many viewers, in this digital age, may never have seen a photographic negative before. However, even many older viewers (like me), have never seen 19th-century paper negatives. While the small size of Girault's daguerreotypes stood out in Monumental Journey, here I was struck by how large the negatives are, in comparison with 35 mm film negatives.

Greene's application of photography to archaeology resulted in a combination of the two strands of interest in early photography (as the exhibition does well to note): photography as art and photography as science. Of course, this combination was not new. W.H.F. Talbot, one of the inventors of photography in the 1830s, was also a respected Assyriologist, though he kept these pursuits separate. But the same combination of scientific and aesthetic concerns seen in Greene is already visible with Girault de Prangey, who had taken the earliest surviving photographs of Egypt and West Asia a decade earlier. Nor was Greene the first person to photograph an archaeological excavation in progress. (In the catalogue, Keller suggests it was Gabriel Tranchard at Victor Place's Khorsabad excavations in 1852.) But he was, as far as we know, the first to photograph an excavation in progress in Egypt — Auguste Mariette's excavations by the Sphinx at Giza, in 1853-54. He was also the first practicing archaeologist to photograph the country. This is significant, because it meant he was attuned to specific needs and problems that other photographers (like Girault or Du Camp) were not. Greene was very concerned with recording inscriptions of significance to Egyptology, but this was made difficult by the lighting, as building walls with inscriptions were often split between bright sunlight and shadow. Greene's innovative solution was to make casts of the inscriptions and then photograph the casts.

Why is this? Is it due to lengthy exposures, or something else? Keller explained to me that Greene left little technical information on his photographic work, but we know from the manual that Gustave Le Gray published on his process that exposure times might have ranged anywhere from 30 seconds to 20 minutes, depending on the lighting conditions, the type of camera and lens, and what was being photographed. Capturing people in action could not be done except as a blur, but certainly posed images were possible. And yet we have few examples even of these. Keller points out in the catalogue that there are several negatives of people from Greene's Egyptian trips, but he never printed most of these. Of course, there was a risk of blurred images even with people standing or sitting still. And in fact, blurred figures can be made out in a few of his images.

Among the prints that are on display, Greene's focus is perhaps best summed up by a photograph of a shack next to a palm tree. Inside the shack we see one of the rare examples of a blurred person in a Greene print. But Greene chose to title this print as one of his "Studies of Date Palms" — as if the person and their domicile were invisible, or incidental.

Greene's photographs of Egypt and Algeria look much like typical European ones of the Orient in this period with their lack of people and focus on monuments and landscapes. (Discussed only at brief points in the exhibition, Greene's treatment of people and landscapes is explored in admirable depth in the catalogue.) But is this simply orientalism in Greene's case? We must be careful here. In his early photographs taken in France, too, Greene avoided images of people, and when he did take photographs of them he again failed to make prints. Yet, whatever the case, Greene's Egyptian images show the same stillness of the landscape we commonly see in photographs of the eastern Mediterranean at this time. "How much have things changed?" we might ask. Looking at Greene's photographs, we get the same effect as looking at almost any of the many exhibitions on ancient Egypt — modern Egyptians are conspicuously absent. The message, however dubious, is consistent: modern Egyptians have little connection to the past of their own country, a past which is instead at home among us in Europe and North America.

Where we do find the missing people is in the exhibition Hannah Collins: I Will Make Up a Song, which is mounted immediately beside Signs and Wonders in the museum. Collins's exhibition features a video installation on the work of Hassan Fathy, a prominent Egyptian architect of the 20th century. Fathy may be best known for planning new towns for the Egyptian poor. Two of those are featured here: New Baris and New Gourna.

New Gourna in particular is famous, or notorious (depending on your viewpoint) as part of the Egyptian government's decades-long efforts to remove the village of Gourna because it sat on part of the ancient Egyptian city of Thebes. (The government wished to preserve the ancient site and develop it for tourism. Besides standing in the way, the villagers had long conducted illegal excavations at the site.) One of Greene's prints on display in Signs and Wonders is of a temple at Gourna (also written Qurna), though the connection is not made in the exhibition.

Collins's video is essentially a slideshow of her photographs of New Gourna and New Baris — along with one slide of text, in both English and Arabic, repeated a couple of times — set to an eerie soundtrack. Her wall text at the entrance to the exhibition is ambivalent, suggesting Fathy's noble intentions in wanting to help the poor villagers while also showing sympathy for the residents in their attachment to their original villages. My impression of the film was different. That one slide of text, from which the title of the film is taken, is in the voice of the villagers, and centers on their desire not to be forcibly removed. "I will build my own place to live and I will not be driven from my home," as part of it reads. But Fathy's viewpoint is not present in the film, at least not directly.

I found I Will Make Up a Song moving at times, but in the end difficult to follow since the video is just a series of images without a clear story. Perhaps this is the point. But combined with Signs and Wonders, it has the potential to be a powerful meditation on the collision of the past and the present in Egypt, and the role of Egyptians themselves in this process. Closer integration of the exhibitions, and some more explicit discussion, might help visitors make those connections.

Signs and Wonders: The Photographs of John Beasley Greene and Hannah Collins: I Will Make Up a Song runs through January 5, 2020 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (151 Third Street, San Francisco, California). The exhibitions were curated by Corey Keller, curator of photography at SFMOMA. Signs and Wonders is scheduled to travel to the Art Institute of Chicago in February 2020.

Editor's Note: The author's travel expenses to San Francisco to see the exhibition were paid by SFMOMA.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment