An Egyptian Archaeological Treasure

Worker journals detail the scientific approach promulgated by George Reisner.

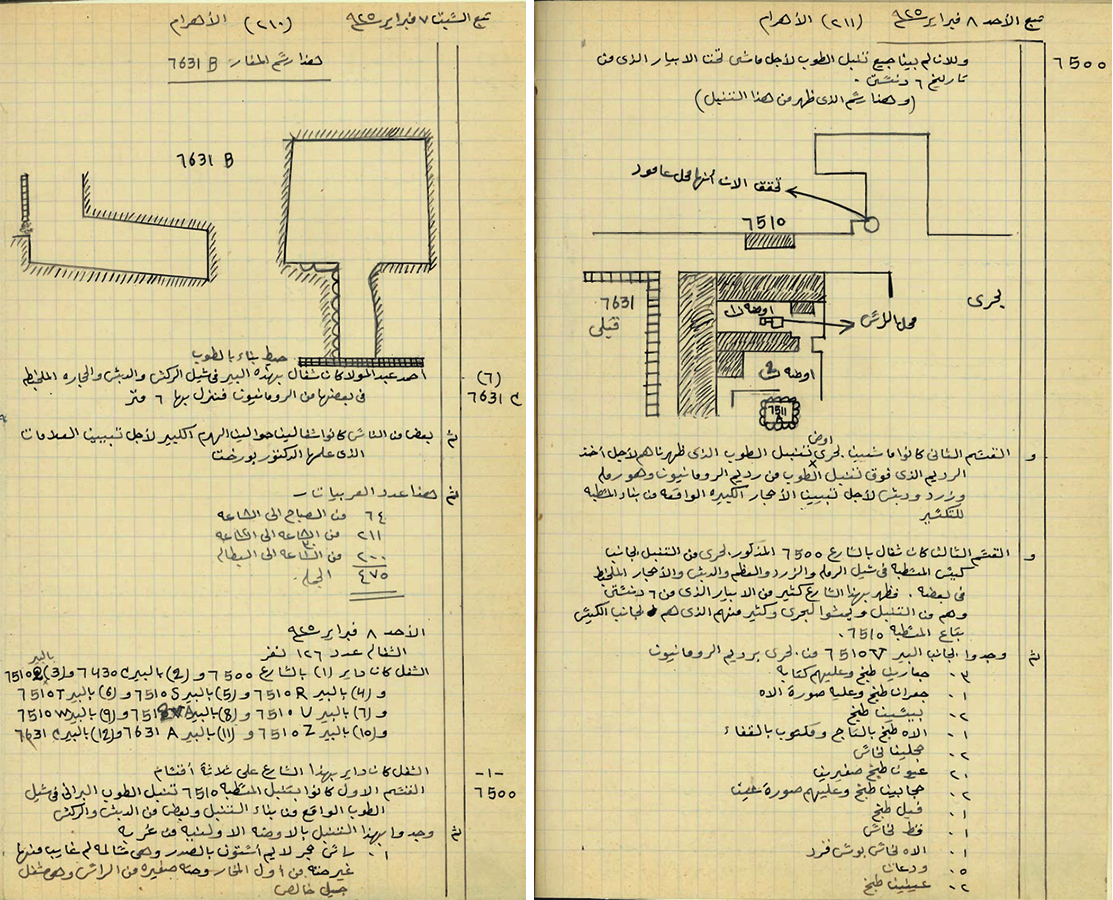

A page from the recovered diary of an Egyptian foreman trained by Harvard archaeologist George Reisner | COURTESY OF PETER DER MANUELIAN

While ample English-language records remain from such expeditions, Bell professor of Egyptology Peter der Manuelian—a director of the project to digitize, transcribe, and study the diaries—said that few other records exist written from the perspective of the Egyptian foremen so vital to that work. The digs of that era added scores of treasures to the holdings of prominent museums including the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the Metropolitan Museum of Art—both now renowned for their ancient Egyptian collections.

Now, historians, archaeologists, linguists, and other scholars can take a closer look at the role and observations of the highly trained locals who partnered with professionals to painstakingly record the progress, methods, and findings of their excavations. Though many expeditions were marked by outright looting and malpractice, the authors of these diaries had been trained by the legendary archaeologist George Reisner—the leader of a joint Harvard-MFA expedition, in part remembered for pioneering ethical standards of archaeology.

Preserving this unique record falls to Manuelian, as the heir to Reisner at Harvard, where Semitic studies, as they were then known, went seven decades without an Egyptologist after Reisner's death in 1942. Using twenty-first-century tools of archaeology to update Reisner's work—from digital teaching models to AI transcription—and bringing renewed attention to his remarkable career, which included leading the Harvard expedition to the Pyramids of Giza for decades, Manuelian is doing his best to close that 70-year gap by exploring and expanding his predecessor's legacy.

Through the early 1900s, when Egypt was under British control, Western expeditions to Giza abounded, Manuelian explained in an interview. Institutions of art and academia across the U.S. were restless to get in on the discoveries—and the plunder. The Met and the University of Pennsylvania had their own expeditions to Egypt, along with a string from France, Britain, and Germany. Many were marked by a lack of respect for the objects, with few records kept of the process of discovery or the objects' original state. For its part, Harvard enlisted Reisner, an Assyriologist and member of the class of 1889, to lead its expedition. He stood apart, says Manuelian: instead of simply working to enrich the MFA and Harvard, Reisner led a team of well-trained local foremen who carefully photographed and documented their work and findings, demonstrating a responsible and scientific archaeology that would go on to set the standard for the field.

Reisner devised critical methods of recording work performed by the expedition, including numbering systems, before-and-after photography, register books, and written journals.

After the re-discovery of the foremen's journals in the early 2000s, Manuelian raised funds to purchase them and is now working with his team to transcribe the handwritten Arabic, relying on a French machine-learning company to digitize them before then verifying, translating, and analyzing them—all while keeping the family originally in possession of them informed of the progress. More than a mere historical record of a major expedition, the diaries of Reisner's foremen, who were largely from the nearby Egyptian town of Quft, have helped show Manuelian—also a recent biographer of Reisner—the scale of his forerunner's exceptional practices. They're also precious sources of information on Egyptian Arabic from the time, labor relations, the origins of objects already established in museums, and even old handwriting.

"Reisner was ahead of his time by using a skilled labor force," Manuelian said. The time he took to teach them archaeological skills made them "indispensable," and in some local families—like the one whose diaries he is currently studying—several generations worked in partnership with Reisner during the expedition. Manuelian called it "absolutely unique."

"No other expedition was doing this," he continues. Many of his foremen went on to use their training in Iraq, Syria, Sudan, and other expeditions in Egypt, further increasing Reisner's influence and positive impact on the field.

The knowledge acquired as ancient objects were excavated helped advance Egyptology and Nubian studies (the latter of which hardly existed as a field at the time). For instance, the expedition was able to work out the chronology of Old Kingdom Egypt (which was the era of the pyramids) and of the Nubian empires, while providing more context surrounding the creation of the pyramids.

Manuelian has extended Reisner's influence into the present by developing virtual reality experiences at the Harvard Museums of the Ancient Near East (formerly the Semitic Museum), and sophisticated 3-D scanning of archaeological sites. He's built detailed digital models of past expeditions online and is using AI to transcribe century-old writings. He now has a small fleet of Ph.D. students under his wing, and is overseeing new classes in Egyptian hieroglyphics and GIS, plus a General Education course in archaeology. In short, the Egyptology program at Harvard is burgeoning again.

"It's just nice to see the baton get passed along," he said, as Harvard adopts "twenty-first-century approaches to [Egyptian] archaeology."

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment