Have a look at this video. https://www.today.com/video/-lost-city-in-egypt-discovered-by-archaeologists-109913669874

Inside Egypt's 3,000-year-old 'lost golden city'

A "lost golden city" in Egypt dating back 3,400 years has been revealed in what is being called the most important discovery in the country since the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1922.

The city, buried under sands near the modern-day city of Luxor for three millennia, was uncovered in September 2020 by a team led by Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass and was revealed to the world Thursday.

"This is amazing because actually we know a lot about tombs and afterlife," said Hawass while giving NBC News a tour of the site. "But now we discover a large city to tell us for the first time about the life of the people during the Golden Age."

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

2500

2500"Each piece of sand can tell us the lives of the people, how the people lived at the time, how the people lived in the time of the golden age, when Egypt ruled the world," he said.

"We spent a lot of time talking about mummies and talking about how they died, the ritual of their deaths. And this is the ritual of their lives."

The city is the largest uncovered from ancient Egypt and is only partly excavated. Artifacts including rings, scarabs and colored pottery confirmed the dating to the reign of Amenhotep III, who ruled Egypt from 1391 to 1353 B.C.

Hawass' team was searching for Tutankhamen's Mortuary Temple and was surprised to instead find a series of mud walls rising out of the sand, some about 10 feet tall and built in a zig-zag design characteristic of the period. Other archaeologists had previously searched for and failed to find the city.

With its storage houses, grinding stones, ovens and areas for meat production and everyday tools still intact, the site gives a rare glimpse into a working Egyptian city.

"The discovery of this lost city is the second most important archeological discovery since the tomb of Tutankhamen," Betsy Brian, a professor of Egyptology at Johns Hopkins University, said in the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities' news release.

Curiously, the team uncovered a buried skeleton lying with arms outstretched to his side and the remains of a rope around his knees. The ministry's statement described this as "odd" and said it would be investigated.

18731873187318731873

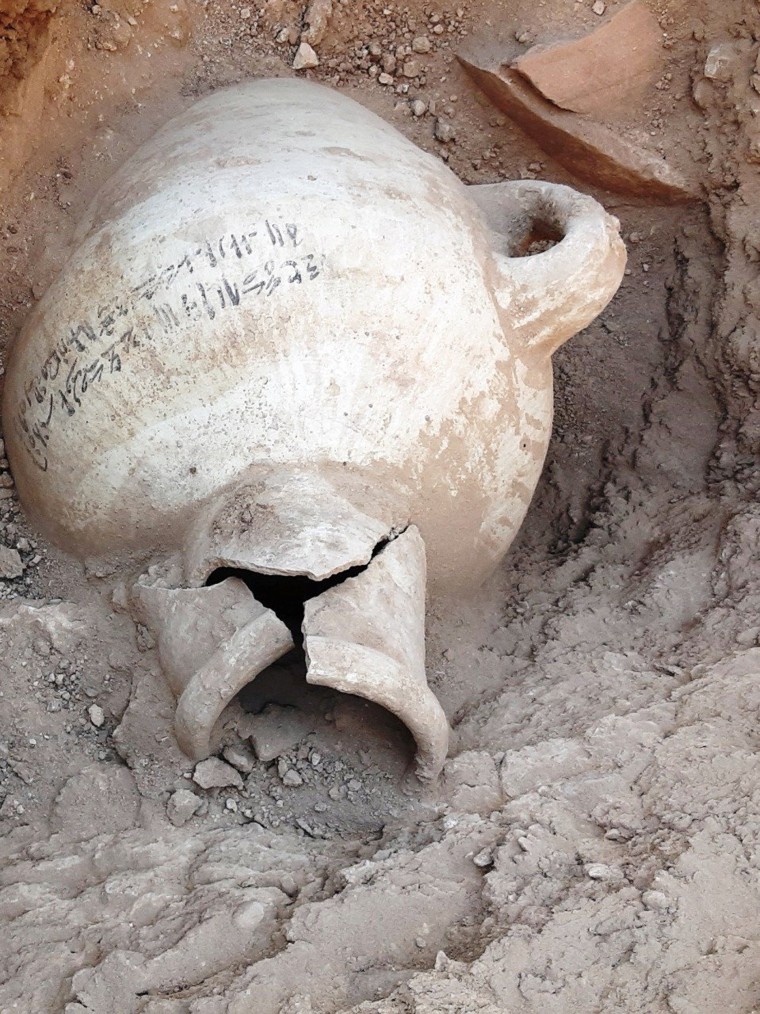

18731873187318731873A vessel, containing about 22 pounds of boiled or dried meat, came with an inscription. "That Year 37, dressed meat for the third Heb Sed festival from the slaughterhouse of the stockyard of Kha made by the butcher luwy."

The Egyptian team said this statement, which names two people who lived and worked in the city, also confirms that the city was active during Amenhotep III's reign alongside his son Akhenaten, who was succeeded by Tutankhamen.

Future excavations on a cemetery and unopened tombs at the site may help to answer even more questions about the period.

Hannah Pethen, a British archaeologist and honorary fellow of the University of Liverpool, who has worked on excavations in Egypt but wasn't involved in the Luxor dig, said the discovery was a landmark in the understanding of the region.

"Everybody loves the thought of an exciting, untouched tomb, but actually this is probably more significant and more important than if it was a pharaoh's tomb," she said.

"We have a lot of tombs and we know a lot about them, but we don't have a lot of evidence about how Egyptians lived and worked in their cities."

The newly discovered city is now one of three sites from around the same period — Rameses III's temple at Medinet Habu and Amenhotep III's temple at Memnon — and the newly discovered city's key role may be in confirming that things found there were common across the empire.

"This is really the major settlement on the west bank of the Nile from this period, so it's going to be directly associated with the tombs and cemeteries there, so we're adding to our understanding of that landscape. We have tombs, temples and now we have quite a big city," Pethen said.

One of the biggest mysteries of the period is why Akhenaten and his queen, Nefertiti, abandoned their religion and kingdom in Thebes (modern-day Luxor) to build a new city, where they worshipped the sun. Some hope the lost city will provide clues, but not everyone is optimistic.

"I wouldn't put any money on it. Ahkenaten has a habit of keeping his secrets — we've had several opportunities over the last 150 years to learn more, but somehow it's never quite come off, " Pethen said.

But as Hawass put it, our understanding of the ancient world is changing all the time: "You never know what the sand of Egypt might hide."

Charlene Gubash and Molly Hunter contributed reporting from Luxor, Egypt.

No comments:

Post a Comment