-- Sent from my Linux system.

The summer of 2020 gave us the occasion to observe a phenomenon as old as the hills and yet more witnessed than ever in the current climate: the destruction of images. At the heart of the events linked to the Black Lives Matter movement, many statues around the world have been the target of polemics and physical attacks.

Kneeling statue of Hatshepsut found buried in a pit in front of her temple (in the so-called 'Senenmut Quarry'), after being smashed into pieces under the reign of Thutmosis III. New York, MMA 29.3.1. Granite. H. 261; W. 80; D. 137 cm. Systematic targets on Hatshepsut's statues are the uraeus, nose and beard, as well as the wrists. The statues are also usually beheaded. Attacks on the eyes, visible on this statue, are less frequent. (Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, MMA excavations, 1927–28, Rogers Fund.)

Altering three-dimensional images that stood in squares, courtyards or public gardens was tantamount to punishing the characters depicted, now considered dishonorable because they have become symbols of slavery, colonialism or racism. Treated just like actual human bodies, these effigies have been disfigured, decapitated, mutilated. Even in contemporary societies, where it is generally accepted that no soul or spirit inhabits a body of stone or bronze, monuments and sculptures are not seen as mere ornaments. They have a role, they represent ideas, whether similar to those originally intended or not.

Pharaonic history provides us with well-documented cases of condemnation of the memory of specific individuals – what we today call damnatio memoriae, a Latin term created in the 17th century to label Roman memory sanctions. For example, the female pharaoh Hatshepsut, considered a usurper after her death, was erased from the official memory and removed from all her monuments. A few generations later, Akhenaten's figure was also eradicated from the monumental landscape, following the failure of his Atonist revolution. However, in the large panorama of Egyptian art, many other causes than the erasure of someone's memory led to the destruction or mutilation of images, and one should not be too quick to conclude on the motivations that may have led to their alteration.

When considering an altered monument, one should first address the following three questions:

– Is the mutilation intentional? How can this be ascertained?

– Is there any evidence allowing to date the mutilation? A few hours as well as several centuries or millennia can separate the installation of an image from its end.

– What sources are available to interpret this alteration?

When getting to this third question – the most difficult – three points should be considered:

– Who was the figure or entity represented? How was he/she perceived over time and how can we trace the evolution of this consideration?

– When and why was this image produced and/or installed?

– What were the motivations of those who harmed it?

When dealing with ancient and sometimes poorly documented monuments, it is difficult to answer the questions we have asked, but we must keep in mind that such a multiplicity of points of view is always a possibility. The perception of an image by its deteriorators may have been very different from the perception of the people who produced it, as well as that of the people who have been in contact with it over the centuries.

This kind of practice can be observed throughout Pharaonic history. Even more than in our modern societies, images were endowed with a strong "agency." They were performative, served as potential bodies in which the entity represented could take place, and they were therefore capable of action. An acting image could bring benefits – for example, it could serve as an intermediary between a worshipper and the figure represented, whether it was an ancestor, a deity or the reigning king – who was himself of divine essence. An image could also carry danger. For this reason, to avoid any risk that this image would take action, it was advisable to deactivate it by depriving it of its organs of life, its limbs or its inscriptions that conferred it an identity. A mutilated bas-relief or statue deprived of its arms and legs, its nose or even its face would go back to its first nature as a block of stone.

Mutilation or destruction of an image could serve many purposes. For example, the intention may have been to remove from view what one no longer wanted to see. The very performance of the destruction may also have been the goal of the act, whether it was performed in front of an audience or in the framework of some kind of ritual. This act of destruction was itself a producer of images, even if mental ones. Sometimes, too, the intention may have been to ostensibly leave visible the injuries brought to a figure.

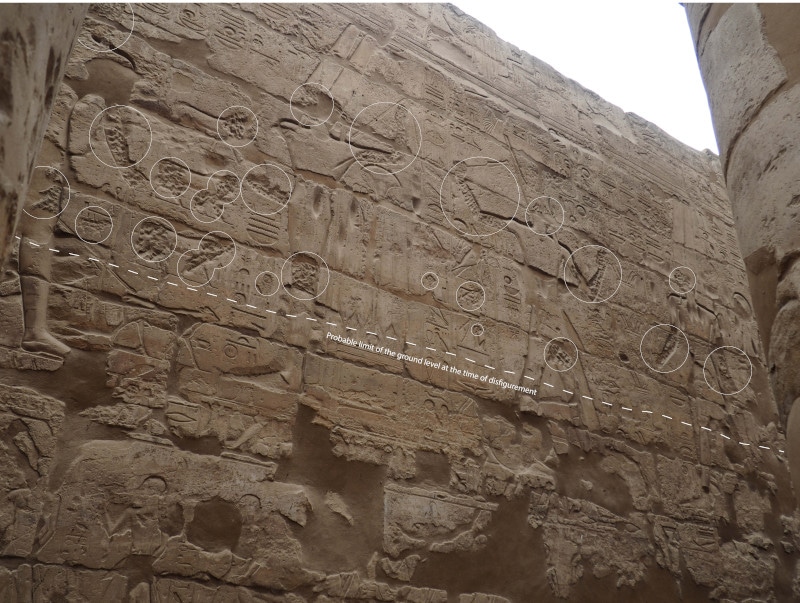

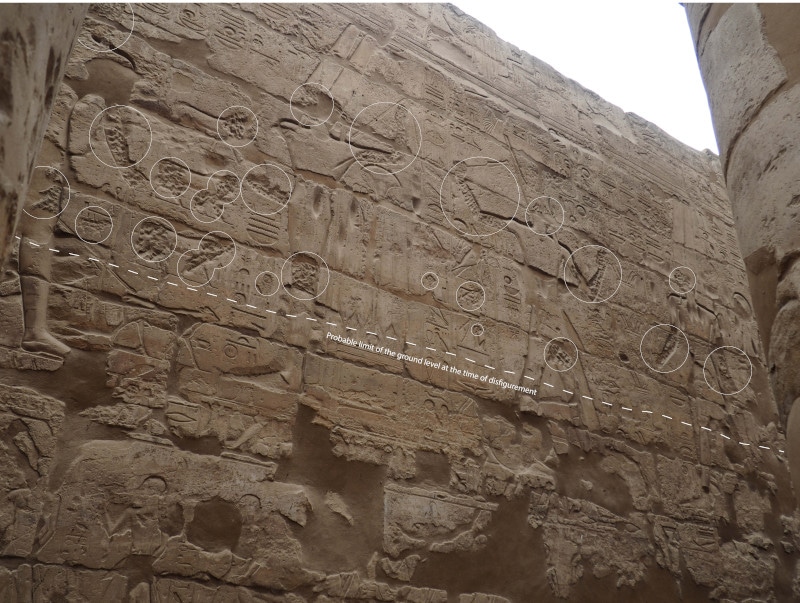

Let us mention the well-known case of Hatshepsut. The many statues from her temple at Deir el-Bahari were found mutilated at specific points (always the nose, beard, and uraeus; sometimes the eyes, the entire face, or limbs) before being broken into several pieces and buried in two pits in front of the temple. These statues did not remain visible for long in their mutilated form. We will never know if their destruction took place in front of an audience – we may assume so – but their destruction certainly followed a very systematic procedure. We know enough about the political context that led to the proscription of the female pharaoh's memory to be able to date the event to the end of the reign of Thutmosis III.

The case of Akhenaten is also well documented. At the end of Dynasty 18, with the seizure of power by Horemheb, a campaign of proscription seems to have taken place against the rulers attached to the memory of the Amarna revolution: Akhenaten and Nefertiti, their successor Neferneferuaten, Tutankhamun and Ay. When exactly did this proscription take place, how long did it last, how systematic was it? The rock-cut statues of the boundary stelae of Amarna remained clearly visible in their mutilated, outrageous form, as if to serve as a warning to those who, like Akhenaten, would fail in the mission entrusted by the gods. The countless statues of the royal family in Amarna and Thebes were all mutilated, often reduced into pieces and buried. The blocks covered with reliefs were reused as filling in the masonry of new temples.

The case of Akhenaten's son Tutankhamun, however, is more difficult to interpret. Horemheb, despite his relatively advanced age, adopted for his official representations a physiognomy very close to that of Tutankhamun (and Ay). This similarity allowed him to appropriate statues of both Tutankhamun and Ay; scholars are often uncertain whether a statue inscribed for Horemheb was adapted from one of his predecessors or was newly made for him. This adaptation of ancient representations is widely attested, both on the walls of temples and on statuary monuments.

But did Tutankhamun endure a proper campaign of destruction of his monuments accompanying his memory's condemnation, like his father? It was convenient to reuse the effigies of the boy king: a modification of the inscription was enough to transform them into representations of Horemheb. Some statues bearing the name of Tutankhamun, for example, were discovered in the "Karnak Cachette," a kind of sacred cache containing hundreds of statues dug in the courtyard behind the 7th pylon of the Amun temple in Karnak, during the 1st century BCE, that is to say 1200 years after the reign of Tutankhamun. Among them was a standing figure of the god Amen, on which Tutankhamen's cartouches have not been altered.

All Tutankhamun's surviving statues are more or less defaced, but many other motivations may also have been at work. The Louvre statues which show the seated god Amun bestowing his blessings on a small standing figure of Tutankhamun, although apparently intentionally damaged, might not have resulted from a personal attack against the king. The mutilations were not only directed against the pharaoh's figure, but also against the god's: in both cases, Amun too was beheaded and his forearms were broken, an act which would have made no sense in the time of Horemheb when the cult of Amun underwent a brilliant renewal. Our absence of knowledge regarding these statues' archaeological contexts found deprives us of information on the possible date of their abandonment.

Are there traces of iconoclasism dating to the installation of Christianity in Egypt? Several contexts suggest the destruction of pagan images around the 4th-5th centuries CE. Nevertheless, caution is required since many other contexts show a certain respect for – or simple disinterest in – ancient monuments. Wars, superstitious practices, ancient and modern looting, or the reuse of a statue or block as materials for example for building, among others, are possible causes of damage to Pharaonic period images. Any single monument may also bear the traces of different practices from varying periods. Finally, we must not neglect the destruction wrought by time and natural elements.

Statues were powerful, potentially dangerous, but also vulnerable vessels of sacral energy, and still have the power to be at the center of polemics. Activating, re-activating, transporting, retouching, transforming, mutilating, deactivating and concealing a statue appear to have been quite common manipulations throughout Egyptian history. In some cases, such attitudes have even continued, with renewed roles, during the post-pharaonic periods, which shows that they had continuing impact on people.

Statues were considered partners in social relationships and thus were endowed with agency. That agency did not only apply to the eyes of the inhabitants of the Nile Valley through all periods, but also in other cultures where Egyptian artifacts are found in large numbers, in the Sudan, in the Near East, in the Hellenistic and Roman worlds, as well as in Modern cultures. It is a wide field of research, which allows us to even reflect on our own interactions with the images that surround us.

Simon Connor is Chargé de Recherches (F.R.S.-FNRS) au Service d'Égyptologie et d'Archéologie égyptienne, Université de Liège.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment