http://www.asor.org/anetoday/2018/08/Ancient-Egypt-Sacrifice

Ancient Egypt: A Tale of Human Sacrifice?

By Thomas Hikade and Jane Roy

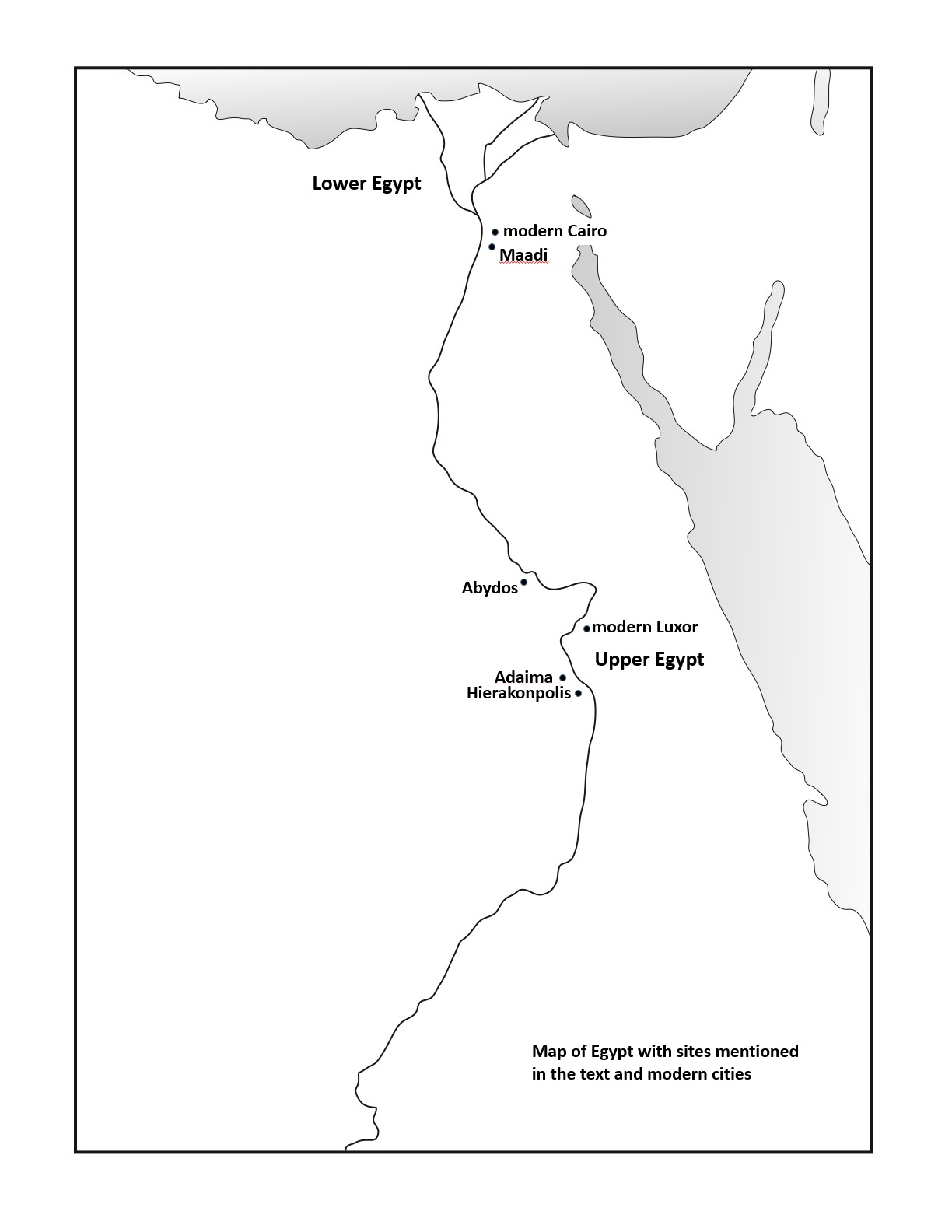

From our modern perspective, the idea of human sacrifice in ancient Egypt is so exotic as to be desirable. But what evidence would really indicate the practice in ancient Egypt? Is it to be found in the pathology of buried individuals, the architecture, the iconographical record, or in oral and written tradition? Are other interpretations equally if not more valid? Our discussion focuses on the early sites of Adaima, Hierakonpolis, Abydos, and Maadi.

Map of Egypt showing sites mentioned in the text. Courtesy of the authors.

Adaima lies about 550km south of Cairo and was primarily excavated between 1989 and 2005. Its two cemeteries contain almost 900 Predynastic graves studied by osteoarchaeologists and anthropobiologists. Some skeletons showed clear cut marks on the upper vertebrae and it seems that skulls were removed after decomposition. But does this constitute human sacrifice?

Predynastic Hierakonpolis, about 20km south of Adaima, has yielded the most intriguing finds from the 4th millennium BCE. Hierakonpolis was the legendary capital of Upper Egypt in the 4th millennium BCE and the major cult centre for the falcon god Horus whose earthly human incarnation was the divine reigning king of Egypt, seen as the shepherd of his people.

The 'working class' Cemetery HK43, (ca. 3600-3400/3300 BCE), contains around 450 burials. Around 3% of individuals show lacerated vertebrae indicative of decapitation, and the skeletal remains of a 20-35 year old male also exhibits cut marks on the skull similar to those at Adaima. It is possible that we are seeing a similar ritual as at Hierakonpolis, but there is no evidence this was done prior to death; the sacrifice of a living human cannot be proven.

The case is slightly different at the elite Cemetery HK6, especially Tomb 16. It is part of a larger funerary complex that contained at least 12 surrounding tombs for humans and at least 10 tombs for animals. While there is evidence to indicate that Tomb 16 and its neighbouring burials were fenced in at the same time, does this mean that all burials happened at the same time? Does it follow that the peripheral tombs were all sacrificial? The appearance of a large and wealthy central burial and its surrounding graves seems to be similar to Adaima, where over the course of time a central tomb became the focus and preferred burial place of succeeding generations of high status people. Retainers seem to have followed their master into the afterlife but just when this journey to the afterlife began for the retainers remains an open question.

By the end of the 4th millennium BCE we can detect centres in Upper Egypt such as Hierakonpolis and Abydos, sometimes called 'proto-states,' which fought for supremacy in the south of Egypt. The political and societal processes that led to a united Egypt are still debated but perhaps can be seen simply as a case where 'big fish eat little fish.'

It is at Abydos where the early rulers of a unified Egypt ultimately found their final resting place. Abydos was the royal cemetery for all the rulers of the 1st Dynasty (c. 3050 -2850 BCE), and the last two kings of the 2nd Dynasty around 2700 BCE. All the tombs were disturbed prior to modern excavation. The royal cemetery was also seen as the burial ground of Osiris, god of the underworld, and from c. 2000 BCE onwards, Egyptians made pilgrimages to Abydos where they left offerings for the god by the tens of thousands, often pottery vessels; hence the site is also known in modern times as Umm el- Qa'ab (Arabic for 'Mother of Pots').

Excavations began in the late 19th century, and from the 1970s until recently the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) re-excavated the cemetery. For the royal tombs, large pits of various sizes were dug into the solid sand and lined with mudbrick walls. Over time the tombs grew considerably and the central royal burial chamber was surrounded by dozens if not hundreds of subterranean subsidiary chambers for graves and storage.

Cemetery U and the Royal Cemetery at Abydos. Courtesy of the authors.

The first tomb, which belongs to King Narmer, consists of two rectangular chambers cut into the desert floor and lined with mudbricks. No smaller chambers accompany Narmer's tomb; it was his successor, King Aha who added this feature. In the case of King Aha three chambers were made for the king's internment and for grave offerings. Northeast of them are a further 36 subterranean chambers containing the skeletal remains of young men but also of several pet lions. The relative youth of these men has led to speculation that they were sacrificial burials to accompany the king into the afterlife. However, the poor preservation of the human remains makes this impossible to verify.

After Aha the royal tombs of the 1st Dynasty increased dramatically in size. Aha's successor King Djer had rows of more than 300 chambers laid out around the royal burial chamber. From the time of King Den on there is a steady decline of the numbers of subsidiary graves and by the end of the 1st Dynasty under King Qa'a there were only 26 such chambers. Some were mere storage rooms for grave offerings but others clearly once contained the burials of retainers.

View of the tomb of King Qa'a. Photos by the authors.

View of the tomb of King Qa'a. Photos by the authors.

Subsidiary chambers of the tomb of King Den. Photos by the authors.

Subsidiary chambers of the tomb of King Den. Photos by the authors.

A second complementary part of the Royal Cemetery were the so-called funerary cult enclosures that were located around 1.5km to the north of Umm el-Qa'ab. These were giant rectangular mudbrick buildings that also possessed hundreds of subsidiary chambers, a minimum of about 1400 in total.

| King | Estimated regnal years | Subsidiary chamber at tomb | Subsidiary chambers at enclosure | Average dead persons per year |

| Narmer | ? | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Aha | ca. 32 | 36 | 6 | minimum of 1 |

| Djer | ca. 47 | 306 | 269 | ca. 13 |

| Djet | ca. 13 | 174 | 154 | ca. 25 |

| Meretneith | ca. 5-10 | 41 | 79 | 12-24 |

| Den | ca. 47 | 121 | unknown | minimum of 3 |

| Anedjib | ca. 6 | 63 | unknown | minimum of 11 |

| Semerkhet | ca. 8 | 64 | unknown | minimum of 8 |

| Qaà | ca. 25 | 26 | unknown | minimum of 1 |

| Total | minimum of 183 | 851 | 509 | n/a |

Table 1. Estimated average subsidiary burials at Abydos during the 1st Dynasty.

But there is no conclusive archaeological evidence that firmly supports the interpretation that retainers were buried together with the king.

The alternative

Unsurprisingly, studies on skeletal material from Umm el-Qa'ab have revealed that small children and women of child bearing years were at greater mortality risk. It seems obvious that malnutrition, diseases such as tuberculosis, and domestic violence are major factors for the short life expectancy in ancient Egypt; reaching the age of 30 was an uphill battle for most of the population. Thus the age distribution of burials at the tomb of King Aha, for example, is very much according to the standard one. An estimate for the construction of the tomb of King Qa'a gives a minimum of two years. Some of the larger royal tombs certainly took longer. But no matter when the construction started there was always ample time for servants of the royal household to 'simply die'.

We propose a straightforward solution to explain the many hundreds of retainer burials during the 1st Dynasty in Egypt: members of the royal households and some of the nobility received the privilege of serving their masters in the afterlife. They died natural deaths during the reign of a king, were buried, and then later re-interred at Abydos.

To sum up: as long as we have no clear evidence of a violent and/or common death from the skeletal remains, the final proof for human sacrifice in the 1st Dynasty in Egypt is missing. People may have been buried in one place at the same time but it does not necessarily follow that they died (or were deliberately killed) at the same time.

Predynastic Maadi and a surprise modern find

Just south of Cairo lies the modern city of Maadi, which is also the name for a prehistoric site of the 4th millennium BCE. Excavations in the settlement and cemetery took place throughout the 20th century. Overall the cemetery at Maadi gives no insight into any violence that might have caused the death of any individual. There is however one occurrence to be mentioned where the body had apparently been treated before internment: the body of a young man between 17-21 years of age was apparently cut in half before being placed in the tomb. And here modern finds from the site sheds light on ancient practices.

During World War I Maadi was the campsite of the Australian 1st Light Horse Brigade and later the 2nd Light Horse Brigade. While working with the German Archaeological Institute in 1999, we were quite surprised when we discovered sheets of modern newspapers alongside finds from the 4th millennium BCE. One was the Cootamundra Libera – Cootamundra being a rural town in New South Wales – dated to Wednesday, 9 December 1914. Among the advertisements for farm equipment, community meetings and general news one can read about what awaited the Australians on the battlefield:

'… he [Stanley Anderson from New Zealand] says that the men who were in the South African war declare that the war was a picnic compared with this. "We have been having a fairly busy time of it', he writes, 'and I think we have given the Germans a busy time, too. They don't like standing up to the British soldier. We had a hot time of it at Mons and Le Cateau, but we gave them more than we got. The Germans came up to us in thousands and went back in hundreds. This is not the old style of fighting with a battle once a month. We have been at it continuously, or nearly so, for the last five weeks, and sleeping besides the guns in the trenches where we now are. The Germans have a big siege gun, which we have christened "Little Willie", and it is throwing shells around us that make a hole in the ground you could bury a horse in.'

Remains of the Cootamundra Liberal, 1914, found at Maadi. Photo by the authors.

Remains of the Cootamundra Liberal, 1914, found at Maadi. Photo by the authors.

Australia had a population of around 4 million at the time of WWI. Around 416,000 men between the age of 18 and 44 enlisted which was almost 40% of this age group. Australia suffered a casualty rate of 65% relative to the number of total embarkations – the highest rate of all countries in World War I!

The Australian soldiers, nicknamed 'diggers', who left Australia for Egypt towards the end of 1914 could not foresee their fate on the battlefields of Europe and the Near East. Yet reading the newspapers they were pretty aware of the grim and fierce fighting that was ahead of them – as did the young soldier who brought a copy of the Cootamundra Liberal, and left it not far from the burial of a similarly aged man who was manipulated in death, and perhaps in life.

Human sacrifice was a rare ritual in past, undertaken by only a few cultures around the globe, as with the case of the Royal Cemetery of Ur. Yet sacrifice to protect your family, people, and country is experienced in the modern world on a far grander scale.

Thomas Hikade is a Researcher at the Nicholson Museum at the University of Sydney. Jane Roy is currently National Cancer Content Manager at Cancer Council Australia.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment