https://gizmodo.com/ancient-egyptian-mummified-hawk-is-actually-a-stillborn-1826487039

High-resolution micro-CT scanning has shown that an Egyptian mummy thought to be a bird is really a stillborn human baby, a surprising discovery that's providing a rare glimpse into the complex cultural practices that existed some 2,100 years ago.

For the Western University anthropologists who analyzed the mummy, it's a fascinating glimpse into ancient Egypt, but for the family who endured this loss, it was a heart-wrenching tragedy—so much so that the family took the time to wrap the stillborn baby in cloth and place the remains inside a small coffin for posterity.

The coffin. Image: Western University

The coffin. Image: Western UniversityBut had it not been for the CT scan in 2016 of a 2,300-year-old mummy known as Ta-Kush, the discovery of this stillborn baby would likely not have happened. While working on Ta-Kush, curators at the Maidstone Museum decided to scan a bunch of other artifacts, including a strange, tiny coffin labeled, "A mummified hawk with linen and cartonnage, Ptolemaic period (323 BC - 30 BC)." To their surprise, the scans did not reveal a bird, but instead the distinct outlines of a premature human baby.

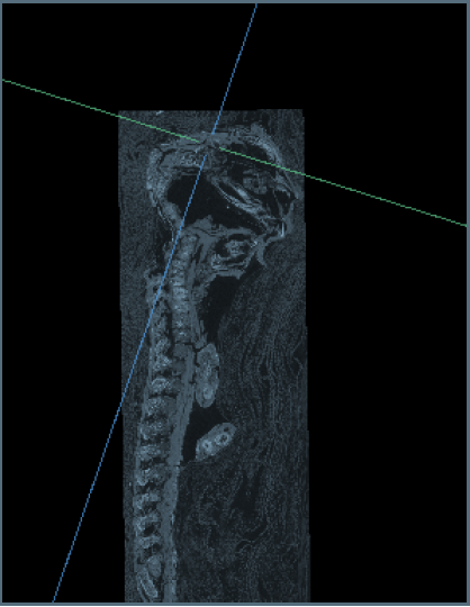

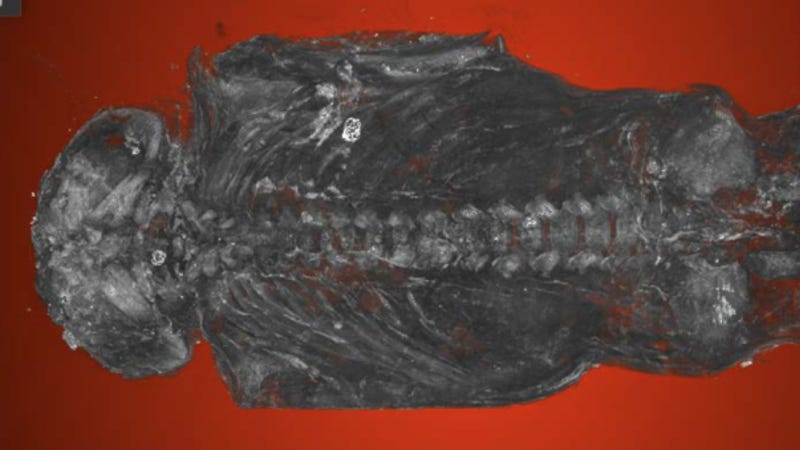

When it comes to visual detail, CT scans are good but not great, prompting Western University anthropologist Andrew Nelson to take a closer look using high-resolution micro-CT scanning. Opening the coffin and handling the remains was not considered an option, given the fragile state of the mummy, but micro-CT scans are the next best thing, as they allow scientists to zoom in and out of solid objects. The updated analysis was recently presented at the Extraordinary World Congress on Mummy Studies in the Canary Islands, and the new scans are considered the highest-resolution images ever taken of a mummified Egyptian fetus.

The preliminary analysis done in 2016 suggested the baby was stillborn, but not much was known outside of that. Nelson and his team of interdisciplinary experts identified the baby as a male who was between 23 to 28 weeks of gestation at the time of miscarriage, and not 20 weeks as previously suggested. What's more, the fetus suffered from a severe form of anencephaly, a condition in which the brain and skull fail to develop normally.

Detailed micro-CT scan of the stillborn baby, showing the malformed skull. Image: Maidstone Museum UK/Nikon Metrology UK

Detailed micro-CT scan of the stillborn baby, showing the malformed skull. Image: Maidstone Museum UK/Nikon Metrology UKIts fingers and toes had formed normally, but the skull was in bad shape. The upper portion of the skull hadn't developed, the arches in its vertebrae hadn't closed, and its ear bones were located at the back of its head. The fetus also lacked bones to form the broad roof and sides of the skull. "In this individual, this part of the [skull] never formed and there probably was no real brain," said Nelson in a press release.

Such finds are rare, as only a half dozen mummified Egyptian stillborn babies are known to exist. It's also one of only two known anencephalic mummies, the other one having been discovered back in the early 19th century. For scientists, the question now is why this family took the extra time, energy, and effort to mummify a miscarried baby.

"As an anthropologist I'm interested in what that means culturally," Nelson said in an interview accompanying the press release. "But certainly fetuses had a role in magic in ancient Egypt, and so there may have been an aspect of that in play here. It would have been a tragic moment for the family to lose their infant and to give birth to a very strange-looking fetus, not a normal-looking fetus at all. So this was a very special individual."

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment