http://asorblog.org/2018/01/16/earliest-music-ancient-egypt/

The Earliest Music in Ancient Egypt

By: Heidi Köpp-Junk

Music is a human universal. Already by the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE a great number of Egyptian texts and images referred to music and musicians, and attest to a complex hierarchy of musicians. But the beginnings of Egyptian music are much earlier. What were the types of musicians and instruments in Ancient Egypt, how were they used, and where did they come from?

Musicians

The social status of musicians is demonstrated in three ways. First are the monuments that the musicians erected or dedicated on their own, like the tomb of the flutist Ipi in Dahshur from 2600 BCE. Some musicians are mentioned or depicted on objects in the tombs of others, like the harpist Hekenu and the chantress Iti, portrayed on a false door and dating to 2470 BCE.

In addition to the archaeological record, the status of musicians is obvious from their designations like 'head of a group of musicians,' sometimes even together with official or administrative titles. Texts indicate that male and female musicians were connected to the royal court or to a temple, and some female singers have the title "chantress of a god." But, like today, vocalists could also be booked by private individuals.

Uniform occupational clothing for musicians is not attested. Sometimes, female musicians are depicted splendidly dressed, sometimes rather scantily. From time to time, tattoos are seen adorning female musicians. Moreover, no special hairstyle is known for Egyptian musicians.

Instruments

A great number of instruments were used in Ancient Egypt, known from iconographic, textual, and archaeological sources.

Aerophones, trumpets, flutes, oboes, and clarinette are well-documented. The trumpet was mainly used in the military context, serving the transmission of command signals since at least 1500 BCE. Two trumpets, made of silver and bronze, were found in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Thanks to a recording from the BBC in 1939 we may listen to these trumpets being played.

Membranophones, better known as drums, are attested in the form of barrel drums, and round or rectangular frame drums. The drum is also a military instrument, but it was used in the religious context as well. In addition to barrel drums, round frame drums are likewise attested. They occur quite often, and were used in the religious context. Examples are depicted in the temples of Philae and Dendera, and Athribis.

Idiophones are, instruments whose entire body vibrates, such as clappers, sistra, rattles, bells, cymbals. Rattles were used since earliest times. Clappers were made of wood, bone, or ivory and often have the shape of human hands. A sistrum is equipped with a long handle and a naos or loop formed top. Often, the head of the goddess Hathor is integrated in the instrument. It is known since 2500 BCE. Bells and cymbals appear at the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE, and are attested as artifacts especially in Graeco-Roman times (4th century BCE-4th century CE).

Chordophones are harps, lutes, and lyres. Harps are attested since 2600 BCE, and appear in religious and private contexts, including richly decorated examples. These instruments were played both by men and women in seated or standing positions. Many different types of lyres are known in Egypt since 2000 BCE. The lute consists of a neck and a soundboard made of wood or tortoise, covered with hide.

Musician with a round frame drum in the temple of Athribis (Photo H. Köpp-Junk)

Replica of an ancient Egyptian lute from the time of Tutankhamun, the so called dancer's lute (copyrights photo and instrument: H. Köpp-Junk).

Reconstructing ancient Egyptian music

There was no musical notation system in Ancient Egypt. Therefore, no melodies are known, the Egyptian music has faded away. But song texts have survived, and the analysis of original instruments and their depictions give valuable hints. Moreover, replicas of instruments such as lutes and flutes elucidate the mode of playing. It has been suggested that the music system was pentatonic, with an octave of five rather than seven notes.

Playing replicas of ancient Egyptian instruments has revealed much valuable information. The dancer's lute has six sound holes on its surface; these holes cause the curious posture of the musicians in various ancient depictions, who hold the instrument in the crook of the arm, more precisely on the forearm. Holding it like a modern guitar would have meant that the sound holes would have been covered. Moreover, keeping the lute in the crook of the arm, leads to playing the strings in the forepart of the instrument's body. At this position the fingers of the right hand are exactly above the point of the greatest distance between the strings and the neck, before it narrows towards the headstock.

Due to the sound holes on the instrument it is necessary to hold the instrument on the forearm (copyrights photo and instrument: H. Köpp-Junk).

Due to the sound holes on the instrument it is necessary to hold the instrument on the forearm (copyrights photo and instrument: H. Köpp-Junk).

Ancient Egyptian lutes were played with a plectrum or with the fingers. For concerts in great halls it is recommended to use a microphone for the lute, since the sound from itself is very quiet (copyrights photo and instrument: H. Köpp-Junk).

Replica of an ancient Egyptian lute, showing the distance between strings and neck (copyrights photo and instrument: H. Köpp-Junk)

The Earliest Music in Ancient Egypt

The earliest known flutes were found in Divje Babe 1 in modern Slovenia and dated to the Upper Paleolithic period (ca. 60.000 - 45.000 BCE). The 10 flutes from the Geißenklösterle cave in the Swabian Mountains of Germany are also about 43,000-35,000 years old. The musical activities attested in Egypt are obviously much younger.

In Egypt, rattles are attested in the 5th millennium BCE and appear in sanctuaries and tombs. There are no depictions of rattles being used; rather they only appear as artifacts. Clappers appear in the 4th millennium BCE as depictions on vases. After 3100 BCE they were found as artifacts as well, as for example in the tomb of Pharaoh Djer in Abydos.

The oldest Egyptian flute dates to the 4th millennium BCE and is depicted on the Two Dogs Palette, found in the temple of Hierakonpolis. A human being, possibly a priest with a mask, or a fictive animal in the shape of a jackal, plays the flute, and other animals seem to dance to the music. There is no evidence for Chordophones in the 4th millennium BCE: the earliest iconographic and textual evidence for harps, as well as drums, dates to 2600 BCE.

The evidence shows the earliest instruments in Ancient Egypt were rattles, dating to the 5th millennium BCE, followed by clappers and flutes in the 4th millennium. Harps and drums are only attested in the middle of the 3rd millennium. There seems to be more evidence for idiophones than for melody instruments in the earliest periods.

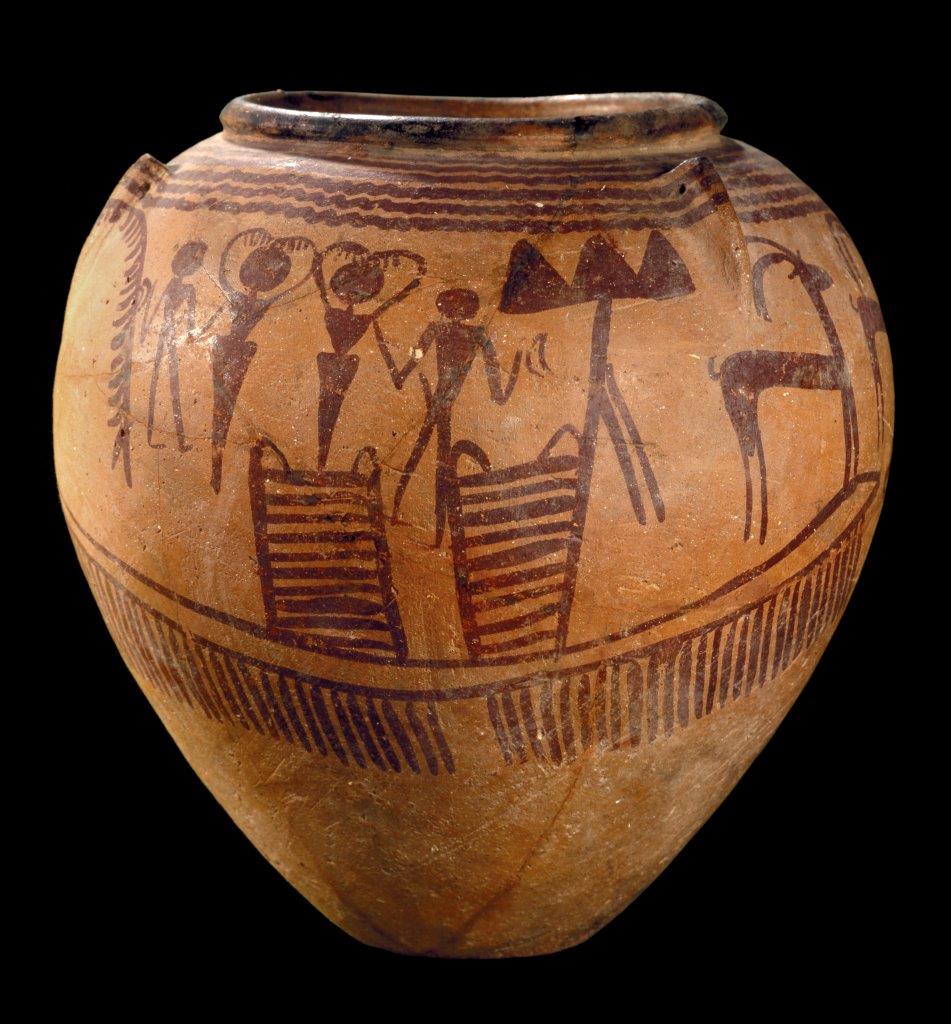

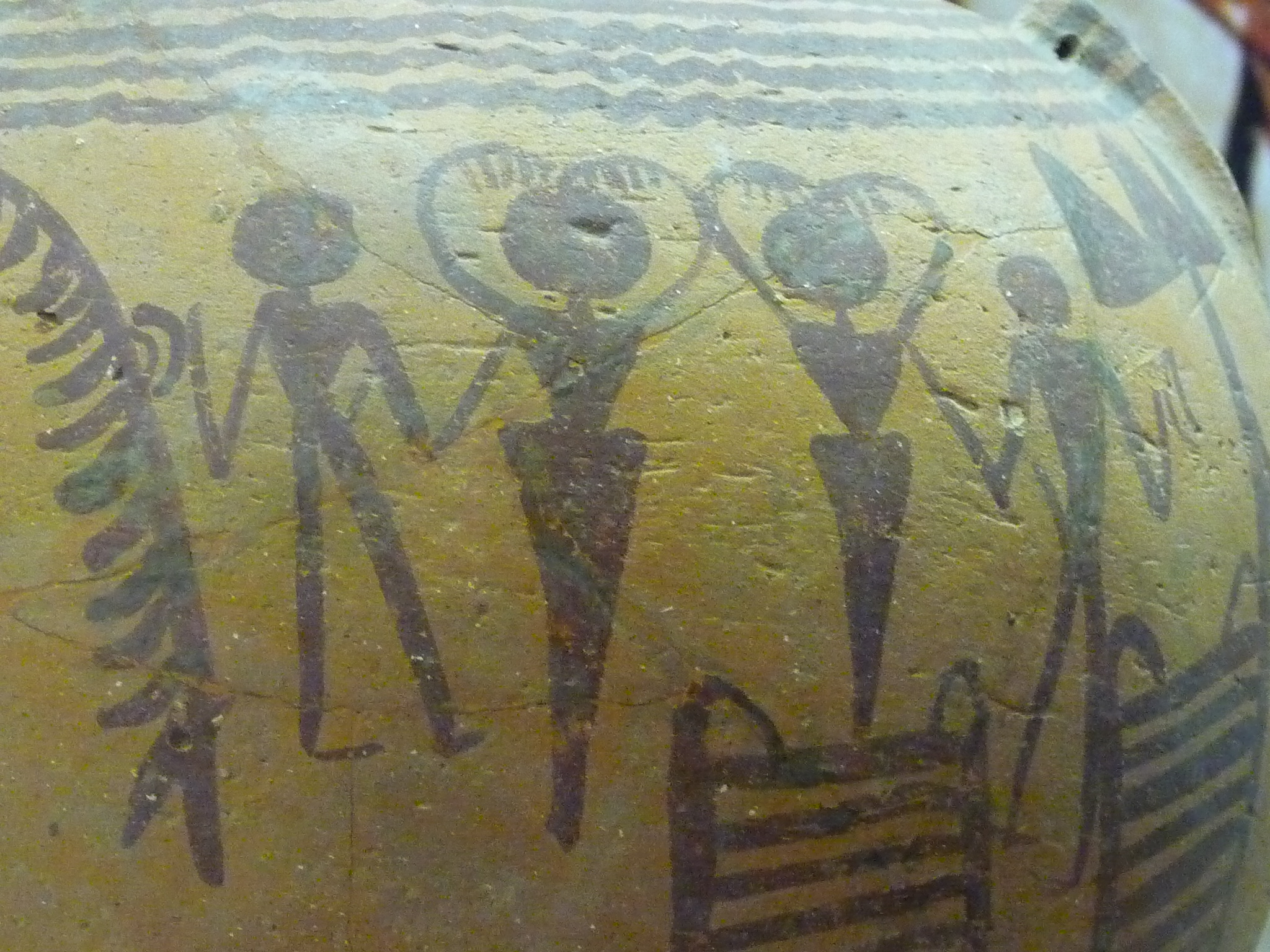

Vessel from the 4th mill BC showing men with clappers (copyrights: Museum August Kestner Hannover, Germany, inv.-nr. 1954.125, photo: Christian Tepper).

Vessel from the 4th mill BC showing men with clappers (copyrights: Museum August Kestner Hannover, Germany, inv.-nr. 1954.125, photo: Christian Tepper).

Context

In these early periods, musical instruments were not only restricted to funerary contexts, but appear in religious settings. Which function they had in the tomb or temple rituals, or how the ceremonies were practiced, is not known. No depiction, even from later periods, shows the use of clappers at a burial. These only appear occasionally in depictions of religious feasts.

In the early periods music is not attested for private entertainment, such as within domestic or family group. But this absence does not imply that music was not practiced in the private context and during everyday events, only that it was not reflected in two- and three-dimensional art. Moreover, at present there is no still evidence for music used entertainment at the royal court.

But there is evidence for music in the religious context. The practice of religion is an important means for individual participants, since it strengthens the emergence and development of a common identity. In early Egyptian history, music as part of religious rituals might have supported the emergence of the Egyptian state as a unit.

Where Egyptian music does comes from?

Music is universal across all human cultures. Hand clapping and singing especially are musical expressions attested in every culture since earliest times. Several instruments like drums, flutes and string instruments are also common in nearly every society.

It is impossible to prove where musical instruments were invented the first. The lute, the harp, as well as the lyre, appear much earlier in the Near East than in Egypt. Therefore, despite the lack of explicit evidence, it is often assumed that the instruments were imported into Egypt. Even the sistrum is not unique to Egypt, since it appears at the same time in Mesopotamia.

How might this be explained? Like today, some ancient musicians were highly mobile, traveling several hundred kilometers. They might have brought the hardware as real instruments back to Egypt, or at least the idea of it, developing it to a special Egyptian version. Moreover, in later periods foreign musicians are attested in Egypt and surely brought their own instruments along, influencing Egyptian musical technologies and styles in the process.

How does understanding music change our larger appreciation of Early Egypt?

Our image of ancient Egypt is shaped in large part by architectural objects like Obelisks, Sphinxes, houses, pyramids and temples, as well as archaeological artifacts as furniture and pottery. But among non-scholars much less is known about the non-material culture of Ancient Egypt, for example literature. The textual evidence shows us more of the inner life of the ancient Egyptians than all the items known archaeologically. Music allows an even deeper insight into the daily life of ancient Egypt. The so-called 'love songs' in particular show that sentimentality and emotional expression in music were not inventions of modern times, but are universal since earliest times. The words of a New Kingdom love song resonates even today:

the man sings of her beauty, and his wish to approach her

the woman, separated, in the house of her mother, sings of her longing for his arrival

the man abandons hope of reaching her

the woman struggles with her desires

after seeing her, the man rejoices but is still separated

after seeing him, the woman sings of her hope that her mother might share her sentiment

seven days of separation have left the man sick: only she can cure him

Imagining such works sung makes the impact even greater.

Video Player

View the full video here.

Heidi Köpp-Junk is a post-doctoral fellow in Egyptology at the University of Trier. Visit her website.

For Further Reading

- Emerit, "Music and Musicians," in Willeke Wendrich (ed.,), Encyclopedia of Egyptology, (Los Angeles, 2013).

- Köpp-Junk, "The artist behind the Ancient Egyptian Love Songs: Performance and technique. In: R. Landgráfová and Navrátilová (eds.), The World of the Ancient Egyptian Love Songs. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, 2015, 35-60.

- Köpp-Junk, "Textual, iconographical and archaeological evidence for the performance of ancient Egypt Music," in A.G. Ventura et al., (eds.), The Musical Performance in Antiquity: Archaeology and Written Sources. (In press).

- Manniche, Music and Musicians in Ancient Egypt. (London, 1991).

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment