Akhnaten Opera Star Is Offered an Egyptology Fellowship at Oxford

Anthony Roth Costanzo takes the role, which he's been playing since 2016, so seriously that it's been academically recognized.

Photographer: Karen Almon/Met Opera

The first time Richard Bruce Parkinson saw Philip Glass's opera Akhnaten, in 1985, he left unimpressed. The tale of Pharaoh Tutankhamun's father and his doomed quest to change Egypt's belief system from polytheism to monotheism struck him as "quite a romantic, quite an idealistic view."

Thirty years and one production later, Parkinson, a professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford and a former curator at the British Museum, is now a superfan. So much so that he's made Anthony Roth Costanzo, the opera's star, a visiting fellow at Oxford's Research Centre in the Humanities.

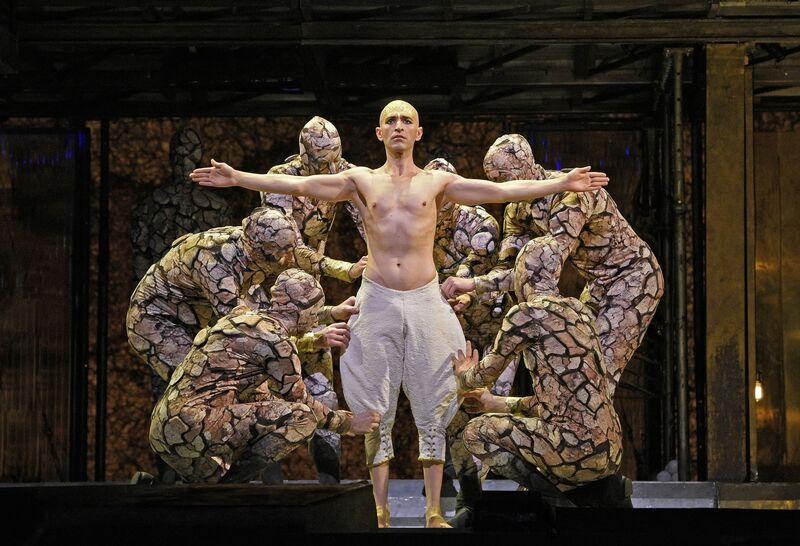

The current steampunk-inflected version of Akhnaten, from director Phelim McDermott with sets by Tom Pye and costumes by Kevin Pollard, has been running since 2016. It will be back at the Metropolitan Opera in New York on May 19 after a season's hiatus, returning with a Grammy win in April for best opera recording. "As an Egyptologist, I should probably be a bit shocked at the liberties it takes," Parkinson says. "But it's done with such imaginative conviction, it's a brilliant approach."

"When they told me about the fellowship," Costanzo says, "I was like, 'You guys know I'm not a real pharaoh, right?' " Upon reflection, he says, "I think it was implicit—and this sounds kind of ridiculous—that I've become somewhat synonymous with Akhnaten at this point."

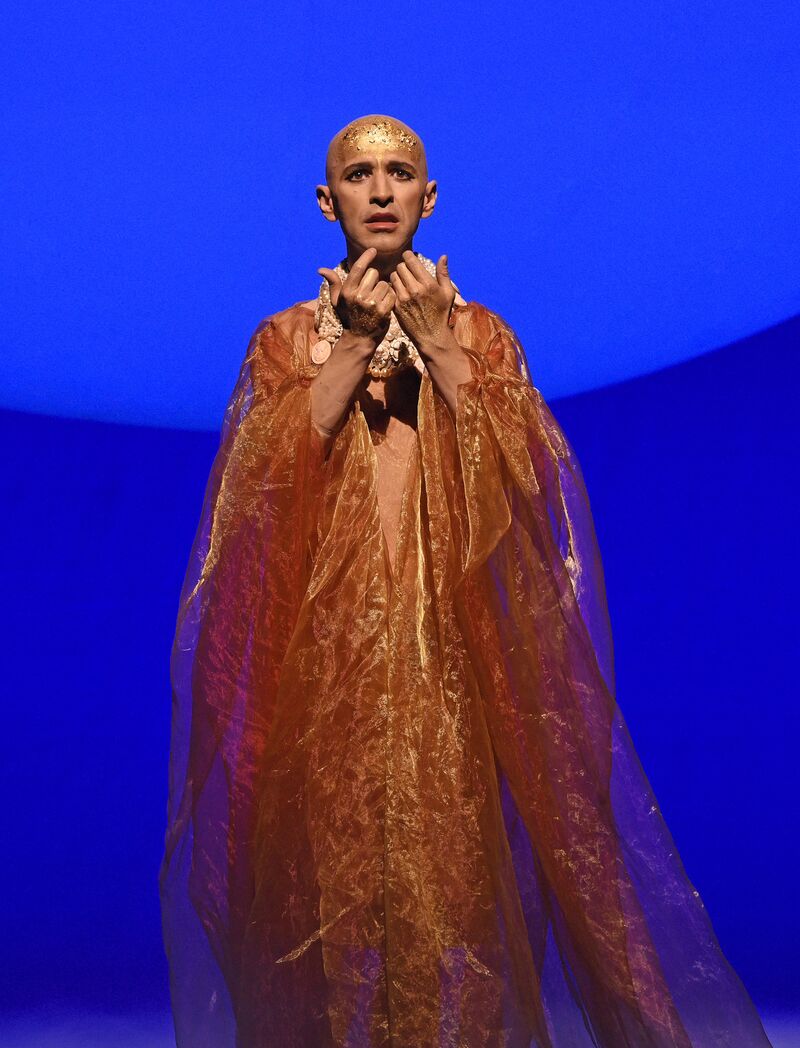

It's not all that ridiculous, actually. Costanzo is one of opera's rare countertenors (a man who sings in a woman's traditional register) and has starred in the role since the current production's 2016 premiere at the London Coliseum. Plus, he even looks kind of like the pharaoh himself. Parkinson says, "If you look at photographs of Anthony during performances and compare them with one of the busts of Akhnaten in the Berlin museum, it's a very good likeness."

More to the point, Parkinson says, Costanzo was given the fellowship (which will take place in November) because Akhnaten and Costanzo's efforts to promote it are helping to change long-held historical biases. "[Ancient] Egyptian culture is beginning to escape from the stereotypes that have surrounded it for so long," Parkinson says. "It's about time. Think of The Mummy. Think of Indiana Jones. They're really, really offensive." Akhnaten, in contrast, positions the pharaoh "as a modernist figure who should be treated seriously as a thinker and human being," Parkinson says.

The best way to describe this production's aesthetic may be soft-edged steampunk with a splash of modernism. It emphasizes Akhnaten's gender fluidity and religious rebellion. And the fairly minimal sets dodge ancient Egyptian clichés: no hieroglyphs or palm trees. Instead, a troupe of jugglers provides the visual drama—a choice that's historically accurate, Parkinson says: "Juggling is very, very clever as an effect. As has often been said, juggling is an art practiced by the ancient Egyptians, so that is in no way anachronistic."

As for the costumes, Costanzo spends the first six minutes of the opera stark naked, a fresh take on the traditional underwear-in-front-of-an-audience nightmare. The rest of the time, Costanzo and the cast are in gauzy robes and headdresses imbued with a Victorian sensibility—a nod to the period of Western culture when ancient Egypt was fetishized. But it was the second-act climax, in which Costanzo sings an aria based on an ancient poem and then ascends a staircase to worship a massive glowing orb, that left Parkinson, a specialist in ancient Egyptian poetry, in raptures. It was "fresh and modern and a serious work of art," he says. "It's a very high-artistic approach to an ancient text that doesn't happen very often."

Audiences agree. When the show opened in London and traveled to Los Angeles, most performances sold out. When it went to New York's Metropolitan Opera in 2019, almost every night was a completely full house. "What I find very inspirational is the idea that what an academic is doing with historic data is the same as what Anthony is doing," Parkinson says. By bringing attention to this role, he adds, "it's different forms of re-creating the ancient experience, but they're the same vision of giving a bit of life back to the past."

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment