A life in Egypt

Faiza Rady, Tuesday 12 Apr 2022

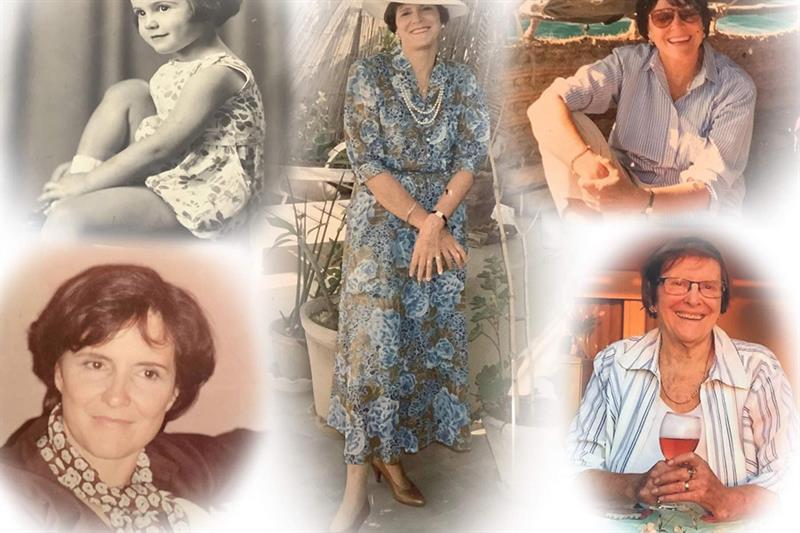

Jill Kamil (1930-2022)

Close long-time friend and colleague, prominent writer and journalist Jill Kamil passed away peacefully in England on 28 March.

Born and raised in Kenya, Jill moved to England in 1951 where she met her husband-to-be, Nabeeh Kamil, an Egyptian artist and professor at Ain Shams University. They married in Germany in 1954, and then settled in Cairo. It didn't take long for Jill to fall in love with Egypt's rich culture and history, and when Jill and Nabeeh Kamil divorced in 1972, she opted to remain in Egypt.

Jill's early years in Egypt were punctuated by frequent camping trips at Ain Al-Sokhna — the warm spring — on the Red Sea. At the time Ain Al-Sokhna was virgin desert land, crisscrossed by the sparkling blue water of the spring and home to flamboyant flowering cacti and other blooming vegetation. Inspired by the area's visual splendour, Jill wrote her first book, The Red Sea.

The book led to Jill's decision to become a professional writer and document Egypt's Pharaonic sites and cultural history. She proceeded to study under the guidance of scholars in the field, including Egyptian Egyptologist Abdel-Moneim Abu Bakr, and professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo Kent Weeks. She was also a student of the eminent archaeologist Labib Habachi, whom she admired and whose biography she wrote.

Jill became a prolific writer of historical guidebooks, beginning with Luxor: A Guide to Ancient Thebes, the first guidebook to look closely at the material remains of a specific site and narrate the art and social history of its inhabitants. Published in 1973, it was followed by Saqqara and Memphis: A Guide to the Necropolis and the Ancient Capital; Upper Egypt: The Antiquities from Amarna to Abu Simbel; Aswan and Abu Simbel, and The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom.

In addition to other works on Egyptology, Jill also wrote several histories of the Coptic Christian Church. Christianity in the Land of the Pharaohs, published in 1985, was hailed as "groundbreaking" by RAWI magazine.

"Drawing on personal travel to all the Christian sites of Egypt, and conversations with scholars, monks, museum directors and scores of lay Egyptians both Copt and Muslim, the author tells us about the fundamental importance of Coptic religion and culture in Egypt. Weaving together historical research with absorbing stories she… offers a captivating insight into a side of Egypt that will be new to many readers," said the magazine.

Labib Habachi: The Life and Legacy of an Egyptologist, published by the American University in Cairo Press in 2007, is another of Jill's groundbreaking works.

"The book provides an Egyptian perspective on archeology over a span of a hundred years," Jill explained in the introduction. It didn't only focus on Habachi's biography, but reviewed the scholarly achievements of his predecessors, including "Selim Hassan (1886-1961), who carried out excavations at Giza that equaled in size and productivity those of any foreign mission working in Egypt at the time; and Ahmed Fakhry (1905-1973), well-known for his pioneering studies on the oases of the Western desert."

Habachi, who ranked among the most insightful and productive of Egyptian scholars in the field, was marginalised for most of his life.

"He had an encyclopedic knowledge of the subject of his specialization, he was an invaluable source concerning the results of fieldwork," wrote Jill. "Habachi struggled relentlessly to carve his way into the annals of a discipline traditionally dominated by Western scholars… many of his most perceptive archeological observations, based on a deep understanding of ancient history… were only recently recognized because they cast doubts on earlier European conclusions."

His most important manuscript, The Sanctuary of Heqaib — containing his findings on Heqaib's mausoleum on Elephantine Island, was shelved in the Egyptian Antiquities Department for 30 years.

"This was to preoccupy Habachi until his death," wrote Jill. The Sanctuary of Heqaib was finally published by the German Archeological Institute in 1984, shortly before Habachi's passing.

Jill spelled Habachi's, and other scholars', marginalisation by the powerful foreign archaeological missions, as well as by the Antiquities Department. She was unafraid to criticise the powers that be, both foreign and local, for suppressing the research and achievements of Egyptian archeologists.

"The study of Egypt's ancient heritage is more closely linked to politics than may be generally supposed," wrote Jill — who courageously challenged the establishment by writing Habachi's biography "from an Egyptian perspective".

Jill's love of the country and its heritage, and her commitment to include people's voices in her writing, shaped her identity as an Egyptian. As a Kenyan she also had African roots. Jill travelled extensively to Sudan, Uganda, and Tanganyika, and maintained a lifelong interest in, and understanding of, African cultures from the source of the Nile in Lake Victoria to its exit in the Mediterranean.

She regarded herself as an African-Egyptian. At Al-Ahram Weekly, where she worked as the editor of the Heritage page and covered archaeological findings, she would often remind her colleague and friend, Gamal Nkrumah — the son of former Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah and his Egyptian wife Fathia Risk — that they were the only African-Egyptians working at the paper. Their shared sense of identity created a special bond between them, and they would often discuss African history and politics, a topic of passionate mutual interest.

Jill's work was highly regarded at the paper, where she worked from 1994 to 2010. She was especially supportive of younger colleagues.

Reem Leila, now an established journalist, remembers her first professional encounter with Jill:

"I have always respected and cherished this lady. It happened that I once wrote an article for her page, and it was my first time. I remember her telling me: 'I loved your piece, you have written it as an expert.' I never forgot the look in her eyes as she thanked me for the article."

Amira Noshokaty added: "I have known Jill since I was a fresh graduate. She was always smiling and generous with her thoughts and words. We shared the same room for years. She was young at heart, knew Egypt inside out, and kept encouraging me to take walks, and to take the road less travelled. Every story I wrote back then made me discover myself."

Reham El-Adawi recalled that, on arriving to work at the paper, Jill immediately made her feel safe. "Jill encouraged me to travel to areas I had never been before. She taught me everything about travel writing. She encouraged me to talk to the excavators she knew who were working at particular sites, and taught me how to tour a museum — often little known museums — and write about it."

Jill Kamil is survived by her second husband, Michael Stock, a retired British diplomat; her daughter Tamara Rostom who lives in Denmark; her son Waheeb (Ricky) Kamil and his wife Christine who live in the US; her grandchildren: Natasha, Nadine and her husband Peter Hansen, Dina and her fiancé Nicklas Graversen, and Marc; great-grandson Tristan; her sisters, Dorothy in South Africa and Suze in London, and her brother, John in Los Angeles.

* A version of this article appears in print in the 14 April, 2022 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment