Moving Egypt's Ancient Obelisks

1536

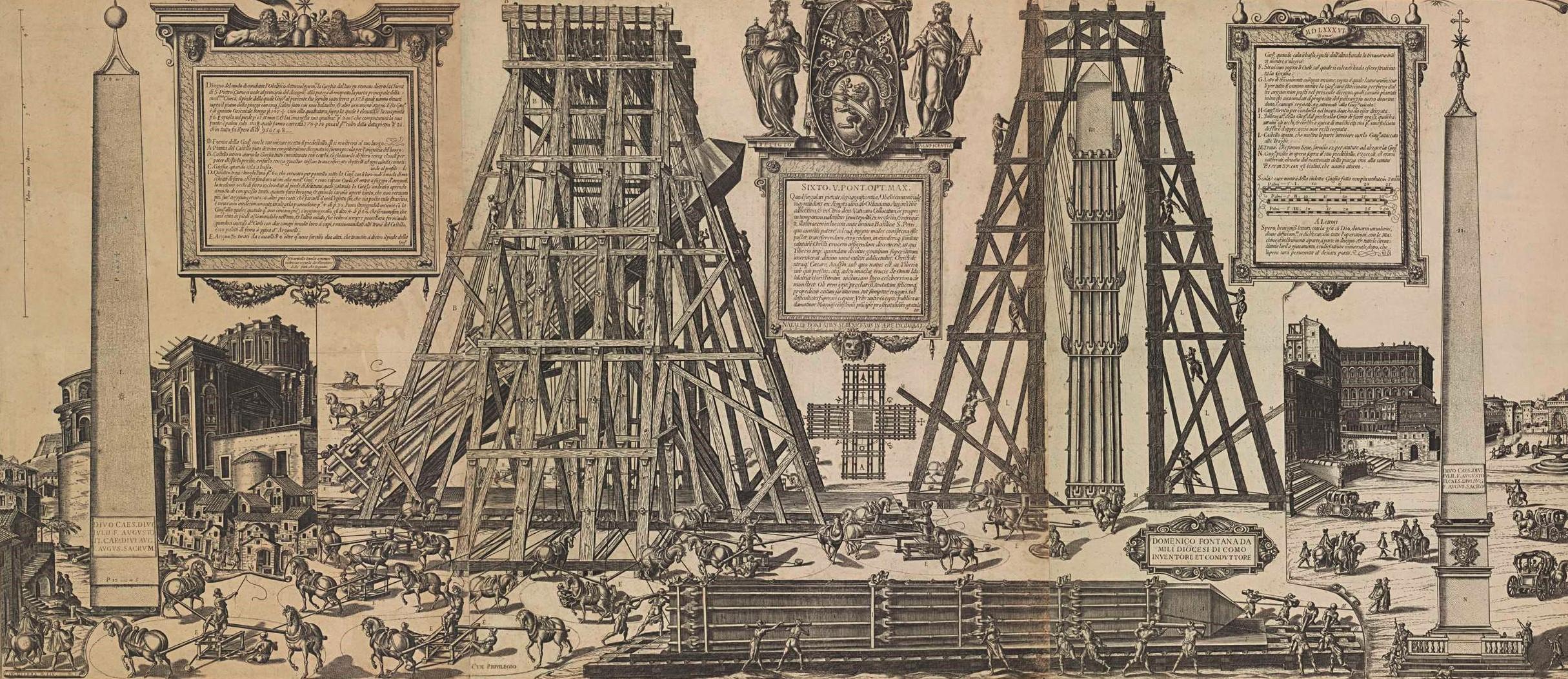

1536 Natale Bonifazio da Sebenico, Moving the Obelisk of St Peter's Basilica, 1586.

What do Central Park in New York, the Embankment of the River Thames in London, Place de la Concorde in Paris, Sultanahmet Square in Istanbul, and Piazza San Pietro in Rome have in common? All of them feature an Egyptian obelisk. But how did these monuments of the ancient Pharaohs end up in modern metropolises?

Connected to solar worship, obelisks, or tekhen, were a distinctive feature of Egyptian temple architecture for over two and a half thousand years, from the third millennium BC to the first century BC. Varying in height from just a few meters to over thirty, obelisks are monoliths, carved out of a single piece of granite. The enormous stones were quarried at Aswan in Upper Egypt and then transported to cities and temples further up the Nile; yet for some, the journey did not stop there.

In 30 BC, the Kingdom of Egypt was annexed as a province of the Roman Empire, following the defeat of Queen Cleopatra by the future emperor Augustus. The victorious Augustus transported two obelisks from the Egyptian temple at Heliopolis back to Rome. One was set up to adorn the central barrier (spina) of Rome's chariot racing track the Circus Maximus, while the other served as the pointer (gnomon) on a vast solar calendar. Subsequent emperors continued the trend of importing obelisks to Rome, taking some from existing Egyptian temples as well as commissioning the carving of new ones, and thirteen can still be found in the Italian capital.

Pedestal of the Obelisk of Theodosius I in Istanbul, showing the moving of the Obelisk.

Where you see obelisks in Rome today, in the center of piazzas and on top of statues and fountains, are not where the emperors originally placed them. Whether by accident or vandalism, most obelisks were thrown down in the centuries after the end of the Roman Empire, to be later excavated and re-erected by the Popes of the Renaissance and Baroque periods. These were then moved to new locations across the city, in some instances to serve as the focal points of new streets, and with the addition of bronze crosses fixed to the top, symbolizing their appropriation as Christian monuments.

During the rebuilding of St Peter's Basilica in the sixteenth century, Pope Sixtus V sought to move the obelisk first brought to Rome by the emperor Caligula 1,500 years earlier to ornament his race track on the Vatican hill. The obelisk had to be lowered, transported a few hundred meters, and then raised again in front of the church. Despite the short distance, the undertaking was extremely risky–the obelisk weighs over three hundred tons and moving one of this size had not been attempted since antiquity. The task took several months and required over 800 workers, approximately 140 horses, and forty custom-made cranes. At the key moments of its lowering and raising, crowds of locals and visitors watched the spectacle, with the achievement of moving the obelisk seen as important as the monument itself.

The Vatican Obelisk, St Peter's Basilica

This interest in the feats of engineering required for relocating obelisks goes back to ancient Rome. Indeed, so impressive were the purpose-built ships that carried the obelisks for the emperors Augustus and Caligula that the vessels were preserved and exhibited as marvels in their own right. The obelisk that now stands in Sultanahmet Square arrived in the city of Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, towards the end of the fourth century AD. It was already 1,800 years old, having been carved during the reign of the Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1426 BC), and was brought over to adorn the central barrier of the city's chariot racing track. On the base of the monument, inscriptions boast how it was transported and erected in the course of just one month, and a carved relief depicts the obelisk on its side while figures work ropes and pulleys to raise it into place.

An analogous scene of engineering decorates the pedestal of the obelisk in Paris. When Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt in 1798, the French army was accompanied by 167 scholars and painters, whose work popularised the culture of ancient Egypt in Europe. Egyptian antiquities became highly sought after, and in the early 1830s, the French government arranged for the acquisition of a pair of obelisks flanking the entrance to Pharaoh Rameses II's (1292–1190 BC) temple at Luxor. Only one arrived and it now stands at the end of the Champs-Élysées opposite the Arc de Triomphe (the other, now looking somewhat lonely, is still at Luxor).

The remaining Obelisk at Luxor, Egypt, 1881.

The Paris obelisk is one of three sometimes called, erroneously, 'Cleopatra's needles', the other two being in New York and London. The New York obelisk was originally erected by the Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1426 BC), like that in Istanbul. It was raised in Central Park in 1881, having been secured by diplomatic negotiations with the Egyptian government, and apparently in response to Britain's efforts to transport one to London.

153615361536

153615361536 Pedestal of the Luxor Obelisk, Paris, showing the moving of the Obelisk

Four bronze plaques surround the base of the obelisk in London and tell the story of how it came to be there. Quarried in the fifteenth century BC by Thutmose III (again!), the hieroglyphs down the shaft were added two-hundred years later by Rameses II. Over a millennium after this it was moved from Heliopolis to Alexandria, where it was re-erected in the reign of Rome's emperor Augustus in 12 BC. Reportedly 'prostrate for centuries on the sand of Alexandria,' it was gifted by the Viceroy of Egypt to the British in 1819 in recognition of their defeat of Napoleon in Egypt two decades earlier. Yet the effort to move the obelisk to Britain was not made for a further fifty years. It was almost lost in a storm en route, which cost the lives of six men, and was eventually raised next to the River Thames in 1878, where it still stands. Its long history shows that repurposing obelisks was nothing new.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment