https://news.uchicago.edu/story/oi-marks-100-years-discovery-ancient-middle-east

Museum, scholars have shaped study of earliest civilizations

A century ago, a few lone scholars began arguing a controversial idea: Western civilization had its roots not in Greece and Rome, as academics had maintained for centuries, but further back—in the sun-drenched lands of the ancient Middle East.

That idea was at the center of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago when it was founded in 1919. Over the course of the next 100 years, the OI has changed how humans understand their own history through groundbreaking work in archaeology, linguistics, and historical and literary analysis—work that continues today in Chicago and across the Middle East.

"The ancient Middle East is part of our origin story. This is the place where humans created the first villages, cities and eventually empires, and along the way developed essential technologies that form the basis of today's world, such as the domestication of plants and animals and the invention of writing," said Christopher Woods, the John A. Wilson Professor and director of the OI, and a leading scholar of Sumerian language and writing. "In many cases, what was created in Mesopotamia influenced our world, and the OI's work over the past century has been essential to understanding these cultural threads."

Scholars at the OI laid the foundations for the modern study of the ancient Middle East, with the work assuming an extraordinary array of forms: innovative, field-defining excavations and research projects across the Middle East; linguistic research that furthers the decipherment of ancient languages; the creation of cultural encyclopedias for long-lost civilizations; state-of-the-art satellite and digital imaging methods for the discovery of ancient settlements; and centers for the documentation and preservation of the region's imperiled cultural heritage. The work continues today through excavations and research projects led by OI scholars in places such as Egypt, Iraq, Turkey and Afghanistan, as well as scholarship to reconstruct histories, literatures and religions of long-lost civilizations.

The research of the OI has uncovered new ways of seeing what connects humans and why—providing insights and perspectives not just into the ancient world but on the challenges we still face today, from environmental change to immigration to disruptive technologies.

"There, in the Fertile Crescent, human beings forged something remarkable: a collective identity and life," Woods said. "To become "we," they had to decide who leads, which ideas and behaviors to encourage and which to punish, and where they stood together in the world and in the cosmos—in other words, how to become humans, together."

"The ancient Middle East is part of our origin story. This is the place where humans created the first villages, cities, and eventually empires."

This knowledge is on display at the Oriental Institute Museum, which is home to 350,000 artifacts—making it the largest collection of ancient Middle East artifacts in the United States. A distinguishing feature of the museum's collection is that it was primarily excavated by OI archaeologists rather than purchased.

As the institute celebrates its centennial, the OI is reflecting on this remarkable journey—and offering a range of activities to the public.

From Egypt to Chicago

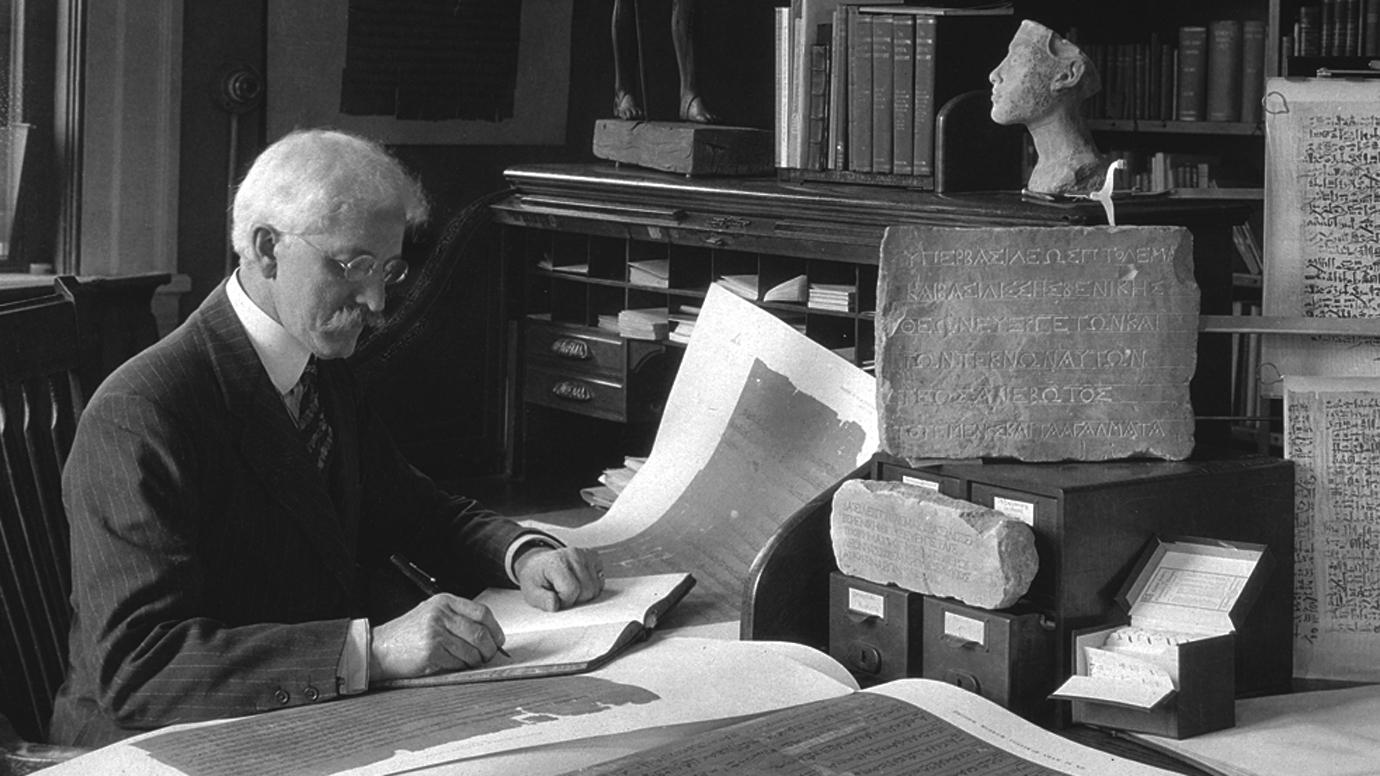

In 1919, James Henry Breasted, the founder of the OI, set off on an eleven-month trip across the Middle East. Traveling by sea, land and air, he was one of the first Western scholars to explore extensively a region that he would later vividly describe as the Fertile Crescent. This trip shaped the work of the Oriental Institute for decades and would change how the ancient Middle East is studied and understood.

Breasted brought thousands of artifacts to Chicago. One of his favorites: a 35-foot-long scroll containing the ancient collection of magical spells called the Book of the Dead, recently displayed in its full extent in a special exhibit. "I could hardly believe my eyes, for I saw something which I have never seen in all my years in Egypt—a beautiful roll of papyrus, as fresh and uninjured as if it had been a roll of wallpaper just arrived from the shop!" he wrote of the 2,200-year-old manuscript.

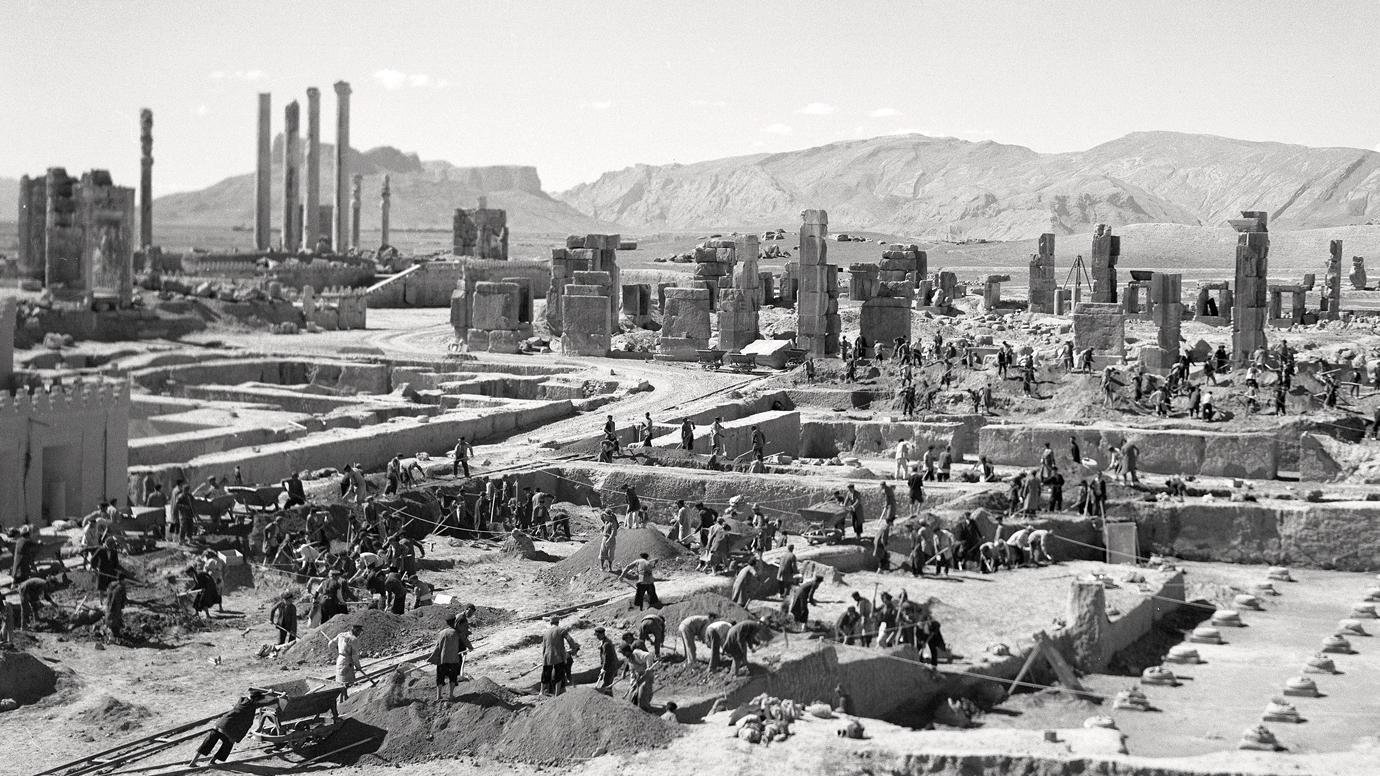

Since then, the OI has organized archaeological and survey expeditions to nearly every country of the Middle East. These excavations have defined the basic timelines for many ancient Middle Eastern civilizations and made fundamental contributions to our understanding of basic questions in ancient human societies, ranging from the origins of farming and sedentary life to the study of urbanism and the rise of the world's first empires.

Today, OI archaeologists are uncovering Iron Age kingdoms in Turkey, prehistoric and Phoenician cities in modern-day Israel, and one of the last well-preserved ancient Egyptian towns at Tell Edfu. They're also returning for the first time in 30 years to Nippur, a site in modern-day Iraq that was the religious center of ancient Mesopotamia.

An increasingly important part of this work in the Middle East is cultural heritage preservation. For example, OI scholars are partnering with the National Museum of Afghanistan to inventory the museum's holdings for the first time, as well as restoring over 6,000 fragments of Greco-Buddhist sculptures that were smashed by the Taliban but saved by the Kabul museum staff.

A dictionary for a civilization

Of course, a culture is much more than the objects it leaves behind.

Archaeologists found hundreds of thousands of clay cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia, but knowledge of the ancients and their lives exploded a thousand-fold when these languages were finally deciphered. Now scholars can read everything from the great tales of the day (such as the hero Gilgamesh's quest for the secret of immortality) to complaints about cheating merchants (the shady business practices of one 18th century B.C. entrepreneur named Ea-Nasir are particularly well-documented).

This cuneiform writing system survived for more than 3,000 years, with the Hittite, Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires adapting the script to express their languages. Naturally, it evolved quite a bit over three millennia. Hence one of the OI's primary research missions: to document the rich textual sources into "dictionaries" that are much more than a listing of translations as they describe the cultures, histories and religions of ancient civilizations.

The Chicago Assyrian Dictionary was one of the first priorities for the OI; Breasted himself initiated the groundbreaking project in 1921. Completed 90 years later, the dictionary was a remarkable collective effort and represented one of the greatest humanistic endeavors of the 20th century, combining the efforts of an international community of scholars over generations.

The OI is also home to the Chicago Hittite Dictionary, cataloguing the Hittite language, which is attested between 1650 and 1180 B.C. and is the oldest Indo-European language we know—predating Greek, Latin and Sanskrit. Another project maps Demotic, a script used in ancient Egypt alongside hieroglyphs for more than a thousand years. And in Luxor, Egypt, a team works to rigorously document the inscriptions and images on temples in the area, pioneering a process combining old and new technology and termed the "Chicago method."

Art and archaeology on display

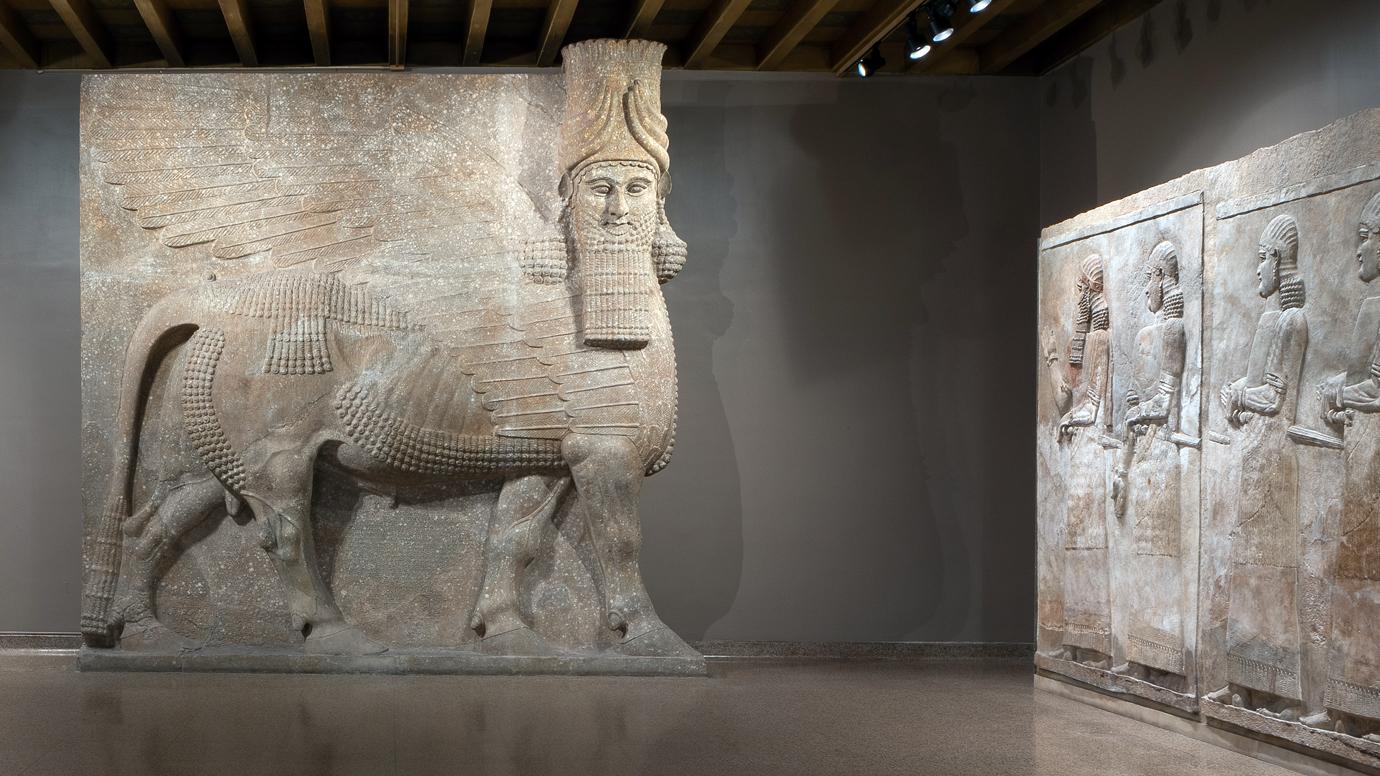

The fruits of these labors can be seen at the OI museum, with roughly 5,000 artifacts on display on the campus of the University of Chicago. The scope of the museum follows the growth and journey of the earliest civilizations and empires—from stone tools at the dawn of agriculture to the iconic 40-ton winged bull from the palace of the Assyrian king Sargon II.

Because the artifacts are the products of carefully-considered research questions, the collections provide an unparalleled resource for scholarly research. These meticulous records that make up the museum archives allow for a richer understanding of the objects and thoroughly document their archaeological context; for example, the OI recently helped prove an artifact up for auction by an art dealer in Manhattan had actually been stolen from the site of Persepolis in modern-day Iran long ago in the 1930s.

A multiyear renovation project has focused on updating the displays and spaces of the museum's galleries. Over 500 new objects have been put on display, and the OI is planning special collaborations with contemporary artists to celebrate the centennial.

Among the new objects on display will be a 3-foot-tall stone sculptural fragment of the head and horned crown of a monumental human-headed winged bull from King Sargon II's palace; a fragment of an early Islamic manuscript that contains the oldest known text of A Thousand and One Nights; and an exhibit on making and drinking beer in ancient Mesopotamia.

Special events are planned throughout the fall, including a public centennial celebration on Saturday, Sept. 28 and a full program of talks, tours and films.

Woods hopes that all visitors leave with new information about the ancient world, and a new perspective on our own.

"Over the course of 10,000 years, you see people deal with disruptive technologies, issues of immigrations, tensions between secular and religious institutions, economic crises, and climate change," Woods said. "It gives you a certain insight, a very high-elevation perspective to see that we still deal with some of these problems today. It makes you realize—nothing truly is new under the sun.

"Some of what people in the ancient Middle East created, experienced and believed feels intimately familiar—we can see ourselves reflected in this ancient mirror," he said. "But even when their perspectives feel worlds and ages removed from our own, they have so much to teach us about what it means to be human."

Sent from my Linux system.

we highly appreciate OI Collection for research, Abdul Razzak,ARCHAEOLOGIST,BAGHDAD

ReplyDelete