https://egyptmanchester.wordpress.com/2018/07/06/curators-diary-june-2018-up-close-with-the-sphinx-ancient-and-modern/

On 07/06/2018 07:53 AM, Campbell@Manchester wrote:

Curator's Diary June 2018: Up Close with the Sphinx, Ancient and Modern Last month I had the chance to spend a couple of days in close proximity with the Great Sphinx at Giza whilst filming a documentary for Discovery Channel (a crash course in pithy communication, ideal for museum curators). Unrestricted admittance to the Sphinx enclosure (usually off-limits to visitors) prompted me to consider the degree of access ancient people might have had to this iconic monument, and how those ancient monuments have in turn shaped our expectation of the tourist experience today.

In modern times, hundreds of tourists and local Cairenes pose for thousands of photos at the Great Sphinx each day. The recent cult of the selfie has assured the iconic status of this human-headed lion, whose colossal profile is particularly suited to 'kissing' photos. This sort of interaction has been enabled and encouraged by the convenient modern viewing platforms flanking the Great Sphinx to north and south.

This has not always been the case. Until the mid-20th Century, the Sphinx was largely covered in sand. Visitors to Giza saw the colossal head sticking out of the sand, and recorded their impressions of its forlorn, sad nature – playing perfectly into the Romantic 19th Century image of picturesque vestiges of a lost civilization. Colossal royal statues in particular fit the narrative of the despotic, Oriental ruler undone, dethroned by the progress of History. As with Shelley's Ozymandias, 'nothing beside remains… lone and level sands stretch far away' from the Sphinx. As Mark Twain observed in 1869, the Sphinx is 'grand in its loneliness.' But the advent of photography meant that the Sphinx didn't remain alone for long.

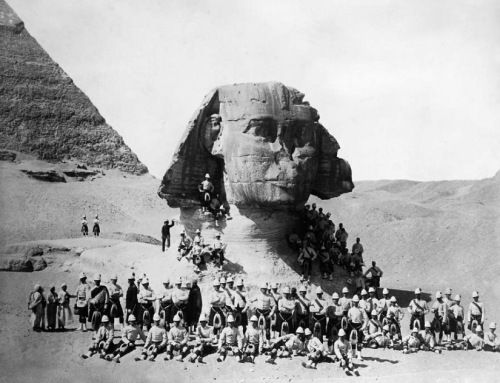

Of many similar images, perhaps the most resonant is this (above) from 1882 – the year Britain tightened its colonial grip on Egypt and the same year the Egypt Exploration Fund was founded. The British officers in full dress kilts and pith helmets, some with hands imperiously on hips, make clear the sense of entitled ownership of Egypt as an imperial possession.

Any photograph is, of course, not a neutral record of 'what happened' – especially in archaeology, as Christina Riggs has recently demonstrated for the Harry Burton Tutankhamun archive. These colonial set-pieces with the Sphinx have at their core the same highly constructed projections as any modern selfie. Photos of the Sphinx are also a useful index of the restoration work done to beautify – and ostensibly 'restore' – the sculpture for popular consumption. The Sphinx is prepared today for the mass tourist market, but only VIPs can actually get up close to it.

In contrast, surprisingly little is known about ancient perceptions of the Sphinx. Leaving aside the debate of who was actually responsible for its construction (Khafre is favoured by current Egyptological consensus, and who Discovery plump for in the doc), it may seem surprising that there is no Old Kingdom reference to it at all. Only in the New Kingdom (c. 1400 BC) do textual sources talk about the statue in terms of an identity – a divine identity – as 'Horus in the Horizon' (Horemakhet).

Although the term 'shesep ankh' (lit: 'living image') is often cited in Egyptological publications as the term for 'sphinx', in fact it rather appears (by the mid-18th Dynasty at least) that this was simply an epithet of the Pharaoh as a 'living image' of a god, usually the deity Atum. Ancient Egyptian terms for 'statue' are more nuanced than the space here allows (that'll have to wait until my book on Egyptian statues…) but it was really only the chance to spend time with Sphinx at Giza that brought these issues into focus for me.

Tuthmose III described as 'Living Image of Atum' at his Karnak 'Festival Hall'

In New Kingdom texts the Sphinx enclosure is referred to as 'setepet' (meaning 'most select/chosen place') and massive mudbrick walls would have restricted access to it, even views of it, perhaps only to the highest elite. This is in contrast to the assumption we may form based on the hordes of visitors the Sphinx receives nowadays and on apparent evidence of a Roman Period 'viewing platform'.

The quizzical (envious? outraged?) looks I received whilst poncing about on camera between the great paws of the Sphinx, brought home to me that access is rarely equal – even to as impressive a divine image as the great Sphinx. Did I have any more right to get up close to the Sphinx than the Egyptian school children on a day out?

The Discovery documentary (due to air Stateside late Summer) gives a rather televisual interpretation of the Sphinx as a 'Mythical Beast', but was an opportunity to feed in my own interpretations which – I hope – make the final edit. Perhaps instead of thinking of colossal royal statues in terms of bland 'propaganda', we should think in terms of the divisive nature of access (physical, ritual, intellectual) to them and how this shaped ancient and modern interactions with the past.

-- Sent from my Linux system.

No comments:

Post a Comment